Issues related to solid waste management in Sri Lanka

Prof. Niranjanie RATNAYAKE

‘Waste’ as we all know, is what we have no use for – maybe we have

used it and it is not suitable for further use, or the useful material

came with some useless material that has to be discarded, or perhaps we

have an excess supply that we cannot use, or return to the supplier, and

therefore has to be thrown away. Anyway, we throw them away because we

feel that we have no further use for them.

|

There are many reasons for the enormous increase in

waste quantities |

Many things have changed in the world within the last 50 years or so.

In the 60’s and 70’s, USA was called ‘the throwaway society’, while our

lifestyles were much more sustainable. We wore cotton clothes (which

were biodegradable), and our eating habits were such that food was

hardly wasted, and always there were domestic cats and dogs that were

fed on table scrap – unlike the pets of today that have to be fed

special foods from cans. There were no plastic shopping bags or lunch

sheets – there were brown paper bags that could carry a decent weight,

and carrying a bag when you go marketing was the ‘done thing.’ Food was

wrapped in plantain leaves or carried in reusable containers or between

two plates, (often metal). ‘Take away’ food was a rarity. You had to go

and eat at a restaurant or hotel, where cutlery, crockery and all other

utensils were reusable. There were no fancy names like ‘3-R principle’,

but ‘Reduce, Reuse and Recycle’ were the ‘common sense’.

Bottles were almost entirely glass, and was never thrown away because

the ‘Bottle-paper man’ was a regular visitor, and aerated water and

liquor bottles were not sold without an empty bottle or a thumping

deposit – which itself was a deterrent.

Newspapers went for wrapping all kinds of goods at the grocer’s and

used exercise books were destined to go to the gram sellers for the

‘kadala gottas’. Metals like cast iron and aluminium were collected from

door to door for recycling, coconut shells were used as firewood or for

ironing, and even coconut residue either had uses like for floor

cleaning or could be sold after sun drying, as a raw material for oil

production. Almost everyone had a small plot of land, where you could

have a small pit for the garden waste and any other stuff that needed to

be thrown away and since most of it was biodegradable, the pit seemed to

last forever.

|

The average composition of waste in the municipal areas |

As far as I know, the solid waste collection and disposal was only

happening in the few Municipal Councils, and the simple lifestyle of the

majority of the people resulted in quite manageable quantities to be

collected, and incineration was practiced - perhaps not the best choice

of technology even those days when oil prices were not high – but we did

not see heaps of garbage lying around. So basically, we were living by

the 3-R principle, without calling it that. A fine example of this is

found in the Buddhist teachings, ‘Vinaya Pitaka’, where I understand

that the Buddhist priests have been advised to reuse the good parts of

the robes as undergarments when they were too old to be worn as outer

wear, and then used as bed linen, and then as towels or napkins, door

mats and finally when it is no longer useable as a cloth, to mix it with

clay and use as a filler material for the walls.

Changes

Unfortunately, that era is now gone, and we in Sri Lanka have got

caught up in the Winds of Change, and have become a ‘throwaway society’

in a big way.Our opportunities for reuse are masked by the availability

of so many consumer items,so that the temptation is to purchase

something new rather than reuse an old thing as a substitute. Mostly due

to lack of storage space, we prefer to throw away things regardless of

the possibility of reuse, and purchase again when we need it next time.

