|

Buddhist Spectrum

Venerable Professor Walpola Rahula Thera:

Pioneering western Buddhism

Rohan L Jayatilleke

We are indeed beholden to President Mahinda Rajapaksa and the

Minister of Posts Jeevan Kumaratunga for releasing a five-rupee stamp

with the photograph of Ven Professor Walpola Rahula and

internationalising his contributions for the propagation of Buddhism. In

1959, Venerable Professor Walpola Rahula published his book in England,

‘What the Buddha taught’ giving a lucid description of the teachings of

the Buddha in the 6th century BC. In a foreword to the book, Professor

Paul Demiville commented as follows”.

|

|

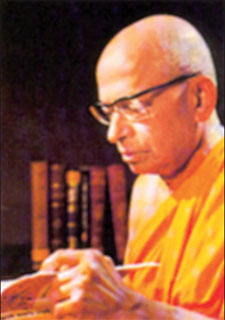

Ven

Professor Walpola Rahula Thera |

“Here is an exposition of Buddhism conceived in a resolutely modern

spirit by one of the most qualified and Enlightened representative of

that religion. The Dr. W. Rahula received the traditional training and

education of a Buddhist monk in Ceylon, and held eminent position in one

of the leading monastic institutes (Pirivena) in that island, where the

Law of the Buddha flourishes from the time of Asoka and has preserved

its vitality through the ages. The book (What the Buddha Taught is a

luminous account, within reach of everybody, of the fundamental

principles of the Buddhist doctrine, as they are found in the most

ancient texts. Dr. Rahula, who possesses an incomparable knowledge of

these texts, refers to them constantly and most exclusively. Their

authority is recognized unanimously by all Buddhists’ schools, which

were and are numerous, but none of which ever deviates from these texts,

except with the intention of better interpreting the spirit beyond the

letter.”

Scholarly acclaim

This acclaim of Dr. Rahula Thera and his book, from one of the very

few authentic Western scholars of Buddhism, optimized exactly the person

and qualifications needed for revolutionizing and giving integrity to

academic Buddhist studies in the West, wherein Christianity had evolved

the culture and the civilization, to be presented with what India

endowed the world with through the Buddha in the sixth century BC. This

work of Professor Rahula Thera gave a new perspective of Buddhism, as

learned in the Sri Lanka institutes of Buddhist studies. Thus there was

a revolutionary change into West towards Buddhism that arose India.

Professor Paul Demieile, further elaborating his perspectives on the

teaching of Buddhism to Western students, says, ‘As the first step in

charging the teaching and learning of Buddhism in American universities,

I required my students read Rahula's ‘What the Buddha Taught'. I also

gave a copy to my concerned and respected colleague who had hitherto had

perceived nothing profound in the Four Noble Truths. He commented to me

after reading Rahula's book, “Rahula introduced me to a Buddhism I have

never met before. You are quite right Christianity had better get

acquainted with Buddhism and you are quite justified in devoting your

own career as a scholar to the study of possible Buddhist – Christian

relations”. That colleague was Simeon E. Leland, the Dean who appointed

me to North Western university. I explained to him my professional

ambition to give integrity and academic excellence to the study of

Buddhism in American universities. He responded, “Let us teach Buddhism

at least to our own students”.

With Dean Laland's encouragement I set about second step in changing

to study of Buddhism in American universities. I read and read

Demilleville's Foreword, convinced and reconvinced that Rahula Thera

could raise the standard and change the character of Buddhist studies in

America. Inquiries to a few other scholars of Buddhism, in Asia as well

as on Europe, bolstered by ambition. Almost without exception because

“Dr. Rahula is a monk and not likely to accept a post in a Western

university”. But my advisors did not know how to measure my innocence

now the venerable's courage and insight into the far-reaching

implications of my project.”

In 1964 it became possible for Dean Leland to offer the Venerable Dr.

Rahula Thera an appointment at North Western University as the first

Bishop Charles Wesley Brashares Distinguished Visiting Professor of

Religion. Bishop Brashares had served for twelve years as Bishop of

Chicago area of the Methodist Church, one of the most influential

episcopates in Methodism.

When the Bishop retired, Methodisy Conference over which he preceded

established at North-western University a fund in his honour. The grace

of Bishop Brashares and the magnanimity of the Methodists in Chicago

area sufficed to stifle any sectarian opposition to the appointment of a

Buddhist as the first incumbent of a Chair established to honour a

Christian Bishop.

