|

Buddhist Spectrum

Establishment of Maha Bodhi Society

Priyanka KURUGALA

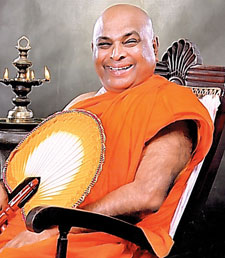

Ven Dodangoda Rewatha Thera is currently the General Secretary of

Mahabodhi Society, India, also holding the position of Chief

Sanghanayaka of India. He is in the forefront re-breathing life into

Anagarika Dharmapala’s mission of protecting Buddhism. Daily News

Buddhist Spectrum spoke to him with the objective of tracing the roots

of Maha Bodhi Society, India.

|

Ven Rewatha Thera |

Pilgrims fond of visiting the Buddha’s land now have a number of

facilities. They have proper accommodation too. A century ago, however,

when Anagarika Dharmapala initiated his mission, things were in a dire

situation. Pilgrims had quite a lot of difficulties to face.

From Calcutta he traveled to Varanasi by train. When he reached the

destination, Anagarika Dharmapala could see a flock of bull carts

carrying broken building materials. He inquired and knew the materials

were the remains of Moolagandhakuti temple. The remains were being

transported to be reused to build houses.

Anagarika Dharmapala was shocked! He sat down on the ground and wept,

it is said.

He was determined to protect the sacred site from Buddhist infidels.

The site was covered by thick forests. Dhammika Chithya was the only

significant point of the area. It had no proper accommodation. Young

Dharmapala could locate a big Nuga tree in close proximity to the

Dhammika Chithya. He selected this place as his accommodation for the

first night in India. Then Anagarika Dharmapala wrote a letter to his

mother pleading her blessing to rescue the Bodh Gaya. He required family

wealth to work on the rescue mission.

It was no piece of cake to reach Bodh Gaya at the time. The place was

governed by Krishna Dayal Giri Mahantha, a Hindu priest. Dharmapala was

not allowed entry. At last he was allowed when he accompanied two monks:

Japanese and Sri Lankan. He was further shocked to see what had occurred

in the temple. Mahantha had completely changed a Buddha statue. It had

been remoulded into Hindu icons such as earrings. Next to the statue was

a Shiva Lingam meant to invoke blessings on Hindus.

Dharmpala recited Sathipattana sutta in front of the Vajrasana of the

Jaya Sri Maha Bodhi. He made a firm resolution that he would protect

this sacred Buddhist site for the Buddhists all over the world.

Following Asoka’s empire, India did not have a Buddhist leader for

800 years. Every Buddhist temple was taken advantage of by Mongol

empires and the situation led to massive Hindu domination. Upon hearing

Colonel Henry Olcott’s speeches, young Dharmapala was keen to go to

India and sight the remains of sacred cities.

Dharmapala had serious discussions with Ven Hikkaduwe Sumangala Thera.

They established the Indian Mahabodi Society in 1891. He appointed

members for each country to interpret as an agent of the Mahabodhi

Society to rescue the Gaya for Buddhists. He failed, for the first time,

and did not get sufficient support from other countries.

|

Bodh Gaya |

He cased a file in the court of Gaya, but the judgment was not in his

favour. He appealed another time. The Hindus, led by Mahantha, were of

the opinion that the Buddha a ghost of Vishnu, hence Gaya is property of

Hinduism.

Meanwhile the first Indian President Rajendra Prasad appointed a

committee with the participation of four Buddhists and four Hindus to

solve this problem. The verdict was that the site belongs to Buddhists

as well as Hindus. The committee is in charge of the society to date.

It was only Rabindranath Tagore who directly supported the Buddhist

mission. In 2002 the UNESCO proclaimed this site as a world heritage. A

Brahman family in Calcutta, called Mukardhi, offered great support to

Dharmapala. That Dharmapala worked against the Hindus is an incorrect

impression. He only wanted to rescue a sacred Buddhist site from harmful

Hindu infiltrations.

Even after becoming a monk Ven Devamitta could not see the results of

his efforts. He constantly fell prey to Hindu assaults. He was

imprisoned too. Even Sri Lankan Buddhists attacked him. It took a long

time to see the modern Bodh Gaya available with many facilities to

Buddhist pilgrims.

