|

Bhuddist Spectrum

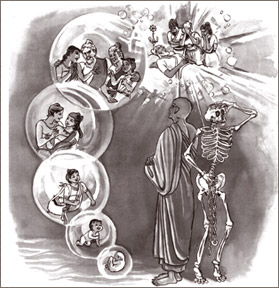

Meeting the divine messengers

Bhikkhu Bodhi

The traditional legend of the Buddha's quest for enlightenment tells

us that throughout his youth and early manhood Prince Siddhattha, the

Bodhisatta, lived in complete ignorance of the most elementary facts of

human life. His father, anxious to protect his sensitive son from

exposure to suffering, kept him an unwitting captive of nescience.

Incarcerated in the splendor of his palace, amply supplied with sensual

pleasures and surrounded by merry friends, the prince did not entertain

even the faintest suspicion that life could offer anything other than an

endless succession of amusements and festivities.

Fateful event

It was only on that fateful day in his twenty-ninth year, when

curiosity led him out beyond the palace walls, that he encountered the

four "divine messengers" that were to change his destiny. The first

three were the old man, the sick man, and the corpse, which taught him

the shocking truths of old age, illness, and death; the fourth was a

wandering ascetic, who revealed to him the existence of a path whereby

all suffering can be fully transcended.

This charming story, which has nurtured the faith of Buddhists

through the centuries, enshrines at its heart a profound psychological

truth. In the language of myth it speaks to us, not merely of events

that may have taken place centuries ago, but of a process of awakening

through which each of us must pass if the Dhamma is to come to life

within ourselves. This charming story, which has nurtured the faith of Buddhists

through the centuries, enshrines at its heart a profound psychological

truth. In the language of myth it speaks to us, not merely of events

that may have taken place centuries ago, but of a process of awakening

through which each of us must pass if the Dhamma is to come to life

within ourselves.

Beneath the symbolic veneer of the ancient legend we can see that

Prince Siddhattha's youthful sojourn in the palace was not so different

from the way in which most of us today pass our entire lives often,

sadly, until it is too late to strike out in a new direction. Our homes

may not be royal palaces, and the wealth at our disposal may not

approach anywhere near that of a North Indian rajah, but we share with

the young Prince Siddhattha a blissful (and often willful) oblivion to

stark realities that are constantly thrusting themselves on our

attention.

Comfortable life

If the Dhamma is to be more than the bland, humdrum background of a

comfortable life, if it is to become the inspiring, sometimes grating

voice that steers us on to the great path of awakening, we ourselves

must emulate the Bodhisatta in his process of maturation. We must join

him on that journey outside the palace walls - the walls of our own

self-assuring preconceptions - and see for ourselves the divine

messengers we so often miss because our eyes are fixed on "more

important things," i.e., on our mundane preoccupations and goals.

The Buddha says that there are few who are stirred by things that are

truly stirring, compared to those people, far more numerous, who are not

so stirred. The spurs to awakening press in on us from all sides, yet

too often, instead of acknowledging them, we respond simply by putting

on another layer of clothes to protect ourselves from their sting.

This statement is not disproved even by the recent deluge of

discussion and literature on aging, life-threatening illnesses, and

alternative approaches to death and dying. For open and honest awareness

is still not sufficient for the divine messengers to get their message

across. In order for them to convey their message, the message that can

goad us on to the path to liberation, something more is needed. We must

confront aging, illness, and death, not simply as inescapable realities

with which we must somehow cope at the practical level, but as envoys

from the beyond, from the far shore, disclosing new dimensions of

meaning.

This disclosure takes place at two levels. First, to become divine

messengers, the facts of aging, illness, and death must jolt us into an

awareness of the fragile, precarious nature of our normal day-to-day

lives. They must impress upon our minds the radical deficiency that runs

through all our worldly concerns, extending to conditioned existence in

its totality. Thereby they become windows opening upon the first noble

truth, the noble truth of suffering, which the Buddha says comprises not

only birth, aging, illness, and death, not only sorrow, grief, pain, and

misery, but all the "five aggregates of clinging" that make up our

being-in-the-world.

