Psychosocial problems of Child Soldiers

Professor Daya Somasundaram/Dr Ruwan M Jayatunge

In war and violent conflict, children are traumatized by such common

experiences as frequent shelling, bombing, helicopter strafing,

round-ups, cordon-off and search operations, deaths, injury,

destruction, mass arrests, detention, shootings, grenade explosions and

landmines. Studies focusing on children in war situations for example in

Mozambique (Richman et al, 1988)and Philippines(CRC, 1986) report

considerable psychological sequelae.

In addition to the direct effects on children, war also results in

collective trauma at the family and community levels. There is a

breakdown of family and community processes, support structures and

networks, ethical and moral values, cohesion and purpose. In this

uncertain, insecure and hopeless environment, children are more likely

to look for alternative opportunities, follow alluring possibilities and

be compelled to make unwholesome choices. Brutalization resulting from

growing up with violence, impunity and injustice with vulnerability,

fear for their safety and real threats would motivate them to protect

themselves (and in their imagination, their families and community) with

arms and training.

Deprivation

Many families that are displaced, without incomes, jobs and food may

encourage one of their children to join, so that at least they have

something to eat. There is a higher incidence of malnutrition and ill

health in the war torn areas. Allocation and distribution of health care

facilities (staff, drugs, equipment) to some areas may be markedly

disproportional. Education and schools become disorganized. There are

often real or perceived inequalities in opportunities for and access to

further education, sports, foreign scholarships or jobs for some groups

compared to other more privileged groups. For the more conscious and

concerned children, seeing or experiencing these deprivations for their

family and community would push them into joining an armed resistance

group.

Socio-cultural factors

|

|

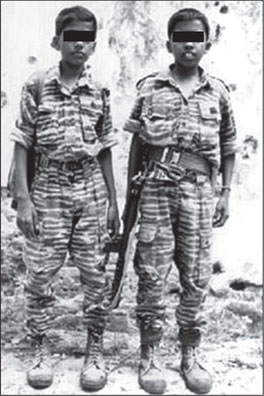

Former LTTE

Child Soldiers. File photo |

Another potent push factor is oppressive social practices where the

lower classes and castes are suppressed by the higher, who hold power

and authority. For many from the lower classes, joining them becomes a

way out of this oppressive system. Similarly, for younger females who

experience the patriarchal oppression against their sex, it is a means

of escape and 'liberation'.

Pull factors

Children because of their age, immaturity, curiosity and love for

adventure are susceptible to 'Pied Piper' enticement through a variety

of psychological methods. Public displays of war paraphernalia, funerals

and posters of fallen cadres, speeches and videos, particularly in

schools; heroic, melodious songs and stories, drawing out feelings of

patriotism and creating a martyr cult create a compelling milieu. Severe

restrictions on leaving areas create a feeling of entrapment as well as

ensure that there is a continuing source of recruits. Military type

training instill a military thinking.

In war and violent circumstances, socio-cultural and religious

leaders and institutions do not protect or protest against child

recruitment.

Psychological consequences

Apart from death and injury, the recruitment of children becomes even

more abhorrent when one sees the psychological consequences. In those

that came for treatment, we found a whole spectrum of conditions from

neurotic conditions like somatization, depression, PTSD to more severe

reactive psychosis and Malignant PTSD, which leaves them as complete

psychological and social wrecks.

Numerous studies have shown that Child Soldiers are at high risk of

developing PTSD. Okello, Onen, and Musisiv (2007) found that 27 percent

- 34.9 percent of Ugandan Child Soldiers suffered PTSD. Kohrt et el. (

2011) found that 75 of the Nepali Child Soldiers (52.3 percent) met the

symptom cutoff score for depression, 65 (46.1 percent) met the score for

anxiety 78 (55.3 percent) met the criteria for PTSD, 55 (39 percent) met

the criteria for general psychological difficulties, and 88 (62.4

percent) were functionally impaired.

A study conducted in Sri Lanka found higher rates of PTSD in children

than adults who are recruited. The emotional consequences for the

majority of the children interviewed included sad moods, preoccupations,

suicidal thoughts and fears. Most of them experienced loss in relation

to the death of members of their family and social status as a result of

their actions. This study also found that while all children in Sri

Lanka grew up as a generation knowing nothing but war, and being

subjected to indoctrination so they would feel hatred against their

enemy, the children who were conscripted were from families living in

poverty. Children from privileged families either migrated out of the

area or would have been released if they were conscripted (de Silva,

Hobbs and Hanks, 2001).

Political violence

Garbarino and Kostelny, (1993) suggest that experiences related to

political violence and war might constitute a serious risk for the

well-functioning family. Most of the Child Soldiers were separated from

their parents for a long period and many have lost the sense of family

belongingness.

Their family ties are wrecked. These children are separated from

their cultural, social and moral identity, and it makes them vulnerable

to psychological and social ill effects. Those with PTSD have intrusive

memories of the war, flashbacks, emotional arousal, emotional numbing

and various other anxiety related symptoms. Many avoid places and

conversations related to their past experiences. Some children are

reluctant to go back to their native villages may be due to shame or

guilt.