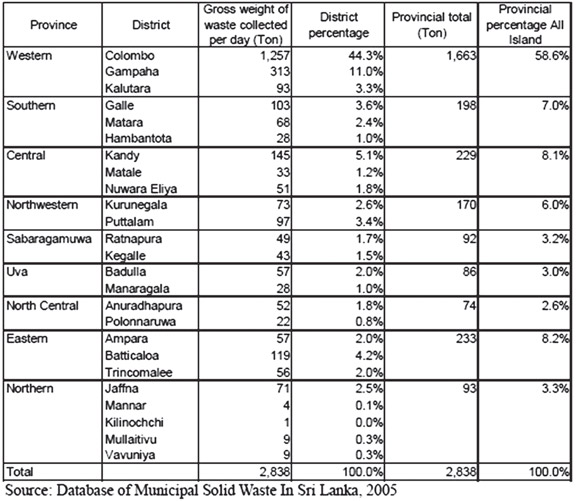

This is apparent when we look at the solid waste generation

statistics in the recent past.This table from the JICA Report of 2007,

shows the amounts of solid waste collected by the local authorities in

the 9 Provinces of Sri Lanka. This shows that 1663 tons of waste is

collected (nearly 60% of the total waste) per day in the Western

Province, and out of that 1257 tons per day (44% of the total) is

generated in the Colombo District.

Waste management

So we can see that our first issue is the sheer quantity of waste

generated, that needs to be managed. There are many reasons for this

enormous increase in

|

Plastic soda bottle lamp |

waste quantities, such as the population increase, urbanization and

migration of population from the rural to the urban areas leading to

much higher population densities , changes in lifestyle, and economic

activities etc. A study carried out by Bandara et al (2007) in Sri Lanka

has shown that the per capita waste generation rate is directly related

to the social status of the people.

The second issue is the change in characteristics of the waste

generated.Changes in lifestyle, introduction of cheap plastic and

polythene items such as disposable tableware, takeaway foods in

polystyrene packing and polythene lunch sheets, household electronic

items and computers, higher level of sophistication in clothing and

households leading to use of more chemical cleaners and laundry products

in plastic cans, aerosols etc., replacement of glass bottles with

plastic containers thatare not reusable, etc., have resulted in a change

in composition of the waste, with approximately 10% of the weight being

now contributed by plastics.

The average composition of waste in the municipal areas is shown in

the pie chart. There are slight variations in the composition among the

Municipal Councils and the hierarchy of local authorities, the

percentage of short term biodegradables increasing and the long term

biodegradables reducing as the level of the local Authority increases

for the Pradeshiya Sabhas, through Urban Councils to Municipal

Councils.However, in all local authorities, the major portion of waste

(40% – 66%) is short term biodegradable, as seen in the Figures below.

Even though the composition of waste shows that the major portion of

waste is short term biodegradables, giving a weight ratio of about 8

times that of plastics and polythene, with the lower density of

polythene compared to the biodegradables (A study done by Ontario Waste

Diversion Organization (2001) showed that the density ratio is about 1:

30), reverses the volume ratios to nearly 4 times plastics and

polythenes to that of biodegradables. In addition, the lower density

makes the loose plastics rise to the top when dumped, and since often

the other garbage is covered with plastic bags, we see it at the

surface.

|

PET bottles being used as lampshades |

Our next set of issues comes from what happens to the waste if we

just allow it to remain in the environment. Unfortunately, this is what

we seem to have been doing in the past, except for a few sporadic

attempts at treatment by composting and incineration. Garbage dumped by

the roadside, water bodies and in low-lying areas became a common

sight.So what are the issues related to this poor management of solid

waste?

* Obviously, it degrades the aesthetic value of the environment, and

along with it socio-economic issues such as lowering of land values,

increase in informal

sector employment like rag-picking and scavenging and related

activities

* Health issues due to the breeding of stray cats, dogs, rats and

other vermin,mosquitoes

* Effects on wild animals that are attracted to these waste dumps,

like deer,bandicoots, and even elephants, which may cause death (due to

suffocation or consumption of plastics and toxic substances) as well as

whose feeding habits change causing changes to their immune systems and

other vital processes that may even lead to irreversible changes.

* Air pollution due to the anaerobic degradation of the biodegradable

portion resulting in emission of air pollutants like methane, ammonia,

hydrogen sulphide and other offensive gases

* Surface and ground water pollution from the leachate that seeps

through the ground or is washed off with the surface runoff during wet

weather.

* Increase in Global Warming potential due to the emission of green

house gases such as CO2, CH4 and nitrous oxide. The contribution to the

greenhouse gas budget of Sri Lanka associated with the methane released

into the atmosphere from MSW open dumps has been found to be significant

(Ramya Kumari & Bandara, 2004).

