Military regimes

A third world phenomenon:

Prof. Wiswa Warnapala Higher Education Minister

|

|

Idi Amin Dada

|

Military dictator and

President of Uganda from 1971 to 1979

Amin held the rank of Major

General and Commander of the Ugandan Army

Charges:human rights abuses,

political repression, ethnic persecution, extrajudicial

killings, nepotism, corruption and gross economic

mismanagement. |

|

|

General Sani Abacha

|

Nigerian military leader and

politician

The de facto President of

Nigeria from 1993 to 1998

Accused of human rights

abuses,controlling the press and inconsistent foreign policy

|

|

|

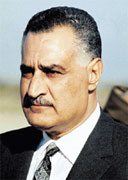

Gamal Abdel Nasser

|

The second President of

Egypt from 1954 until his death

Led the bloodless coup which

toppled the monarchy of King Farouk

|

The democratic politics in this country began with the introduction

of the adult suffrage in 1931, the consequences of which were many, and

the entry of Sarath Fonseka, who shed military garb a few weeks ago,

into active Presidential politics, has introduced a dangerous element

into the whole process of democratic politics in this country. It

portends a great danger for the very survival of democratic politics;

therefore the magnitude of the political danger needs to be analyzed

from the point of view of the experience of the military regimes which

were a third world phenomenon.

The Opposition, which is in disarray due to the absence of a

leadership capable of coming to terms with the Sri Lankan political

culture, wanted a military man to challenge the incumbent President and

the basis for his selection was the popularity which he commands as a

person who led the Armed Forces. This person, who was in a military garb

a fortnight ago, is now a candidate for the forthcoming Presidential

poll.

Executive Presidency

The Executive Presidency is an institution of Government with

enormous power, and the plenitude of power, which an Executive President

wields on the basis of the 1978 Constitution, is so enormous that the

holder of this office can eventually become an all-powerful dictator,

and this feature, with its plenitude of power, needs analysis in the

context of the emergence of Sarath Fonseka as the so-called common

candidate.

He says that he is an ordinary citizen, in the garb of an ordinary

politician but the fact remains that he donned a military uniform for

more than forty years and carried a gun. He, in my view, still remains a

man trained in the military tradition and derives inspiration from it.

He, because of his vast military experience in the last four decades, is

certain to get himself guided by those traits, and this has been the

experience in all regimes which came to be led by men in uniform.

It is at this point that I propose to examine the current political

scenario in Sri Lanka from the point of view of the experience of

military regimes in different part of Asia, Africa and Latin America.

All military leaders emerged on the basis of the slogan that their

services are required to restore democracy and good governance and

political stability; today Sarath Fonseka, wearing a white national

dress, is making similar rankings along with the entreaties of a divided

and disorganised opposition, which, apart from its common platform for

the purpose of promoting a common candidate, remain utterly confused and

divided.

The whole Opposition is a bundle of contradictions. A common front

cannot be constituted by an Opposition which remains divided on the

basis of ideas and strategies.

No democratic alternative could be built by the Opposition by

promoting a military man, and it is in this context that I would like to

quote C.E.M. Joad, according to whom ‘the life of the citizen of a

democracy is like the life of man, the individual, in the sense that its

successful conduct requires the constant exercise of vigilance and

initiative, the vigilance to ensure that the gains of the past are not

lost.” It is indeed inevitable, a necessity, that people of this country

need to exercise constant vigilance and initiative to prevent the

eventual emergence of a military dictatorship through the installation

of Sarath Fonseka into high office in Sri Lanka.

The military interventions, direct or indirect, have been a

phenomenon in many a third world country, and they became a form of

political intervention in most of the less developed countries (LDCs).

In these countries, in the first ten years after de-colonisation,

charismatic leaders who took over power as the first generation of

leaders in the post-independence period, were ousted by military leaders

in the name of democracy, good governance and stability. Stability and

continuity were treated as major slogans of the military aspirants to

high office. In Sri Lanka, a military leader is being promoted by a

civilian political leadership because of their absolute political

bankruptcy.