But how many people have paid their attention and gratitude to

Anagarika Dharmapala? At present, most of pilgrims have lost their

religious targets and activities. Their aims lie on Business and

shopping purposes. Buddhists hardly know they are Buddhists - or at

least their Buddhist role. There may be ceremonial Buddhists in India,

but there is hardly any Buddhist in Bodh Gaya. There are three kinds of

Buddhists in India: traditional, Mahayana and Ambedkar Buddhists. Around

45 percent Indians are Buddhists. They need monks’ guidance, and

accordingly they respect the monks too. They accept monks with grace and

discuss their daily problems with them.

Maha Bodhi Society has attempted to fulfill this vacuum by

encouraging Buddhist monks to visit India to continue the Dharmapala

mission. But the crux of the issue is most monks are not equipped with

thorough knowledge on the Buddha’s teachings nor do they have excellence

of practice. Both are essential for dedication to the mission. To make

things worse, they do not have a good language command too.

The Society has drawn up a plan to train a number of monks to work on

the mission and carry on Dharmapala’s message to posterity.

Validity of wholesome and unwholesome kamma

Rajah Kuruppu

An important part of the Dhamma is the Law of Kamma, the Law of

Action and Reaction. Broadly stated, under this Law, wholesome actions

lead to pleasant experiences and unwholesome actions result in

unpleasant and painful consequences. The Buddha emphasized the

importance of cetana or intention as the foremost factor in this Law.

The intention of any action, verbal, physical or mental, is important

from the Buddhist perspective. For this reason, the Buddha declared as

follows. “It is Cetana (intention) that I call Kamma, having willed one

acts by word, deed or thought”. If any action is without intention, then

Kammic consequences would not follow.

It

should, however, be noted that Kamma is action and the consequent result

is Vipaka. There is a general tendency to refer to both action and

reaction as Kamma. Often, a Buddhist would say “this is my Kamma” when

he is faced with a very unpleasant experience in life. But, it really is

not Kamma, but Kamma Vipaka, the consequence of unwholesome action. It

should, however, be noted that Kamma is action and the consequent result

is Vipaka. There is a general tendency to refer to both action and

reaction as Kamma. Often, a Buddhist would say “this is my Kamma” when

he is faced with a very unpleasant experience in life. But, it really is

not Kamma, but Kamma Vipaka, the consequence of unwholesome action.

Kamma is closely related to the Buddhist doctrine of re-birth, for

without re-birth, the validity of the Law of Kamma would be seriously

challenged. For we know from experience that some people who lead

unwholesome and selfish lives sometimes thrive in our society in this

life itself. This is explained in the Dhamma as enjoying the results of

good deeds of past lives, which could overshadow the consequences of

present unwholesome actions.

An important characteristic of Kamma is that it is only the results

of good or bad deeds one could take from this life to another. All our

possessions and relationships cannot be taken to the next life since

they are not valid currency in life beyond.

Dhammapada and Kamma:

The question is often raised whether the harmful effects of

unwholesome Kamma could be overcome with wholesome Kamma. In fact, there

are two stanzas in the Dhammapada, a collection of important sayings of

the Buddha, which appear to contradict each other. The Servants of the

Buddha Society meet every Saturday evening at Lauries Road,

Bambalapitiya, to listen to a talk on the Dhamma, discuss the Dhamma and

engage in a brief Buddhist meditation session. Recently, Dr Ranjan de

Silva, a medical doctor who served with the World Health Organization in

New Delhi, and a frequent participant in these Buddhist discussions,

quoted these two relevant stanzas from the Dhammapada. The first stanza

reads as follows:

“Na antalikkhe na samuddamajjhe

na pabbatanam vivaram pavissa

Na vijjati so jagatippadeso

yatthatthito munceyya papakamma”

“Not in the sky, nor in mid-ocean, nor in a mountain cave, is found

that place on earth where abiding one may escape from (the consequences)

of one’s evil deed.”