So why have we allowed our environment to be so degraded by solid

waste, and let the solid waste management issues reach such huge

proportions? Is it ignorance of the consequences? I don’t think so.

Perhaps some of the consequences like contribution to global warming

and ground and surface water pollution due to leachate may not be

obvious, and needed research and access to information beyond the common

man’s reach, but the aesthetic effects are so obvious that any person

should be able to see the effects.

Technology

There are high tech solutions, but there are many low tech solutions

too, particularly to manage at the source, so that only the portion that

we really cannot handle at source is collected for disposal.

Policies, laws and standards

The legal framework for solid waste management is quite well

established in the country. According to the Local Government Act, the

Local Authorities in Sri Lanka are responsible for collecting and

disposal of waste generated by the people within their territories. The

necessary provisions are given under the sections 129, 130 and 131 of

the Municipal Council Ordinance; the sections 118, 119 and 120 of the

Urban Council Ordinance; and sections 93 and 94 of the Pradeshiya Sabha

Act. Provincial Councils have been given the powers to manage solid

waste, as a devolved subject under the 13th Amendment to the

Constitution of Sri Lanka.

National Environmental Act

The

National Environmental Act (NEA) of 1980 which was subsequently amended

in 1988 provides the necessary legislative framework for environmental

protection in the country. The Ministry of Environment prepared the

National Strategy for Solid Waste Management in 2000, which recognized

the need for SWM from generation to final disposal through a range of

strategies, based on the 3-R principal, as well as the need for

decentralized actions as well as centralized actions such as developing

the market conditions for sale of recyclable materials and products made

from recycled materials. The

National Environmental Act (NEA) of 1980 which was subsequently amended

in 1988 provides the necessary legislative framework for environmental

protection in the country. The Ministry of Environment prepared the

National Strategy for Solid Waste Management in 2000, which recognized

the need for SWM from generation to final disposal through a range of

strategies, based on the 3-R principal, as well as the need for

decentralized actions as well as centralized actions such as developing

the market conditions for sale of recyclable materials and products made

from recycled materials.

This was superseded by a National Policy for Solid Waste Management

prepared in 2007 “to ensure integrated, economically feasible and

environmentally sound solid waste management practices for the country

at national, provincial and Local Authority level”. A major activity

that sprung from the National Policy is the setting up of the Pilisaru

Programme in 2008, to solve the solid waste problem at the national

level, with

the help of the “Pilisaru Project” at the Central Environmental

Authority, with the concept of reusing the resources available in the

collected garbage to the maximum before final disposal. While technical

and financial assistance on SWM to the local authorities is a major role

of Pilisaru, it is also empowered to take legal action against those

local Authorities that are not managing their solid waste properly.

In addition, a general guideline for the implementation of SWM was

prepared by the Central Environmental Authority in 2005, which is

available in the CEA website. The Central Environmental Authority has

stipulated regulations giving standards and criteria for generation,

collection, transport, storage, recovery, recycling, disposal or

establishment of any site or facility for the disposal of any waste

specified as ‘Scheduled Waste’, and such activities need an EPL for

operation. (Government Gazette Extraordinary No. 1534/18 - FEBRUARY 01,

2008). A specification for Compost from Municipal Solid Waste Management

and Agricultural Waste was stipulated by the Sri Lanka Standards

Institution as Sri Lanka Standard 1246: 2003 (UDC 628.477.4).

Thus we can see that lack of policies or legal provisions cannot be

cited as a major barrier for a clean and healthy environment free from

garbage dumps. Lack of funding is a factor, because the legal

responsibility of solid waste management is with the local Authorities

and the Provincial Councils, which are not profit making organizations.