The nature of civil-military relations in the developing countries is

a special feature that needs discussion and elaboration as it impinges

on the role of the State in these countries.

In certain countries, there is an unique pattern of civilian control

of the military, whereas there are countries which have been ruled by

men in uniform. In Sri Lanka, the Army began as a small ceremonial Army

which has now been transformed into a professional Army with combat

experience and since independence the Armed Forces were under the

control of the civilian authorities.

Over-estimation

They were never given opportunities to penetrate into the civilian

affairs of the country and it was only in the context of the

humanitarian offensive against the LTTE that it got certain

opportunities to penetrate into certain segments of the civilian life.

Still it was under civilian control, and this is something unique for

Sri Lanka, and no attempt has been made to deviate from the historical

tradition.

The over-estimation of the contribution of the Armed Forces and the

unwanted publicity which the Armed Forces got in the aftermath of the

war created an unwanted impression that the Armed Forces have an

independent role, from which power-hungry and ambitious Sarath Fonseka

would have derived some inspiration. It, however cannot discount the

need for civilian control over the Armed Forces. A military man cannot

be allowed to assume high office as it portends a great danger for

democracy and Constitutional Government.

According to the classical theory in the West, the military is

neither expected or is it oriented to intervene in electoral or

representative democratic politics. It was this tradition of the West

which influenced the role of the Armed Forces in all the countries with

Westminster style of government.

Sri Lanka Army was nurtured in that tradition though an attempt was

made in 1962 to take over power. Most of the elements which were present

in the early sixties are present in the existing political scenario

where the same old forces have begun to play a conspiratorial role.

The common belief is that military emerges in the context of a weak

State, and this kind of analysis is based on praetorian model, according

to which military interventions are characteristically associated with

less developed countries which are described as ‘praetorian societies’.

In such societies, the characteristic feature is the ineffective

political leadership and the absence of instruments to channelise

political support.

|

|

Voting is a democratic right often

suppressed under military regime. AFP |

According to Samuel Huntington, who formulated the idea relating to

‘praetorian societies’, stated that such a regime is dominated by the

military or by a coalition of the military and the bureaucracy.

This happens in the context of a situation where the civilian

institutions are not strong enough to assert control over the Armed

Forces. In the weak states, there are opportunities for military

domination, and the only instrument available to them is force.

But everything depends on the political and social environment in the

given country. Huntington’s argument was that the rise of military

professionalism resulted in the military take-over of power, and this

thesis has been expanded in Huntington’s work titled ‘The Soldier and

the State.’ Both Huntington and Finer saw some relationship between the

military take-overs and the level of political development.

Praetorian society

Huntington’s analysis about the praetorian society was that its

civilian political institutions are always weak, and it was in this

environment that men in uniform take over power to achieve their own

ends.

This analysis was true in the context of military take-overs in

Africa, but the Latin American experience was linked to the level of

economic development. In most states, there is a casual link between

military interventions and the levels of economic development. There is

yet another argument; military groups exert considerable social and

political influence in a society - the reason for this kind of

development was the fact that military leadership came from the

privileged classes in the country, and this was the case in Sri Lanka

immediately after independence.

The 1962 coup leadership came from the upper strata of the Sri Lankan

society, and they, as a class, resisted the changes that came along with

the political change of 1956. They were largely committed to the

preservation of the old privileges and social relationships.

In other words, they were committed to defend the old social order.

In certain social situations, the Armed Forces largely because of

training and technical competence, maximise their power as patriotic

elements in society; this badge was attached to the Sri Lankan Army

after the demolition of the LTTE.

This, unknowingly, gave them opportunities to penetrate into the

civilian political life, and this I saw as a dangerous development from

which an ambitious man could emerge to taste political power. In this

context, the solution lies in the strength of our own political and

social institutions which still value non-military political secularism.

