Tea needs higher productivity

Dr N Yogaratnam

Sri Lanka having initiated action on Geographical Indication System

for the country’s tea, tea plantations and tea industry would get more

globalised and integrated into the international commodity trade.

But with the potential threat of reduction in import duties in some

countries like India, cheap teas from countries such as Vietnam could

invade the international market and pose challenges to producers.

Reducing the cost of production and increasing productivity alone will

ensure that Sri Lankan tea plantation industry is able to survive the

fiercely competitive global markets.

But statistics available 2007 for several countries show that Sri

Lanka has not performed consistently in comparison with most competing

countries of South East Asia in 2007 as far as productivity is

concerned.

India had productivity of 1,663 kg a hectare, Sri Lanka had 1,615 kg,

Vietnam had 1,548 kg, Indonesia had 1,115 kg and Bangladesh had 1,108

kg. Kenya had 2,477 kg per hectare. But, now differences in yield, cost

of production and prices have made the profitability of tea vary widely

across the different countries. Among the various countries, the highest

profitability has been obtained by Kenya (over $2,000/ha), followed by

India (over $1,400/ha) with the lowest being Sri Lanka ( $1,100/ha) a

few years ago. Although the trend remains the same, the actual figures

might have changed due to various interacting factors.

And increase in productivity hinges on a variety factors, including

higher labour output, mechanisation, higher yields from superior clones

and scientific management such as proper and timely application of

fertilisers and pesticides as well as plucking of new shoots.

With their compact holdings and cost-effective operations, small

growers have been able to implement most of these conditions more

effectively than the big plantations, where the huge scale of operations

and major investments have acted as major deterrents.

With most plantations finding shortage of labour, the introduction of

manual and mechanised shearers is expected to boost labour productivity

several fold.

From an average output of 50 kg of plucked leaves per worker, the

productivity would surge to 300 kg with the use of manual shearers and

to 600 kg with mechanised shearers.

This is bound to increase labour productivity and reduce cost of

production.

But, with the legacy of large labour force, most plantations would

not be able to replace man with machines immediately. Also, given the

undulating terrains of tea plantations, application of manual and

mechanised shearers may not be possible in all areas. The cost of

re-planting with high-yielding clones would be huge for plantations.

Plantation sources say that the large social cost for plantation

labour in Sri Lanka - provision of housing, electricity and water - as

being the big burden that other competing countries do not have.

They demand that the Government provide support for this social cost.

While challenges remain before the tea industry in increasing

productivity and reducing cost of production, viable and practical

avenues should be explored.

Productivity

Productivity is defined in the classical sense, that is, as obtaining

more output for the same input. The two major inputs in the tea industry

- land and labour - are neither as abundant nor as cheap as they were

when the tea plantations were established more than 100 years ago.

Tea is among the most labour-intensive of all the plantation crops.

It has both an agricultural and a manufacturing dimension. According to

well-established precepts, 60 per cent of the income from tea is

agricultural, the balance being of an industrial nature.

Although both the agricultural and manufacturing activities, with

particular reference to labour requirement, have been discussed on few

occasions earlier, it is still considered beneficial to re-examine this

subject with the aim of facilitating an insight into the kind of

productivity gains that are possible in an effort to improve the

viability of this volatile sector.

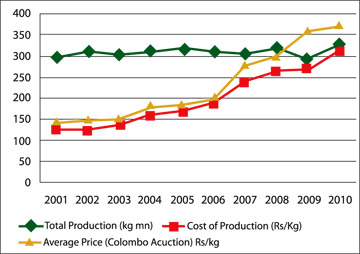

Production and COP

Tea industry is no longer a dominant source of generation of

surpluses for economic growth. An analysis of the performance of Tea,

over the last ten years, from 2001 to 2010 indicates that tea production

has increased only by 11 percent from 296 kg mn to 329 kg mn over the

ten year period , where as the COP has gone by about 159 percent over

the same period (see figures 1).

This figure may be still higher with the recent wage hike.

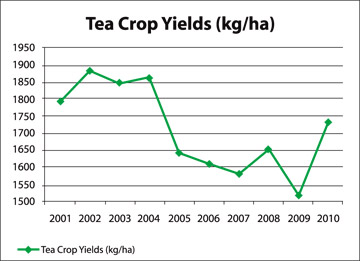

Productivity (Yield/ha) has also not been consistent ( Figure 2).

Looking at prices over the same period, tea prices have gone up by about

158 percent.