Most of the local Authorities pay more attention to the improvement of

physical infrastructure coming within their purview, and their concern

toward SWM issue is low and the amount of resources utilized for SWM is

relatively low. However, within the last few years, several funding

agencies have provided financial assistance to the Ministries of

Environment, Local Government and Provincial Councils, for Solid Waste

Management

Attitude

However, I think the main reason behind the poor state of affairs

with regard to our Solid Waste Management is our attitude. We are so

used to not taking responsibility for the waste that we produce, that it

is very easy to blame the Local Authorities for not doing their job, and

absolve ourselves from the blame. If we stop for a moment to think ‘who

is actually responsible, any reasonable person would realize that we,

who produce the waste, should be held responsible for safe disposal of

it too. True enough, we are paying taxes and the local authorities are

expected to provide services, but when it comes to resource wastage, how

much can money compensate? All these heaps and mountains of garbage

contain so much of resources that should not have gone there in the

first place. This is what we should be thinking about. Not throwing good

stuff away and then trying to recover some resources from it, but not

throwing it away at all.

How can we change this?

Ideally, if we could go back to the lifestyle that we had 50 years

ago, we would be undoubtedly much better as far as sustainability goes.

However, that is unlikely to happen; but we can still keep our hopes for

a better future, because the younger generation seem to be more

conscious about the diminishing resources than ours. If we can even at

this late stage provide them with the right kind of platform, we may be

able to redeem our losses, at least to a certain extent.

Most of us are familiar with the hierarchy of actions in Solid Waste

Management.

Avoid – Do you really need it?

Reduce – How much is enough?

Reuse – Can it be used for another purpose?

Recover – At least some parts, metals, chemicals

Recycle – Don’t waste your waste – convert to usable products or

energy

Dispose safely

How can we practise these principles? We need to inculcate them in

our society. Make them our lifestyle. We have to be innovative, and

think outside the box. We Sri Lankans are quite good at improvisation

and innovations. We can see that things are moving in the right

direction, with the support of the Ministries of Environment and Local

Government, CEA, Pilisaru Programme and the Provincial Councils. Here

are two examples of what we can do with a 2 litre PET Bottle:

Example 1: A small hotel in Arugambay was reusing the PET Bottles as

lampshades in their garden.

Example 2: Plastic Soda Bottle Lamp - An improvisation to light up

dark spaces using the sunlight during the daytime. The bottle is filled

with clean water, and about 3 tablespoons of liquid bleach is added to

prevent algae growth. The bottle is tightly capped, and secured on the

roof, with a part of the bottle above the roof and the rest below the

roofing sheet.

The sunlight enters through the upper part of the bottle, gets

refracted within it, and is emitted from the lower part, diffusing light

into the dark interior of the room. This simple device is bringing

happiness to so may people living in dark, crowded shanties in the

developing world.

This is an example that we should definitely follow, as it has

multiple advantages of bringing light to dark spaces, particularly in

single storey houses,

warehouses, garages etc. utilizing sunlight, at very little initial

cost and no operating cost at all and reuses plastic that would have

needed disposal or recycling. If this idea can be propagated in the

country, it is certainly going to help reduce the cost of electricity or

kerosene used to light up homes, and would improve the living condition

of some of the underserved homes.

Thus we can see that the main issues of Solid Waste in Sri Lanka are

the very high quantities that are generated and the characteristics of

the waste, and the issues arising from what happens to the waste if we

just allow it to remain in the environment, such as aesthetic effects,

health issues, effects on wild animals, air, water and soil pollution

and increase in Global Warming potential.

Our country has adequate legislation, regulations and organizational

structure, but the main cause of the poor state of affairs seems to be

the failure of the public to take responsibility for the waste that they

generate, and not concentrating our efforts on the prevention of waste

generation and looking for alternative uses rather than throwing these

resources away.

However, there is hope for a better future because the younger

generation is much more sensitive to the environmental impacts of this

unsustainable behaviour, but we need to provide them the necessary

support. We can see that things are moving in the right direction, with

the support of the Ministries of Environment and Local Government, CEA,

Pilisaru Programme and the Provincial Councils, and some private sector

participation too.

(The writer is a

Senior Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of

Moratuwa) |