It would be interesting to examine the role of the Army in Asian and

African countries where they have set up military regimes. A military

dictatorship is a regime where the power resides with the military, and

it is a State directly under the rule of the military.

In the 1960s and 1970s, a large number of third world countries were

plagued with coups and counter-coups; in the subsequent decade there was

some kind of a reversal of this dangerous trend with which many a State

became ungovernable. Certain countries, despite this trend, alternated

between civilian and military regimes.

Military intervention became an important phenomenon in the third

world. It would be useful to import the Marxist analysis into our

discussion. Fredrich Engels once noted the divisive and independent role

of the Armed Forces within the State; he, in his work ‘Role of Force in

History’, stated that ‘in politics there are only two divisive forces;

the organised force of the State, the Army, and the unorganised,

spontaneous force of the popular masses’. This, in other words, meat

that an Army has a dual role.

The role of the Army in safeguarding internal security has grown

appreciably, and the Army in the developing countries realises its

supremacy over all other organisations.

For instance, in an economically backward country, an Army represent

the most significant, unique force, having an effective vertical

structure and social and cultural homogeneity. In the Asian and African

countries, the Army is not at all homogenous. In developing countries,

the Army can become a force promoting capitalist or non-capitalist

development and this depends, to a large extent, on the aims of the

given political leadership.

The Armed Forces took over power - in Egypt in 1952, Iraq in 1958 and

1963, Yemen 1962, Pakistan 1958, Burma 1962, Turkey 1960, Sudan 1958,

Nigeria 1966 and Syria 1961. All these countries, in the subsequent

years, alternated between civilian and military regimes.

Ruling elite

The conditions which motivate the Army to take over power varies from

country to country, depending on the nature and ability of its ruling

elite. The take-over of power by the Army is limited to the restoration

of order and stability in a society, and as Edward Shils says ‘military

men are neither businessmen nor civil servants striving for economic

development.’

In other words, their role is very limited and time bound. Without a

political organisation, no military regime can last long; it needs the

support of the masses.

If these factors are not available, they run the risk of taking the

inevitable path of self-destruction. Nowadays the military dictatorships

in the developing countries find it difficult to sustain themselves in

power as they have failed to address the urgent tasks facing these

countries. In certain cases, the military regimes have transformed

themselves into social regimes with mass political base. Still they find

it difficult to come to terms with internal contradictions within the

regimes. In most instances, they have failed to ensure speedy economic

development.

Professional corpraivism

In the early sixties a new wave of military coups took over power in

Latin America, and these regimes in this region resorted to Bonarpartism.

Such regimes were based on a kind of social demagogy. Yet another factor

was the professionalization of the Armed Forces and they, as a result,

began to have a say in various aspects of the State.

The use of Army men to perform civilian and administrative

responsibilities lead to professional corpraivism. In most cases, the

khaki - clad men try to settle the issues among contending politicians.

Mobutu in Congo came on the scene as a saviour in 1965. By 1984, 16

countries in Africa came under military rule; since 1963 coups in the

region averaged three per year.

Military was seen as an instrument of post-colonial governance in the

countries in Africa. Some regimes sought to acquire legitimacy by

presenting themselves as defenders of the nation against foreign

intrigue. There are ideological and stylistic differences between

military regimes, and this was the pattern in Africa. Most military

regimes tend to justify their military interventions on the ground that

their presence was necessary to clear up the mess left by the

politicians.

An excuse

This kind of agenda provided an excuse to military leaders to usurp

power. Many countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America experienced

variants of military regimes, and there is little evidence to support

the contention that military regimes have been more successful and

effective than the civilian counterparts.

In addition, they were responsible for the ‘failed States’ where the

economic record has been extremely poor. Yet another characteristic

feature was the personalisation of power, and this was seen in the

autocracies of Idi Amin, Sani Abacha and Gamal Abdel Nasser whose power

was based on a personality cult.

|