|

A contemporary Jane Austen?:

'To thee belongs THE rural reign'

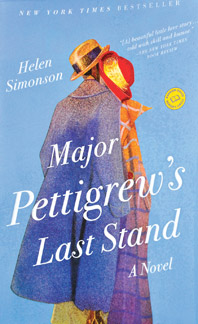

Helen Simonson is not one of the established greats. She is a

middle-aged Anglo-American author, a Britisher settled in the USA, and

'Major Pettigrew's Last Stand' (2010) is her first novel. Not that a

first novel cannot be great - consider 'Wuthering Heights', Emily

Bronte's first and only novel,written at the age of thirty, one of the

greatest novels ever written. My purpose in featuring 'Pettigrew' here,

however, is to try to illustrate the assessment of a contemporary work

of fiction from the perspective of the Imagination. Helen Simonson is not one of the established greats. She is a

middle-aged Anglo-American author, a Britisher settled in the USA, and

'Major Pettigrew's Last Stand' (2010) is her first novel. Not that a

first novel cannot be great - consider 'Wuthering Heights', Emily

Bronte's first and only novel,written at the age of thirty, one of the

greatest novels ever written. My purpose in featuring 'Pettigrew' here,

however, is to try to illustrate the assessment of a contemporary work

of fiction from the perspective of the Imagination.

Simonson has an unaffectedly pleasant and comfortable style. It is a

third person narrative, as in Jane Austen, written mainly from the

viewpoint of the protagonist, Major Pettigrew, a widowed retired army

major in his late sixties resident in a pretty little village in

southern England. From the outset Simonson proves herself a master of

context, one of the primary requirements of a good novel. She captures

the atmosphere of modern English village life not only through her

evocative descriptions of the landscape and the domestic and other

locations of the action, but through dialogue that skilfully develops

the social fabric. This contributes greatly to the readability of the

book apart from the absorbing story, that other sine qua non of

full-length fiction. Here is a synopsis:

|

|

Helen

Simonson |

Major Pettigrew is shocked by the news of his brother's death. His

thoughts turn to the pair of ornamental guns gifted by a Maharajah to

his father, who had been a Colonel in British India. One gun had been

left to each of the brothers on the understanding that upon the death of

the one the other would take over his gun so that the pair could be

passed on down the generations. Pettigrew develops an interest in Mrs

Ali, the widowed middle-aged Pakistani lady who runs the village

grocery. They begin to meet to foster a shared interest in reading. This

earns him the disapproval of the golf club fraternity as well as of his

son, a London-based yuppy who is engaged to a brash young American

woman. The major learns with dismay of his son's complicity with his

brother's widow and daughter in a plan to sell off both the guns as they

are worth a fortune.

Mrs Ali herself is at a crossroads. She is independent but, being

childless, obliged by tradition to hand over the shop to her late

husband's nephew and retire within the bosom of the latter's family who

are also settled in England. She decides to comply on the condition that

the nephew marries the Pakistani girl with whom he has had an illicit

affair and fathered a son. The family had demanded that he renounce the

girl and the child as the penalty for violating the moral code. He had

yielded to the pressure although still in love with the girl. Meanwhile

the major acquires temporary possession of his brother's gun in order to

restore it, and determines to show the pair off at shooting parties

organised by the lord of the local manor.

Things come to a head at the annual golf club dinner-dance. The lady

members decide to feature an Indian theme with a re-enactment of

Pettigrew's father receiving the brace of guns as a token of the

Maharajah's gratitude for his having protected the Maharani when a

trainload of passengers was massacred during Partition. The Major takes

Mrs Ali along as his guest. Things turn ugly during the enactment when

the aged father of the Pakistani caterer proclaims that his people have

been insulted by the proceedings. In the ensuing uproar Mrs Ali leaves

on her own while the Major stays on to participate in the resumed

encomium for his father.