The second stanza reads thus -

“Yassa papam katam kammam

Kusalena pithiyati

So imam lokam pabhasseti

abbha mutto va candima”

“Whoever, by a good deed, covers the evil deed, such a one illumines

this world like the moon freed from clouds”. To be continued

The Buddha, the sensible rationalist

Dr Prabhakar Kamath

He is arguably the greatest Indian ever, and one of the greatest

thinkers in the history of the world. Most of what we know of him comes

to us from various Buddhist literature, memorized, and orally

transmitted from generation to generation, and finally written down

nearly four hundred years after his death in 483 B. C. Even though he

was certainly a historical figure, most supernatural events, and

irrational beliefs attributed to him must certainly be due to

embellishment by overenthusiastic later adherents of Buddhism. Most of

the initial converts were Brahmins, who brought with them their

Brahmanic baggage.

I am certain that the Buddha, a rationalist to boot, would have a

hearty laugh at most mindless rituals practised by various Buddhist

sects around the world. There is no dearth of hypocrites, impostors and

opportunists in this world.

|

Gandhara Buddha statue |

The Buddha was way ahead of his time. Siddhartha Gautama was perhaps

over three thousand years ahead of his time. He was the product of the

post-Vedic ‘Age of Disillusionment”. During the period of 1000-200 BC

intellectuals of India were uniformly disgusted by the twin scourges of

decadent Brahmanism: rampant animal sacrifices sponsored by kings and

officiated by Brahmins; and inequities associated with Varna Dharma -the

class system based on the theory of unequal distribution of the Gunas of

Prakriti and Karma (comeuppance) from one’s previous lives. Upanishadism,

Jainism, and a host of other heterodox sects across the board, which

preceded Buddhism, considered the world as a miserable place to live,

thanks to Brahmanism. They were all busy trying to discover a sensible

method for the final exit from it. All these were like a bunch of cooks

who were frantically looking for the nearest exit from a kitchen on

fire.

Upanishadism and Buddhism

There is no evidence that the Buddha studied the anti-Brahmanic

Upanishadic doctrines of Brahman/Atman and Yoga before arriving at his

Four Noble Truths and Eight-fold Noble Path. The Buddha did not believe

in Brahman/Atman concept. However, meditation proposed by him was

nothing but secular form of Yoga, which later on found its way into the

Upanishadic Gita as Buddhiyoga (2:48-53). Even though the Upanishadic

doctrines were not available to the general public during this time (6th

century BC) due to them being hidden by Brahmins as Shruthis, it is

possible that intellectuals of north India had some idea as to what

their theories were for the problem of Dukkha (sorrow) here on earth and

Samsara (unending cycle of birth and death) hereafter.

We should remember here that the Upanishads considered decadent

Brahmanism as the cause of three miseries: Shokam (grief), Dwandwam

(restlessness and stress) and Karmaphalam (leading to Samsara).

Their goal was to dismantle the very foundation of Brahmanism, namely

the Gunas of Prakriti and the Law of Karma; and to knock down its four

pillars: The Vedas, Varna Dharma, Yajnas and supremacy of Brahmins.

These were also the very goals of the Buddha, and he succeeded in doing

so for a thousand years, thanks to Ashoka the Great (ruled 272-232 B.

C.) who made Buddhism a World Religion. It will be of interest to us

here that when Upanishadists took over Arjuna Vishada (the Original Gita),

around 200 B. C. they incorporated many of Buddha’s teachings into it.

Buddha decries animal sacrifices

In accordance with his doctrine of infinite compassion for he

suffering of all living creatures, the Buddha revolted against animal

sacrifices, which had corrupted Yajnas due to greed of Brahmins:

Suttanipata: 2:7:23-26: But largesse (of the king) fired their

(Brahmins’) passions more to get; their craving grew. Once more they

sought Okkaka; with these verses newly framed: “As earth and water, gold

and silver, so are cows a primal requisite of man. Great store, great

wealth is thine; make (cow) sacrifice!

Then the king, the lord of chariots, persuaded by these Brahmins,

killed hundreds of thousands of cows in sacrifice. Cows sweet as lamb,

filling pails with milk, never hurting anyone with foot or horn -the

king had them seized by the horns and slaughtered by the sword.”

The Buddha expresses his horror:

Suttanipata: 2:7:27-30: Then the gods, the Pitrus (ancestral

spirits), Indra, the Asuras, the Rakshasas cried out as the weapon fell

on the cows, “Lo! This is injustice!” Of old there were only three

diseases -desire, want of food, and decay. Owing to the killing of the

cattle, there sprang ninety-eight diseases. This old sin of injury to

living beings has come down (to this day). Innocent cows are killed.