Bhikkhu Rahula, having satisfied himself by candid inquiry that his

appointment would cause no embarrassment to the Methodists and that he

would have unrestricted freedom to teach Buddhism in his accustomed

ways, accepted the Brashares Distinguished visiting Professorship for

1964-65. The revolution in teaching and studying Buddhism in American

universities began with the Fall Term, September 1964, when Bhikkhu

Walpola Rahula became the first Buddhist monk ever to hold a

professorship in a university in the West and began to meet his classes

at Northwestern University.

Phenomenal growth

This innovation set in motion by Ven. Dr. Walpola Rahula Thera was

commented upon by Professor Joseph Kitagawa writing in Encyclopaedia

Britannica's – Britannia Book of the Year 1965 (pp. 707-708) observing

the ‘phenomenal growth of scholarly interest in oriental studies in U.S.

Colleages and universities, blossomed in greater appreciation of the

art, culture and philosophy of Buddhism, which are inter-twined.

He wrote, the appointment of a Ceylonese monk, Walpola Rahula Thera

as the first Charles Wesley Brashares visiting professor, 1964-65 at

Northwestern University.

Professor Walpola Rahula's inaugural public lecture attracted an

international and an inter-religion audience with the Alice Millar

Chapel at Northwestern University overflowing. Two Methodist Bishops,

including Bishop Brashares and both the Ceylon Ambassador to the United

Nations, Sir Senerat Gunewardena and the Ceylon Ambassador to the United

States, M. F. De S. Jayaratna stood in the receiving line with Dr.

Venerable Rahula, Dean Leland and other University officials.

Other US based diplomats and hundreds of clergymen and laymen of

various religions joined students and faculty, filling the Chapel and

adjoing in rooms, to listen to a Buddhist monk lecture from a Christina

pulpit. The Buddhist Flag and the Lion Flag of Sri Lanka hung at full

mast before the Chapel's pulpit from which Professor delivered his

lecture, with Christian and American flags masted before the lectern on

the other side of the Chapel.

In his lecture Professor Rahula reviewed the contributions made by

Western religions and scholars that contributed to internationalize the

teachings of the Buddha.

He emphasized the study of Buddhism requires long years. Professor

Rahula had studied extensively the essays and articles written by

American socialists in languages of Buddhism and found their conclusions

were faulty.

In 1962 Grove Press issued the first paperback, the first American

edition of his ‘What the Buddha Taught’, which became a window to see

the Buddhism in its correct perspectives, as taught by the Buddha in

India in the 6th century BC for 45 long years, walking bare-footed any a

mile, what is now Bihar State and Uttar Pradesh of India. With the

growth of interest in Buddhism among American scholars, the Grove Press

in 1974 published Dr. Rahula's English translation of his Bhikkunge

Urumaya (Heritage of the Bhikkhu, New York Grove Press Inc). In this

work Dr. Rahula describes the history and the development of the

Bhikkhus’ response to his lay devotees and the inter-relations in the

matters of economy, politics, health, education and general social

welfare. This work gave the world a correct view of Buddhist, to the

West, as against works published by European, British and American

researchers.

Modern interpretations

Professor continued his studies on Buddhism in a most erudite manner

between the years 1950-1970. He prepared for publication for the first

time in history a translation into modern language of a pure Sanskrit

scripted a Mahayana Buddhism text, L'Ecole Francaise D'Extreme Orient

published this work. Le Compendium De La Super-Doctrine (Philosophie)

(Abhidharmasamuccaya) D. “Asanga.

This work appeared in 1971 as Volume LXXVIII and highly Learned

Series, Publications De L'Ecole Francaise D'Extreme-Orient.

This work was originally written by Asanga in the fourth century AD,

and in the eleventh some scholar translated it into French in the

eleventh century AD. In his introductory classes for undergraduates at

Northwestern University, Professor Rahula introduced his students

English translations of his Pali Canon, one full length book from each

of the three sections of the Tripitaka, (Sutta, Vinaya and Abhidharma):

The book of the Discipline Vol IV (from the Vinaya), Dialogues of the

Buddha Vol II (from the Sutta) and human types (From the Abhidharma).

Meditation in daily life:

Sabba Loke Anabhirata Sanna Part I

Dr Padmaka Silva

Earlier we spoke to you briefly about three meditations, Asubha

Sanna, Ahare Patikkula Sanna and Marana Sati. We spoke in simple

language about the manner in which they had to be practiced. Also we

indicated the merit, comfort and benefits of practicing those

meditations.