When we meet the divine messengers at this level, they become

catalysts that can induce in us a profound internal transformation. We

realize that because we are frail and inescapably mortal we must make

drastic changes in our existential priorities and personal values.

Instead of letting our lives be consumed by transient trivia, by things

that are here today and gone tomorrow, we must give weight to "what

really counts," to aims and actions that will exert a lasting influence

upon our long-range destinies - upon our final destiny in this life, and

upon our ultimate direction in the cycle of repeated birth and death.

Personal playground

Before such a revaluation takes place, we generally live in a

condition that the Buddha describes by the term pamada, negligence or

heedlessness. Imagining ourselves immortal, and the world our personal

playground, we devote our energies to the accumulation of wealth, the

enjoyment of sensual pleasures, the achievement of status, the quest for

fame and renown.

The remedy for heedlessness is the very same quality that was aroused

in the Bodhisatta when he met the divine messengers in the streets of

Kapilavatthu. This quality, called in Pali samvega, is a sense of

urgency, an inner commotion or shock which does not allow us to rest

content with our habitual adjustment to the world. Instead it drives us

on, out of our cozy palaces and into unfamiliar jungles, to work out

with diligence an authentic solution to our existential plight.

It is at this point that the second function of the divine messengers

comes to prominence. For aging, sickness, and death are not only emblems

of the unsatisfactory nature of mundane existence but pointers to a

deeper reality that lies beyond. In the traditional legend the old man,

the sick man, and the corpse are gods in disguise; they have been sent

down to earth from the highest heaven to awaken the Bodhisatta to his

momentous mission, and once they have delivered their message they

resume their celestial forms.

The final word of the Dhamma is not surrender, not an injunction to

resign ourselves stoically to old age, sickness, and death. This is the

preliminary message, the announcement that our house is ablaze. The

final message is other: an ebullient cry that there is a place of

safety, an open field beyond the flames, and a clear exit sign pointing

the way of escape.

If in this process of awakening we must meet old age, sickness, and

death face to face, that is because the place of safety can be reached

only by honest confrontation with the stark truths about human

existence. We cannot reach safety by pretending that the flames that

engulf our home are nothing but bouquets of flowers: we must see them as

they are, as real flames.

When, however, we do look at the divine messengers squarely, without

embarrassment or fear, we will find that their faces undergo an

unexpected metamorphosis. Before our eyes, by subtle degrees, they

change into another face - the face of the Buddha, with its serene smile

of triumph over the army of Mara, over the demons of Desire and Death.

The divine messengers point to what lies beyond the transient, to a

dimension of reality where there is no more aging, no more sickness, and

no more death. This is the goal and final destination of the Buddhist

path - Nibbana, the Unaging, the Unailing, the Deathless. It is to

direct us there that the divine messengers have appeared in our midst,

and the good news of deliverance is their message.

www.accesstoinsight.org

Meditation for daily life:

Strengthening concentration power

Dr Padmaka Silva

If there is a person in whom a Samadhi has developed and if he wishes

to make use of that Samadhi and in order to strengthen that Samadhi, he

should meditate in the morning, day and night. If he remains without

meditating it becomes impossible to strengthen that Samadhi. He fails to

get the comfort associated with Samadhi. Although he feels at some time

that it does not develop it develops at least to a small extent. It is

like climbing a hill. Doesnt he ascend the hill slowly even using a

walking stick? Although he thinks it does not develop it develops

internally at least little by little.

|

|

Reciting is one good way to proper

meditation. AFP |

He thinks it is not developing on thinking of a time when it was

developing. Suppose meditation develops well in the day time. But it

does not happen in the same way in the morning. Then he thinks it is not

developing. But even at that time it takes place even to a small extent.

Therefore try to carry out these meditations systematically throughout

the entire day. If not it will not be possible to achieve a success.

Arising comfort

The next matter is that an individual who does not meditate in the

morning, daytime and night in this manner fails to achieve the comfort

arising from meditation because he meditates only at one time. He does

not meditate at different times.

Different times

Thereby he does not achieve the comfort arising from meditation. If

he meditates in a balanced manner it becomes possible to remain in

comfort.

Actually it is possible to attain some comfort only by meditating.