Priests have fallen off their virtues.

“This is how,” The Buddha concluded, “Kshatriyas and self-styled

Brahmins and others protected by rank destroyed the repute of their

caste and fell prey to desires.”

The Buddha told Kshatriyas not to waste money on Yajnas. Kutadanta

Sutta describes a parable told by the Buddha to a Brahmin who wanted to

perform a big sacrifice. In this parable, a king by the name of

Mahavijita decides to perform a great sacrifice, “that would be to my

benefit and happiness for a long time.” Recognizing the fact that the

additional taxation required for this ostentatious Yajna would ruin

people and the country, his wise minister, a capitalist to boot, tells

the king instead to invest that money to, “get rid of the thieves and

robbers plaguing the country; distribute grain and fodder to peasants;

give capital to businessmen; and pay government servants proper wages.”

This quintessential minister concludes, “Then those people, being intent

on their own occupations, will not harm the kingdom; your majesty’s

revenues will be great; the land will be tranquil, and not beset by

thieves; and the people, with joy in their hearts, playing with their

children, will dwell in open houses.” Thus enlightened, the king

followed his minister’s advice and consequently his kingdom prospered.

This advice is valid for Indian government to this very day.

Ashoka the Great followed this example and acted selflessly for the

welfare of all people in his kingdom. Whereas Brahmins used his negative

image (of a fallen and renegade Kshatriya who abandoned Brahmanism and

embraced Buddhism) to describe a pathetic Arjuna contemplating

abandoning his Dharma in Arjuna Vishada, (the Original Gita, 1:28-47),

Upanishadists used his positive image of an enlightened and energetic

king who worked incessantly for the welfare of all people as their model

of Karmayogi (3:20).

The Buddha opposed Varna Dharma. In defiance of Brahmanism, which

considered Brahmins as gift of Brahman (BG: 17:23), the Buddha advocated

equality of all people. Like Upanishadists before him, he said that a

man’s character, and not his class of birth, should determine his status

in life. Assallayana Sutta describes an incident in which Brahmins

prompt a brilliant and erudite young Brahmin to debate the Buddha

regarding Varna Dharma. The boy tells the Buddha to disprove the fact

that Brahmins were superior to all other classes and true heirs to

Brahman. The Buddha engages this boy in a thought-provoking debate, and

in a stepwise manner debunks his claim and makes the boy come to the

conclusion that, in the final analysis, it is one’s moral caliber and

not class of birth that determines one’s status in life.

Those days thousands upon thousands of wandering sophists, known as

Parivrajaka, roamed the country. May of them indulged in self-torture as

the path to their salvation from sorrow and Samsara. Before he came up

with his own solutions for the Dukkha (sorrow, misery) in the world, the

Buddha tried, and then discarded severe self-denial and self-torture as

the path of enlightenment. He disliked decadent Brahmanism on the one

hand and rigorous self-torture on the other. So he developed the

doctrine of the Middle Path -moderation in everything.

He declared that after 49 days of incessant contemplation under a

tree at Bodhgaya, present day Bihar, he became enlightened, and thus

became the Buddha -the Enlightened One. What he discovered was one

hundred percent rational. All other nonsense we hear about Buddhism was

grafted on to this teaching by various vested interests, which

infiltrated his organization like a bunch of leeches in the course of

several centuries. Any organization, however great its original goals

might be, will be corrupted sooner or later by less noble-minded people.

To be continued

www.nirmuktha.com

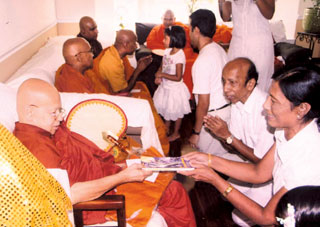

Book Launch

Damayanthi Jayakody’s latest book Gauthama Buddha Charithaya was

launched at Dayawansa Jayakody Company, New York, United States

recently. Here the author hands over the first copy to New York Buddhist

temple Viharadhipathi Ven Kurunegoda Piyathissa Nayake Thera, Ven

Pitigala Gunarathana, Ven Heenbunne Kondanna, Ven Hungampola Sirirathana,

Ven Okkampitiye Pragnarathana, publisher Dayawansa Jayakody and Uditha

Jayakody participated in the launching ceremony. |