We thought of speaking about two other meditations. One is Sabba Loke

Anabhirata Sanna. The other is Sabba Sankharesu Anicca Sanna. Practicing

these two meditations is somewhat complicated. It is difficult to

establish the mind on these Sannas. Therefore we will explain two

methods of meditation which facilitate establishment of the mind on

these two Sanna meditations. By practicing these two meditations it is

possible to establish the mind on aforesaid two Sannas.

[SUBHEAD] No delight

The first one is Sabba Loke Anabhirata Sanna (perception about

generating the state of not taking delight in all worlds). “All worlds”

refer to eye, the objects seen by the eye, the ear, the sounds heard by

the ear, the nose, the odors smelt by the nose, the tongue, the tastes

felt by the tongue, the body, the contact felt by the body, the mind,

the thought objects felt by the mind (Sabba Sutta/ Loka Sutta – Sanyutta

Nikaya)

|

|

Develop a

liking for meditation |

Buddha himself has preached about the entire world. Therefore what we

have to do is to generate a state of not taking delight for the eye and

the visual objects seen with the eye, the ear and the sound………. etc.

Develop a state of not taking delight for the eye as well as the objects

visible to the eye. Develop an aversion. Develop a repugnance. Develop a

disgust. Is this easy or difficult?

We have a great liking for the eye as well as the objects visible to

the eye. We have a great liking, desire and attachment in respect of the

other sense organs ear, nose, tongue, body and mind also. It is due to

this attachment that we go to Sansara. We travelled in Sansara for a

long time because of this attachment to the sense organs. If we go to

Sansara again it will be due to this attachment. In order to get

liberated from Sansara, this attachment should be got rid of. One way of

getting rid of this attachment is developing a dislike. In order to

develop this dislike Buddha has instructed us to get used to the Sabba

Loke Anabhirata Sanna. It is difficult for us. It is really complex. But

if we take pains we can practice it.

Objects

Two methods can be adopted in this regard. While you are at leisure

develop a state of not taking delight for the eye and the objects

visible to the eye. That means do not consider the eye as a friend. Do

not consider the ear as a friend or a good thing. Do not accept the

other sense organs as friends.

We must willfully develop feelings of dislike. You can think of the

eye as an enemy or a torturer. Similarly with respect to the other sense

organs. Is it difficult or easy? It is difficult. Suppose Raga arises in

someone. Generally when Raga arises many people get excited. They either

get scared or get overcome by it. At such times you can think in this

manner. “Raga is an agony for us. It is a torment, a nuisance. The mind

burns due to that. How did this arise? It is due to an object seen with

the eye. A sound heard with the ear……….. The Raga was caused by them”.

You must be able to think in this manner when Raga arises. It cannot be

done at once. It can be done by a person who practices little by little.

We can think “This eye is not a friend for us. It has done no good for

us. It has done antagonistic things to us”.

To do this one has to remain in immense mindfulness. Can one think in

this manner with respect to eye, ear, nose…..? One cannot think in that

manner. Why can’t one think like that? One yields to raga or any other

phenomenon of torment. Through that one goes to Ayonisomanasikara. He

does not think of coming to Yonisomanasikara through that. When there is

a torment in the mind caused by Raga, Dosa or Moha it is possible to

take the mind to Yonisomanasikara based on that torment. One method of

generating Yonisomanasikara is the generation of a mind of animosity

towards those sense organs.

When Raga arises do not yield to it. Think “This large fire in the

mind arose due to an object seen with the eye. A sound heard ……..”. The

eye has not shown any loyalty to us. It has acted like an enemy. This

eye treats me in the way a tormentor does. Similarly the other sense

organs”. If one think in that manner it is possible to develop a mind

that dislikes the sense organs.

Accustomed

Practice it like a meditation. You can get used to this through the

meditation on sense organs. Is there anyone doing it? Are there people

not doing it? There may be people who are not doing it. But do it at

least from today. Through that one can get accustomed to this Sabba Loke

Anabhirata Sanna. This is complex. It may be impossible for an

individual to do it because it is complex. We have told you of a way of

overcoming that complexity and getting used to developing the mind

averse to eye, ear, nose, tongue……. At the same time practice as a

meditation (The meditation on sense organs). Based on both those facts

you will be able to establish the Sabba Loke Anabhirata Sanna in your

mind.