The ability to reduce Raga, Dosa and Moha (greed, aversion and illusion)

arises only through meditation. That reduction itself causes some

comfort. But it is not a complete comfort.

Raga, Dosa and Moha get thinned down and suppressed in an individual

who meditates even for a short while. Then he gets some comfort. If he

carries out the meditation well at different times throughout the day in

a balanced manner his merit becomes strong. When the merit side becomes

strong, sins start wearing off.

(Compiled with instructions given by Ven Nawalapitiye Ariyawansa

Thera)

[email protected]

To be continued

Metta means goodwill

Thanissaro Bhikkhu

Notice that last statement: "May they look after themselves with

ease." You're not saying that you're going to be there for all beings

all the time. And most beings would be happier knowing that they could

depend on themselves rather than having to depend on you. I once heard a

Dharma teacher say that he wouldn't want to live in a world where there

was no suffering because then he wouldn't be able to express his

compassion which when you think about it, is an extremely selfish

wish. He needs other people to suffer so he can feel good about

expressing his compassion? A better attitude would be, "May all beings

be happy. May they be able to look after themselves with ease." That way

they can have the happiness of independence and self-reliance.

|

|

Promoting

true happiness for all |

Another set of metta phrases is in the Karaniya Metta Sutta. They

start out with a simple wish for happiness:

Happy at heart

Happy, at rest, may all beings be happy at heart. Whatever beings

there may be, weak or strong, without exception, long, large, middling,

short, subtle, blatant, seen unseen, near far, born seeking birth: May

all beings be happy at heart.

But then they continue with a wish that all beings avoid the causes

that would lead them to unhappiness:

Let no one deceive another or despise anyone anywhere, or through

anger or resistance wish for another to suffer.

- Snp 1.8

In repeating these phrases, you wish not only that beings be happy,

but also that they avoid the actions that would lead to bad karma, to

their own unhappiness. You realize that happiness has to depend on

action: For people to find true happiness, they have to understand the

causes for happiness and act on them. They also have to understand that

true happiness is harmless. If it depends on something that harms

others, it's not going to last. Those who are harmed are sure to do what

they can to destroy that happiness. And then there's the plain quality

of sympathy: If you see someone suffering, it's painful. If you have any

sensitivity at all, it's hard to feel happy when you know that your

happiness is causing suffering for others.

So again, when you express goodwill, you're not saying that you're

going to be there for them all the time. You're hoping that all beings

will wise up about how to find happiness and be there for themselves.

The Karaniya Metta Sutta goes on to say that when you're developing

this attitude, you want to protect it in the same way that a mother

would protect her only child.

As a mother would risk her life to protect her child, her only child,

even so should one cultivate a limitless heart with regard to all

beings.

Some people misread this passage - in fact, many translators have

mistranslated it - thinking that the Buddha is telling us to cherish all

living beings the same way a mother would cherish her only child. But

that's not what he's actually saying. To begin with, he doesn't mention

the word "cherish" at all. And instead of drawing a parallel between

protecting your only child and protecting other beings, he draws the

parallel between protecting the child and protecting your goodwill. This

fits in with his other teachings in the Canon. Nowhere does he tell

people to throw down their lives to prevent every cruelty and injustice

in the world, but he does praise his followers for being willing to

throw down their lives for their precepts:

Just as the ocean is stable and does not overstep its tideline, in

the same way my disciples do not - even for the sake of their lives -

overstep the training rules I have formulated for them.

- Ud 5.5

The verses here carry a similar sentiment: You should be devoted to

cultivating and protecting your goodwill to make sure that your virtuous

intentions don't waver. This is because you don't want to harm anyone.

Harm can happen most easily when there's a lapse in your goodwill, so

you do whatever you can to protect this attitude at all times. This is

why, as the Buddha says toward the end of the sutta, you should stay

determined to practice this form of mindfulness: the mindfulness of

keeping in mind your wish that all beings be happy, to make sure that it

always informs the motivation for everything you do.

Thoughts of metta

This is why the Buddha explicitly recommends developing thoughts of

metta in two situations where it's especially important - and especially

difficult - to maintain skillful motivation: when others are hurting

you, and when you realize that you've hurt others.

