Trade and the Millennium Development Goals

Nike worker in Asia - Corporate Watch

Free trade economists argue that lower barriers to global trade

result in higher trade volumes, prosperous national economies and

poverty reduction. An alternative perspective observes that, in the

recent era of economic deregulation, trade has become the vector which

infects the world with the characteristics of laissez-faire capitalism.

Having no goal other than to replicate itself, trade lurches between

boom and bust, widening divisions between rich and poor countries.

Since 1995, when the current trade regime came into force, global

import duties ("tariffs") and other protectionist measures have fallen

to all-time lows and world trade has indeed grown handsomely at almost

10% pa. However, Africa's share of world merchandise exports has

steadily fallen to just 3% in 2006, inconsistent with a region

supporting over 10% of the world's population. Whilst China has been the

dynamo of trade liberalisation since admission to the World Trade

Organisation (WTO) in 2001, its booming economy has created only 13

million new jobs, small comfort for the 300 million underemployed in the

countryside. In India too, the status of economic tiger has resonance

only for the urban elites.

|

African leaders want the West to eliminate trade-distorting

practices in the agricultural sector. (Source: Internet) |

With similar patterns elsewhere is Asia, hundreds of millions of

rural people, more than the entire population of Africa, are fighting a

decline in food resources. With about 80% of Africans also dependent on

farm livelihoods, the number of people in the world classified as hungry

is rising, a statistic that indicts the world trade bonanza for

selectivity in its wealth creation and failure in agriculture.

In both continents this rural exclusion is also forcing radical

change in the traditional role of women in subsistence farming. In Asia

poor women from rural regions are migrating to the ubiquitous Export

Processing Zones (EPZs) where they dominate the production lines,

especially in electronics and light consumer goods. Working conditions

are vulnerable and largely without protection from the trade regulations

that stimulate the EPZs.

Poverty, hunger and gender issues underpin the Millennium Development

Goals (MDGs) and Goal 8 (Develop a Global Partnership) calls upon

countries to create a trading system which "includes a commitment to

good governance, development and poverty reduction". There is a

contradiction between the obligations of the Millennium Declaration and

WTO membership which the richer countries, as signatories to both, have

chosen to overlook.

Trade and Climate Change

A recognised characteristic of a low barrier trade regime is

migration of the world's manufacturing industry to a single country

offering low wages and modest environmental regulations. This role is

currently filled by China where low-skilled workers earn less than 5% of

their US counterparts. The relevance to global warming of this

displacement of production is two-fold; firstly the factory process is

likely to be less energy efficient and secondly the goods require

transportation over a much greater distance. Neither of these carbon

footprints is costed within the trading system whose avarice for low

wages ignores the impact on global warming.

Climate change will have its most immediate and severe impact on the

poorest countries. Through its contribution to global warming, world

trade therefore has an indirect as well as a direct impact on global

poverty. Dr Rajendra Pachauri, Chairman of the Intergovernmental Panel

on Climate Change, has expressed the view that a successor to the Kyoto

Protocol should take into account emissions from shipping.

The Roots of Trade Injustice

The roots of the injustice that plagues world trade in agriculture

lie in the aftermath of the Second World War. Self-sufficiency in food

production and the survival of traditional rural communities were high

on the agenda of European governments. Formation of the European

Economic Community (EEC), the predecessor of the European Union (EU),

led to the Common Agricultural Policy which since 1962 has offered

subsidies to farmers and guaranteed prices against the risk of volatile

markets.

Motives underlying the US Farm Bill, first introduced in 1949, were

identical and the methods very similar. To a greater degree than Europe

the profile of small family farms merged over the decades into large

units attracting the bulk of the subsidies. The associated business of

input chemicals, food processing and distribution also became

concentrated into very large corporations such as Cargill and Monsanto

which have been labelled as "agribusiness".

Although agriculture was included in world trading rules from 1995,

these farm support programmes in the EU and US survived the negotiations

of the "Uruguay Round" (1986-1994), a period in which developing

countries were poorly equipped to punch their weight. By 2006 the OECD

estimated that annual farm subsidies in developed countries totalled

$362 billion, more than half the GDP of Sub-Saharan Africa. Advocates of

the "liberalisation" of African agriculture should consult cotton

growers in Mali, sugar producers in Uganda or chicken farmers in Ghana -

whose livelihoods have been cut away by cheap produce available from

rich countries. These gargantuan subsidies in US and EU protect less

than 5% of the workforce whilst blocking development in the world's

poorest countries where 68% of livelihoods are derived from agriculture.

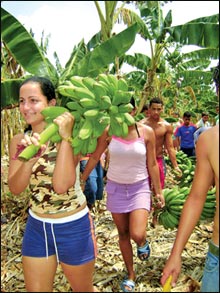

|

Cuban youth lend a hand in agriculture. (Source: Internet) |

In parallel to the stubborn inertia of these farm support programmes,

the era of deregulation of world markets and capital flows has enabled

agribusiness to extend its grip to the extent of owning about a third of

the world's productive land and controlling 75% of global farm trade.

Such industry concentration makes for inefficient markets and

inappropriate influence over policy areas such as trade regulations.