A time will come when you will be able to understand that you will be

able to develop the Samadhi based on that Sanna. It may not be possible

to do it at once. Therefore follow both methods. First method is (as

mentioned earlier) develop the dislike for eye, ear, nose, tongue and

body while you are seated, standing, walking or lying down. Think of

them as enemies, tormentors or entities that cause harm. At the same

time continue to practice the Ayatana Bhavana.

A time will come when you will be able to establish Sabba Loke

Anabhirata Sanna based on both these practices and develop Samadhi. It

will take some time. It does not happen in a hurry.

Therefore practice the Ayatana Bhavana well. Some may not be able to

practice the Ayatana Bhavana in full. It may be difficult. Therefore

practice it in brief. It may not be possible to do it in one stretch.

Therefore practice it even briefly at first. After that practice little

by little. As the mind gets used try to practice it in full. One who

does it with commitment without getting into a hurry will be able to

practice the meditation in full after some time. At the same time think

of developing the mind with the dislike for eye ear, nose, tongue, body

and mind.

(Compiled with instructions given by Ven Nawalapitiye Ariyawansa

Thera)

[email protected]

Buddhist concept of ethics

Prof Mahinda Palihawadana

The concept of ‘ Ahimsa ‘ had its origins in the movement to oppose

Animal Sacrifice initiated by the Buddha and Mahavira (also known as

Nigganta Natha Putta ) the founder of Jainism, in the 6th Century B.C.

During the time of the Buddha, many kinds of sacrifices were

practised by Brahmins who were the priests of the Vedic religion

professed by the upper castes of contemporary Indian society. The Buddha

did not see any value in these sacrifices, primarily because they were

entirely external rites. If one could speak of a ‘right sacrifice’, it

had to be something that was internal or ‘spiritual’.

Vedic pantheon

“I lay no wood, Brahmin, for fire on altars Only within burneth the

fire I kindle” – says the Buddha, mindful of the Brahmins’ practice of

tending a regular ‘sacred fire’ and pouring oblations into it for the

various gods of the Vedic pantheon.

This however was only a relatively harmless, albeit in the eyes of

the Buddha useless, activity.

|

|

Ethics

lighten our life |

The Vedic priests also advocated and performed several types of cruel

animal sacrifice such as “The sacrifices called the Horse, the Man, The

Peg-thrown Site, the Drink of Victory, The Bolt Withdrawn – and all the

mighty fuss- Where divers goats and sheep and kine are slain”.

The Buddha rejected all these sacrifices in no uncertain terms. For

example, when he was told of a ‘great sacrifice’ that the king of Kosala

was about to perform, where 2500 cattle, goats and rams were to be

immolated, he declared: “Never to such a rite as that repair The noble

seers who walk the perfect way.”

And, in one of the Jataka stories (Bhuridatta), the future Buddha is

reported to have said: “If he who kills is counted innocent, Let

Brahmins Brahmins kill.

We see no cattle asking to be slain that they a new and better life

may gain; Rather they go unwilling to their death And in vain struggles

yield their final breath.

To veil the post, the victim and the blow, The Brahmins let their

choicest rhetoric flow”.

Many times in his discourses the Buddha speaks of four kind of

persons – those who (1) torture themselves, (2) torture others, (3)

torture both self and others and (4) who do not torture themselves or

others.

Special interest

The first are the strict ascetics and the second the butchers,

trappers, fishers and robbers. It is however the third group that is of

special interest in our context.

It includes kings and powerful priests who, on such occasions as the

opening of a public building, hold a great ritual, “with the sacrifice

of many cattle, goats and rams, with wood-cutting and grass-strewing and

with much bullying and hustling of servants and slaves, working in fear

of chastisement.”

The Buddha does not approve of the conduct of these three classes. It

is the last kind, who do not torture themselves or others, that he

admires and they are none other than those who follow a compassionate

ethic such as the one the Buddha himself advocated.

A particularly touching discourse of the Buddha on animal sacrifice

comes in one of the most ancient Buddhist texts, the Sutta Nipata.

Here in a discourse on the ethical conduct fit for a Brahmin

(Brahmana-dhammika Sutta), the Buddha speaks respectfully of ancient

Brahmins who spurned the taking of life and never allowed their

religious rites to be tainted by the killing of animals. But corruption

set in and they started the practice of animal sacrifice.

When the knife was laid on the neck of cattle, the gods themselves

cried out in horror of that crime of ingratitude and insensitivity

perpetrated on an animal that was to humans such a faithful worker, such

a sustainer of life.