If others are harming you with their words or actions - "even if

bandits were to carve you up savagely, limb by limb, with a two-handled

saw" - the Buddha recommends training your mind in this way:

Our minds will be unaffected and we will say no evil words. We will

remain sympathetic, with a mind of goodwill, and with no inner hate. We

will keep pervading these people with an awareness imbued with goodwill

and, beginning with them, we will keep pervading the all-encompassing

world with an awareness imbued with goodwill abundant, expansive,

immeasurable, free from hostility, free from ill will. MN 21

In doing this, the Buddha says, you make your mind as expansive as

the River Ganges or as large as the earth in other words, larger than

the harm those people are doing or threatening to do to you. He himself

embodied this teaching after Devadatta's attempt on his life. As he told

Mara - who had come to taunt him while he was resting from a painful

injury - "I lie down with sympathy for all beings." (SN 4.13) When you

can maintain this enlarged state of mind in the face of pain, the harm

that others can do to you doesn't seem so overwhelming, and you're less

likely to respond in unskillful ways. You provide protection - both for

yourself and for others against any unskillful things you otherwise

might be tempted to do.

As for the times when you realize that you've harmed others, the

Buddha recommends that you understand that remorse is not going to undo

the harm, so if an apology is appropriate, you apologize. In any case,

you resolve not to repeat the harmful action again. Then you spread

thoughts of goodwill in all directions.

This accomplishes several things. It reminds you of your own

goodness, so that you don't - in defense of your self-image - revert to

the sort of denial that refuses to admit that any harm was done. It

strengthens your determination to stick with your resolve not to do

harm. And it forces you to examine your actions to see their actual

effect: If any other of your habits are harmful, you want to abandon

them before they cause further harm. In other words, you don't want your

goodwill to be just an ungrounded, floating idea. You want to apply it

scrupulously to the nitty-gritty of all your interactions with others.

That way your goodwill becomes honest. And it actually does have an

impact, which is why we develop this attitude to begin with: to make

sure that it actually does animate our thoughts, words, and deeds in a

way that leads to a happiness harmless for all.

Finally, there's a passage where the Buddha taught the monks a chant

for spreading goodwill to all snakes and other creeping things. The

story goes that a monk meditating in a forest was bitten by a snake and

died. The monks reported this to the Buddha and he replied that if that

monk had spread goodwill to all four great families of snakes, the snake

wouldn't have bitten him. Then the Buddha taught the monks a protective

chant for expressing metta not only for snakes, but also for all beings.

I have good will for footless beings, good will for two-footed

beings, good will for four-footed beings, good will for many-footed

beings. May footless beings do me no harm. May two-footed beings do me

no harm. May four-footed beings do me no harm. May many-footed beings do

me no harm. May all creatures, all breathing things, all beings each

every one - meet with good fortune. May none of them come to any evil.

Limitless is the Buddha, limitless the Dhamma, limitless the Sangha.

There is a limit to creeping things: snakes, scorpions, centipedes,

spiders, lizards, rats. I have made this safeguard, I have made this

protection. May the beings depart.

AN 4.67

Different species

The last statement in this expression of metta takes into

consideration the truth that living together is often difficult

especially for beings of different species that can harm one another

and the happiest policy for all concerned is often to live harmlessly

apart.

These different ways of expressing metta show that metta is not

necessarily the quality of loving kindness. Metta is better thought of

as goodwill, and for two reasons. The first is that goodwill is an

attitude you can express for everyone without fear of being hypocritical

or unrealistic. It recognizes that people will become truly happy not as

a result of your caring for them but as a result of their own skillful

actions, and that the happiness of self-reliance is greater than any

happiness that comes from dependency.

The second reason is that goodwill is a more skillful feeling to have

toward those who would be suspicious of your lovingkindness or try to

take advantage of it. There are probably people you've harmed in the

past who would rather not have anything to do with you ever again, so

the intimacy of lovingkindness would actually be a source of pain for

them, rather than joy. There are also people who, when they see that you

want to express lovingkindness, would be quick to take advantage of it.

Concluded

|