Avoidance, as described by the former Child Soldiers, included

actively identifying social situations, physical locations or activities

that had triggered an emergence of post-traumatic stress symptoms in the

past, and making efforts to avoid them in the future. One of the

strongest traumatic re-experience triggers was physical location: some

former Child Soldiers are now avoiding places where they witnessed or

participated in violent and inhumane atrocities. War affects children in

all the ways it affects adults, but also in different ways.

Combat trauma could affect children in all aspects of their lives

causing long term effects that are now termed complex PTSD. Common

symptoms would include affect dysregulation characterized by persistent

dysphoria, chronic suicidal preoccupation, self-injury and explosive

anger; dissociative episodes (which in African countries can be in the

form of trance or possession states); somatization, memory disturbances,

sense of helplessness and hopelessness; isolation and withdrawal, poor

relationships, distrust and loss of faith.

Our observation has been that children are particularly vulnerable

during their impressionable formative period, causing permanent scarring

of their developing personality. Rebels have expressed their preference

for younger recruits as “they are less likely to question orders from

adults and are more likely to be fearless, as they do not appreciate the

dangers they face. Their size and agility makes them ideal for hazardous

and clandestine assignments.”

Some of the Child Soldiers have managed to escape from their country

but are still living with past memories of war. A study conducted by

Kanagaratnam et al (2005) focuses on ideological commitment and

post-traumatic stress in a sample of former Child Soldiers from Sri

Lanka living in exile in Norway. Using a sample of 20 former Child

Soldiers the researchers tried to find a correlation between ideological

commitment and developing mental health problems.

Usually female Child Soldiers face hardships in the war front. Female

Child Soldiers in Uganda, Sierra Leone and in Congo were frequently used

as sex slaves and they were repetitively raped by the adult fighters.

The LTTE used female Child Soldiers to commit murders when they attacked

endangered villagers. There were groups of female LTTE cadres who mainly

consisted of underage girls called 'Clearance Party'. The Clearance

Party advances after the assault group; their main task was to kill the

wounded civilians or soldiers by using machetes. As the researcher

Hamblen (1999) pointed out Gender appears to be a risk factor for PTSD;

several studies suggest girls are more likely than boys to develop PTSD.

Attachment problems

When the children were forcibly removed from their parents many

children experienced separation anxiety. Some developed into full blown

symptoms of Separation Anxiety Disorder. These children repeatedly cry,

attempt to run away from the captors, they have fear of being alone, and

sometimes troubled by nightmares. The senior cadres use physical

violence and intimidation to train the newly recruited Child Soldiers.

The British Psychologist John Bowlby believed that attachment behaviors

are instinctive and will be activated by any conditions that seem to

threaten the achievement of proximity, such as separation, insecurity

and fear.

Many ex-child combatants have apathy and poor attachment with their

parents. The parents often feel that their child has changed

dramatically and he is unable to express love and warmth in return. Some

express that there is an invisible wall between parents and the child.

The child seems to have lost the sense of trust in adults and feels that

he has lost his identity as a valuable member of the society.

The child becomes oppositional, defiant, and impulsive and parents

feel that the child acts as if adults don't exist in their world and

does not look to adults for positive interactions. Some children had

created bonds with their abductors during their stay with them and feel

that they had better time with the militants than with the parents.

Moral development

Children's moral development can be disrupted by their participation

in armed conflicts. Normally children learn to conform to a number of

social rules and expectations as they become participants in the

culture. Children and adolescents who had been displaced by civil war in

Colombia reported expecting that they and others would steal and hurt

people despite acknowledging that it would be morally wrong to do so,

and many of them, especially adolescents, judged that taking revenge

against some groups was justifiable.

Social learning theorists like Albert Bandura claim that children

initially learn how to behave morally through modeling. Many Child

Soldiers had learned their social behaviour through adult militants and

for a number of years these senior figures were their role models. They

had learned that aggression and violence were acceptable behaviours and

killing the enemy was correct. They were constantly taught that

kindness, compassion and forgiveness were signs of weakness.

The senior members of the rebel forces did killings and torture in

front of the children for them to observe and learn. According to

Bandura's postulation, individuals acquire aggressive responses using

the same mechanism that they do for other complex forms of social

behaviour: direct experience or the observation-modeling of others. For

a number of years violence had become a way of life for these children.

For years they believed that violence was a legitimate means of

achieving one's aims and it was an accepted form of behaviour. They find

it difficult to disengage from violent thoughts and have a transition to

a non-violent lifestyle.

Participation in war and indoctrination into the ideologies of hatred

and violence leaves children's moral sensibilities distorted. Children

may hand over their guns, but they cannot so easily abandon the violent

ways of thinking in which they have been trained. Part of demobilization

is enabling the child to move away from violence and into a more

inclusive and constructive way of life. The inclusion of Peace Education

in curricula facilitates this process.

|