Trade and Poverty Reduction

The prime concerns today of most of the poorer developing countries -

food security and the protection of rural communities - are precisely

those that gave rise to the unfair competition they now face. Trade

rules need to replace the vision of more trade for its own sake with a

vision of countries whose people can first secure their basic needs of

food, health services and education. Such needs are enshrined in

international human rights law as well as the MDGs. The UN special

rapporteur on the right to food, Olivier De Schutter, has said that "the

subsidies in the developed countries are ruining the developing

countries' producers."

This is not to deny that radical reform in Africa is essential.

Investment is required not only in agriculture itself but also in the

infrastructure of transport and administration demanded by export

markets. Small-scale farmers and fisherfolk need help to compete with

multinational agri-business, for example in the formation of

cooperatives. "Aid for trade" could support these objectives alongside

international trade rules framed from a genuine development perspective.

Enlightened trade regulations might also have calmed the reaction to

the surge in food prices that occurred during 2008. Instead, most of the

countries struggling with food security have intensified a drive towards

self-sufficiency in food, backed where necessary with barriers to trade

in either direction. Such strategies run counter to the argument that,

facing the uncertain impact of climate change on water availability and

crop yields, global food production should be optimised through locating

crops in their most suitable growing environment, regardless of national

boundaries. Trade could make a vital contribution to food security if

only a more sensitive regime could be created.

Trade Rules

Unfortunately the world trading system has become so complex that it

is difficult to identify either the rules in force for a particular

country or those on offer under constant rounds of negotiations. And the

rules themselves frequently fail to achieve their intent. Moreover, if a

free trade philosophy is to work for poor countries then it must first

work for agriculture. The removal of EU and US farm subsidies is the

cornerstone for this ambition; all other intricacies of the rules are

minutiae by comparison.

Most of the world's poorest countries are now members of the WTO, but

they are also increasingly party to regional and bilateral trade

agreements which are allowed to override WTO rules. Additionally there

are preferential agreements designed to help poor countries, both inside

and outside the WTO structure, some of which are restricted to countries

classified by the UN as LDCs (Least Developed Countries). These various

concessions enable about 80% of LDC exports to enter developed countries

duty free. However, this percentage has barely changed since 1996 and

strategically critical duties tend to remain firmly in place.

There are also 79 African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries

which, as former colonies, have historic concessionary trading terms

with the EU. These ACP terms were ruled as discriminatory by the WTO in

2002 and the EU has offered replacement agreements known as Economic

Partnership Agreements (EPAs). Development agencies such as Oxfam have

argued vigorously that these EPAs will damage the development interests

of the ACP countries. As a result, negotiations have overrun the

original WTO deadline of 2007.

Out of this muddle one fundamental is clear - that the US and EU are

in no mood to concede ground on the core issue of farm subsidies.

Instead of offering unconditional phased removal of this structural

fault line, they are prepared to offer subsidy reductions only as

bargaining chips. They aim to leverage greater access to emerging

markets in developing countries, not just in manufacturing but also to

internal services such as utilities, health and education.

Apart from raising questions about the democratic right of poorer

countries to control their own industrial strategy (in line with the

established model of history), this bargaining approach threatens to

rebound on agriculture. Poor countries are allowed to nominate crops

regarded as crucial for internal food security and protect them with

tariffs against external competition and price volatility.

These "special products" and "special safeguard mechanisms" are

traded off in negotiations, creating especial difficulty for countries

such as India whose geographic territory embraces a wide variety of

critical food produce.

The Politics of Trade and Poverty

The political prospects of clearing this impasse in the interests of

the LDCs are not good. The richer countries are now focused more

intently on gaining access to markets in the successful developing

countries such as Brazil and Malaysia - who in turn seek access to

northern markets in agriculture.

These new middle income countries have been able to organise

themselves more effectively in WTO negotiations, the G20 group headed by

Brazil being the most important.

An LDC Group has also formed but tends to be excluded as talks reach

critical stages or deadlines, one of the reasons why the WTO is accused

of being undemocratic. Whereas in the past the G20 were natural allies

of the poorest countries, there is anxiety now that their export

strength is becoming as much a threat to LDC domestic markets as the

traditional colonial relationships.

Fair Trade

Mocking the dysfunctional Doha negotiations, Fair Trade is booming

amongst the consumers of 20 countries of northern Europe and North

America.

Products endorsed with the Fair Trade label guarantee that the grower

has been paid a price influenced by the cost of production rather than

volatile commodity markets; furthermore that farm workers are protected

by appropriate labour standards and that a premium has been paid to

contribute to community projects.

In 2006 Fair Trade reached about 7 million farmers and their families

in poor countries.

Fair Trade is constrained by its application to export products such

as coffee and bananas. It faces a range of criticisms, for example that

it is a selective subsidy for which the poorest farmers are unlikely to

qualify. And climate change issues have not yet been absorbed into the

Fair Trade model.

However such views miss the point that the buyer has started out with

a vision of dignity and rights for the seller. Fair Trade creates an

inspiring linkage between everyday consumers in wealthy countries,

global trade and the challenge of world poverty. |