In the piece known as the Discourse with Kutadanta we come across a

king’s Brahmin counsellor who is preparing a great animal sacrifice,

concerning the right procedures of which he consults the wisdom of the

Buddha. T. W. Rhys Davids, the distinguished translator of this text,

alerts us to the fact that this would be the last thing that an eminent

Brahmin is likely to do – to seek the Buddha’s opinion on how to conduct

a sacrifice. So he describes the discourse as a “deliberate fiction full

of ironical humour”.

The Buddha tells Kutadanta of a worthy sacrifice held in ancient

times under the guidance of a certain enlightened Brahmin counsellor. In

this sacrifice no living thing is injured; all the labour is voluntary

and the sacrifice is offered not only on behalf of the king, but of all

the good.

Religious ethics

The Buddha then tells Kutadanta of even better forms of sacrifice. In

the course of this discourse, as C. A. F. Rhys Davids points out

(Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, article on Sacrifice/ Buddhist),

the stations in the road to the good life – the perfect lay life and the

perfect religious life – are set forth as so many degrees of sacrifice,

each better than the other. Thus the highest sacrifice is that insight

and wisdom which signifies the abandonment of the sense of self - i.e.,

the sacrifice of ego-centredness.

It is not a matter for surprise that the Buddhism along with Jainism,

the other great religion of Ahimsa, as well as several sects of

Hinduism, rejected animal sacrifice, although many other religions

approved of it to some extent or another.

The Buddha in fact was outspoken in His criticism of such entrenched

features of the contemporary religious and social scene as sacrificial

rituals and the caste system. (His ‘detachment’ was not indifference or

withdrawal of judgement, as has been often misunderstood. Consider his

reply to Potaliya who told him that the best person was one who neither

praised the praise-worthy nor blamed the blame-worthy: Far better is the

person who speaks in dispraise of the unworthy and in praise of the

worthy, saying in due time what is factual and truthful. (Anguttara ii

100)

In the modern world, there is a powerful movement which seeks to

reduce and eliminate the crimes that are perpetrated on animals and to

introduce to the social ethic an element of justice to other sentient

beings who share the planet with us, humans. This movement is all the

more remarkable in that it reflects an attitudinal shift in the

predominantly Christian West which is beginning to see the true nature

of the moral evil that the abuse and exploitation of animals is.

The fundamental thrust of this movement stems from the realisation

that animals are like us when it comes to suffering, pain and the

prospect of the deprivation of life. It is this very sympathy with the

suffering of animals and other sentient beings that is at the core of

Buddhist compassion or loving kindness (mettaa). Says a verse in the

Dhammapada, the most popular of Buddhist texts:

“All fear the rod of death are all scared.

(Understanding others) from one’s own example, One should neither

kill nor cause to kill.”

Simple terms

In the very next verse much the same is said with this addition: ‘For

all is life dear’. Here in simple terms is the ‘philosophy’ behind the

Buddhist ethic of Ahimsa: other living beings are like us; we should

treat them the way we want to be treated ourselves.

This is the spirit behind the first precept which enjoins us neither

to kill, nor to encourage killing as clearly explained in the Dhammika

Sutta.

This is the spirit that prompts the Noble Eightfold Path to forbid

the trade in flesh and engaging in fishing, hunting etc. for those who

profess to follow that Path. It is the same spirit that projected an

ideal of kingship in which the ruler provided defence and protection

(rakkhavarana-guttim) not only to the different classes of the human

population, but also to birds of the air and beasts of the land

(miga-pakkhisu).

The natural corollary of such a teaching in modern parlance is that

animals have the same right to life which we humans claim for ourselves.

And it is the sensitivity to this right that made Emperor Asoka, whose

life was abundantly inspired by the teachings of the Buddha, to

promulgate, in the well known Rock Edict I: “Here no animal shall be

killed or sacrificed”. This is an outstanding example of an ethical

teaching being made the basis for a legal pronouncement.

The tradition of royal decrees based on the ethic of respect for

animal life was also followed in Sri Lanka prior to the advent of

colonialism. Consider the Maaghaata (Do not kill) proclamations of five

kings of Lanka from the first to the eighth century, beginning with

Amandagamani Abhaya, which forbade the killing of any living being

within the realm. King Vijayabahu I in the 11th century and

Parakramabahu the Great in the 12th also made proclamations of

protection of wildlife and fishes in the forests and lakes of Sri Lanka.

Courtesy: The Buddhist Channel

|