Pettigrew resigns himself to the loss of Mrs Ali. However, in the

course of a journey to Scotland to join a shooting party, he detours on

the impulse to look her up at her family home. He finds himself in the

midst of a family dispute over Mrs Ali's insistence that the nephew

marry the girl he had been forced to renounce and accept his son. On

realising that Mrs Ali still loves him he persuades her to leave with

him and they spend an idyllic weekend in Wales, the shooting party

forgotten. When they return to the village on the eve of the nephew's

wedding, the latter's grandmother attacks and seriously injures the

bride. The nephew runs away to commit suicide by flinging himself off a

precipice into the sea. The Major intervenes, saves the nephew but falls

halfway down the cliff himself and has to be rescued. The grandmother is

arrested for deportation, the major recovers in hospital having earned

the admiration of all concerned, including his son who breaks the news

that the one gun used by the major in the scuffle had fallen down the

cliff and been destroyed. The nephew is reconciled with his family

although the girl decides against marrying him, valuing her independence

too much. Finally Pettigrew and Mrs Ali are married in the presence of

friends and well-wishers along with some ill-wishers among the ladies.

Simonson adroitly captures the realities of modern English village

life, with the complicating Asian immigrant presence, the natural beauty

of the countryside threatened by a massive housing project as well as

the destruction of wildlife by shooting parties, the solidarity among

the local gentry as centred on the golf club and the pernicious

commercial influence of London and the USA.

It is good social satire facilitated by a love story that involves a

seemingly unmatched couple and provokes the exposure of racialism,

materialism and extremism. As a convincing slice of life presented with

humor and understanding and a story illustrating the triumph of love

over prejudice, the novel is surely good value for money - USD 25.00 to

be precise. It is good social satire facilitated by a love story that involves a

seemingly unmatched couple and provokes the exposure of racialism,

materialism and extremism. As a convincing slice of life presented with

humor and understanding and a story illustrating the triumph of love

over prejudice, the novel is surely good value for money - USD 25.00 to

be precise.

It has been suggested that Simonson is a modern-day Jane Austen,

working within the small compass of contemporary English rural society.

On the face of it this seems a fair comparison. But Austen's achievement

has to do with the revelation and adjustment of character through

developing personal relationships.

In the process our own understanding of human nature, our own and

other people's, is adjusted and deepened. Thus genuine value is created

for us as Austen, even within that small compass, puts her heart into

making sense of the full extent of her experience of life. In

'Pettigrew' we have the major convincingly drawn by the author. He is a

loyal subject of the crown, the ideal English gentleman and sportsman,

having his foibles and prejudices but ultimately humane, liberal and

enlightened. He is challenged by the social realities of modern life but

is able, through his eminently civilized response, to come to terms with

them. But he is the only three dimensional character in the novel. The

others are two dimensional or less, even Mrs Ali however sympathetically

she is drawn. They are simply foils to the major, eventually won over by

his gallantry, decency and magnanimity.

What we realise from this one-sided character focus is that 'Major

Pettigrew actually makes his last stand' as the latter-day

representative of the British Raj. He is valiantly discharging the

'white man's (residual) burden' of civilizing the benighted of the third

world and chastening his prejudice-ridden countrymen including his son.

Of course there has to be a grand gesture, so he romances the least

objectionable or most British-like of the immigrants, the eminently

presentable Mrs Ali. She speaks as good English as the major and,

significantly, shares his love of Kipling, the writer who unreservedly

romanticised British imperialism. (Jane Austen's heroines, on the other

hand, were partial to Scott, the romantic, and Byron, the rebel - no

upholders of the status quo.)

And it is ultimately the status quo that this novel celebrates. Which

is why there is no genuine creation of value as we would expect of a

work of the imagination.

The author has set herself to paint a portrait of the modern English

village and developed an ingenious tale to frame it. But she does not

appear to have responded fully to the potential of the experience she

records. That is why the other characters are thinly realised and the

events are somewhat sensationalised, viz. a dinner-dance fracas,

attempted murder and suicide and a heroic rescue.

Thus, in spite of the effort to portray the major as a conquering

hero, romantically and otherwise, we see him for what he actually is,

what Lawrence would call a social being, a somewhat superior

representative of his social class and little more.

And, as in 'Downton Abbey', it is under the benevolent umbrella of

such a favoured class that the lower orders of rural society must

necessarily, it seems, find shelter. Britannia may no longer rule the

waves, but the evidence of this novel is, in the words of Thomson's

poem, that still "to thee belongs the rural reign."

|