|

The imagination beyond poetry:

‘We work in the dark, we give what we have’

We have considered the vital role that the imagination plays in the

production of great poetry, whether of the figurative or plain-speaking

type. We remember, however, MI Kuruvilla's assertion that Coleridge's

definition of the creative imagination is the foundation, the

cornerstone, of modern literary criticism. That being the case, its role

should be apparent in the production and the assessment of the other

areas of creative writing, namely drama and fiction. Let us see how the

imagination makes its presence felt here. We have considered the vital role that the imagination plays in the

production of great poetry, whether of the figurative or plain-speaking

type. We remember, however, MI Kuruvilla's assertion that Coleridge's

definition of the creative imagination is the foundation, the

cornerstone, of modern literary criticism. That being the case, its role

should be apparent in the production and the assessment of the other

areas of creative writing, namely drama and fiction. Let us see how the

imagination makes its presence felt here.

Consider Coleridge's point that the poet “brings the whole soul of

man into activity”; and Eliot's complementary point that the “poet's

mind...is constantly amalgamating disparate experiences”. This means

that the writer has to respond from the many-faceted totality of his

being to the many-faceted totality of his experience. Only then can the

imagination perform its “esemplastic” role of creating unity out of

diversity.

Thus, the dramatist and the novelist must, like the poet, write from

“the foul rag- and- bone shop of the heart” as Yeats puts it, and with

his “eye glancing from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven” as

Shakespeare says. And this is what Henry James implies in his

impassioned explanation of the role of the writer in his short story,

'The Middle Years': “We work in the dark, we give what we have, we do

what we can. Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. The

rest is the madness of art.”

Deep calling

“The dark” refers to the dark place of the heart, the man or woman

one is inside, the real you comprising thoughts and feelings, attitudes

and passions, ideas and emotions. The imaginative writer gives his or

her all from this centre. Only then does the imagination rather than

just the fancy come into play and enable the writer to communicate

effectively to the heart of the reader - a case of deep calling unto

deep.

|

|

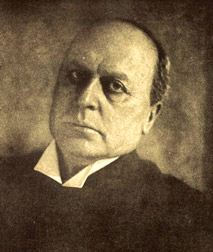

Henry James |

If the dramatist or novelist as much as the poet is successful in

doing this he affects our vision of life and adjusts our system of

values. In the process he creates value for us, a phrase better known in

business circles but that should be taken more to heart in the literary

context. We know that a work of art has been produced through the agency

of the imagination rather than the fancy when we realise that it has

created such value for us.

Let's take a work each of drama and fiction, 'Hamlet' and

'Persuasion', We have already considered these two works separately and

extensively, so they will serve as convenient illustrations of the

influence of the imagination on the author and its effect on the reader.

Shakespeare's 'Hamlet' enables us to comprehend the emotional burden

of one who finds himself faced with a challenge so complex and great

that it renders him powerless to act. It is also the dilemma of one

caught in the vice of seeing and being. The extent to which he sees into

reality robs him of the impulse to be himself since he could only do so

by compromising that perception. But to remain thus and condone the

'rottenness' of the status quo is unacceptable to the man of integrity.

Ultimately he sees his way to right action, 'rightly to be great.' This

exposes one to great risk, but it must be taken if one is to find peace.

'The readiness is all...there is a special providence in the fall of a

sparrow.'

Through his imaginative handling of plot, character and language

Shakespeare enables us to empathise with Hamlet and realise the

relevance of his plight to ourselves. The man of sensibility invariably

agonises about how to confront a cynical world. But confront it he must

to maintain his integrity, and when he does so with a refined conscience

he finds peace, even if at personal cost. That is a moral too valuable

to be missed, which is why the dying Hamlet tells Horatio-and us too: ,

“Absent thee from felicity awhile, And in this harsh world draw thy

breath in pain, To tell my story.”

In 'Persuasion', as Shakespeare does with Hamlet, Jane Austen makes

the consciousness of Anne Elliott real to us. Because the author avoids

sentimentality and maintains an objective though sympathetic approach to

her subject, she succeeds in projecting her heroine as a credibly

complex character. We therefore readily empathise with her sense of

loneliness and neglect and her longing for love. We also admire her

fidelity and devotion and generosity of spirit. All this comes out

through the skilfully realised context of situations and interrelations

to which Anne's consciousness is exposed. It is also through this

context that Jane Austen demonstrates how unfavourably the values and

achievements of a parasitical social class compare with those of a more

energetic and self-sufficient class lower down in the class system.

Consequently the novel effectively alters our view of the

involuntarily unmarried woman and of class consciousness. In the process

we realise that the pain of being and feeling unloved need not result in

bitterness and self-pity but, bravely endured, produces sterling

qualities of character like patience, fortitude, loyalty and the

capacity for selfless service. And that ultimately the best way to cope

with the lack of love is to show loving consideration for others, which

brings its own rewards. This is a theme dealt with even more forcibly

and, unlike here, tragically in Francois Mauriac's 'Therese'.

Symbolic significance

What we have seen in these two works is that the imagination, when it

is at work in a dramatic or fictional work, creates value for us in two

key ways. First, the treatment of the subject is so concretely realised

that, in its very particularity, it has a symbolic significance. It is

more than 'the cry of its occasion', it comes to stand for something far

beyond its actual context. Despite their characters and places and

events having 'a local habitation and a name', the writers have captured

the 'things unseen' that are universally applicable. Thus we see how the

imagination reconciles, as Coleridge claims, 'the general with the

concrete, the idea with the image, the individual with the

representative.'

Secondly, there is the moral dimension of a truly imaginative work of

drama or fiction. We are affected morally in the sense that the works,

whether their endings are tragic as in 'Hamlet' or happy as in

'Persuasion', are ultimately life-affirming and life-enriching. As such,

they motivate us towards a greater commitment to life and a greater

sense of our connection to what Hawthorn spoke of as 'the magnetic chain

of humanity.' Lawrence said that 'the business of art is to reveal the

relation between man and his circumambient universe, at the living

moment.' For him this is what constitutes the essential morality of a

work of art. And it is the imagination that works to makes this

'relation' live for us; and makes us want to strengthen it by taking the

value it has created for us to our bosom, making it our own.

Coloured imagination

Wordsworth was closely associated with Coleridge, and in his preface

to their joint production of 'Lyrical Ballads', he modestly referred to

the objective of his poetry as follows: “..to choose incidents and

situations from common life....and to throw over them a certain

colouring of imagination, whereby ordinary things should be presented to

the mind in an unusual aspect.' What we have seen in the two works we

have considered is that the imagination has coloured them, not

superficially but powerfully from within, to the extent that they have

presented an 'unusual' symbolic and moral aspect to our minds. Thus has

Shakespeare reworked the old revenge theme and Jane Austen the

conventional romantic theme to turn them into something rich and

strange, universal and eternal.

So the ultimate test as to whether a work of fiction or drama is a

work of the imagination is the extent to which it creates value for us.

If it does so, as we have seen in these two works it can, we know that

the writer has responded to the totality of his experience with the

totality of his being. And since he has thus 'worked in the dark, giving

what he has and doing what he can' through technique and style,

characterisation and plot etc., the power of the imagination has taken

over and 'the madness of art' has done the rest for him.

|