Factors influencing productivity

Harvesting: Commonly referred to as plucking in tea parlance, this

activity is overwhelmingly labour-intensive, despite the tendency lately

in some areas of the tea growing regions to use shear harvesters during

the heavy cropping period when labour is scarce. Plucking accounts for

about 70 per cent of the workdays on estates and about 40 per cent of

the total cost of production. The main factors that influence plucking

are:

Yield - a higher level being attained by adopting better agricultural

and management practices leading to enhanced plucking output;

Plant density - Fields with less plants (about 8,600 per hectare in

the “seedling” tea) having a lower plucking potential than those with

more plants (about 12,500 per hectare in vegetatively propagated tea);

Leaf variety - The small-leaved China variety yielding less than the

large-leaved “Assam” variety or the hybrid medium-leaved vegetatively

propagated plants;

Climate and topography - Higher elevation, steep areas, prolonged

drought, etc. serving as constraints to plant growth, field productivity

and, hence, plucking output;

Age of plant - Older bushes yielding less than the new and replanted

fields;

Leaf standard - The traditional “two leaves and a bud”, while

ensuring quality, does not generate as extensive a crop as does plucking

the third leaf — a practice that is now gaining ground — or even coarse

plucking, which substitutes quantity for quality;

Plucking frequency - For instance, a seven-day interval involving

about 52 rounds a year resulting in a different level of yield — and

profitability — than a five-day frequency involving about 73 rounds;

Wage rates and incentives - A properly designed incentive system, in

particular, resulting in less leaf going unplucked and, at the same

time, enhancing workers’ earnings;

Worker productivity - Embraces a wide spectrum of factors such as

earnings, motivation and socio-economic influences.

Fertilizing. Given the required soil conditions, there is a high

degree of correlation between field productivity and the application of

inorganic fertilizer, as recommended by the Tea Research Institute that

are in operation.

Apart from adhering to the recommended dosage — roughly, 1 kg of

nitrogen for every 10 kg of made tea — the industry is now looking more

closely at establishing precise linkages with fertilizer prices

(subsidies for which have, by and large, been withdrawn) as well as the

price of tea itself.

Fertilizer application continues to be a manual operation, the

workdays involved being almost the same for most fields, except that

fields with very high productivity require additional rounds which, in

turn, involve more labour, albeit to a small extent.

Weeding. Technical opinion now is that weeds in the tea fields are to

be controlled, not eradicated. It is, therefore, a question of weed

management with an eye on the cost-benefit line of the operation.

Well-maintained and productive fields with good ground cover require

little expenditure on chemicals and labour for weeding, whereas the

substantial weeding costs incurred for fields with large vacant areas

add little to productivity. Furthermore, manual weeding is slowly giving

way to chemical weeding, so that what was a labour-intensive component

of production is now no longer so, and the workforce involved in weeding

is bound to shrink further in the future.

Pruning. The average life of a seedling tea plant is well over 50

years, with hybrid types having a life of around 40 years. Pruning is

important for maintaining the tea bush in the right form and height for

growing and plucking. Pruning is also necessary for the removal of

branches that are decayed or dead as a result of drought, pests or

diseases, thereby to ensure a clean and healthy plant. The rule of thumb

is that the length of the pruning cycle is determined by the elevation

of the estate (i.e. one year for every 300 m plus one more year). In

practice, pruning is undertaken when the yield of a particular field

starts to decline.

Other field operations. These include soil conservation measures,

control of pests and diseases, and sundry activities. The labour

requirements — mostly men workers — do not vary significantly with field

productivity, being about 15 per cent of the total workdays absorbed on

an average tea estate.

Manufacturing. About 4.5 kg of freshly plucked green leaf is required

to manufacture 1 kg of black tea (finished product). In Sri Lanka,

factory expansion and modernization have not kept pace with the

additional crop generated in the field, and it has been a matter of

slowly upgrading the conventional technology. Between the two principal

methods of manufacture — orthodox and CTC (cut, tear and curl) — the

global demand for the latter has been on the rise because of its higher

cuppage (about 1.6 times more cups than its orthodox counterpart) and

greater acceptability in quick brewing tea bags.

Producing countries in the region have, accordingly, affected a shift

to CTC manufacture, with the entire Bangladesh product being of this

variety. In India, the ratio of CTC to orthodox is around 85:15, largely

reflecting a growing domestic market and shrinking exports. Sri Lanka

has traditionally been an orthodox producer, but the island has lately

affected a partial conversion to CTC manufacture, with more than 10 per

cent of output estimated to be of this variety. It is pertinent to note

that, because of the relatively continuous process which CTC entails,

the factory labour requirement is just about half that necessary for

orthodox production. This trend of lower labour absorption in tea

processing is expected to continue.

Replanting

The slow pace of replanting now is very striking. As against a

targeted rate of 1.5 to 2 per cent per annum, it is only about 0.4 per

cent in Bangladesh and India and 0.7 per cent in Sri Lanka. The

activity, which involves uprooting of old bushes, rehabilitation of

soil, planting of tea and maintenance of the young field till maturity,

is overwhelmingly labour-intensive; about 70 per cent of the cost

involved over the five-year period is on labour.

From the point of view of individual managements, the reasons for the

slow pace of replanting are economic — high investment and negative

returns. But replanting has to be seen in a wider national perspective.

By enhancing field productivity, replanting also generates much higher

employment per unit area than the old seedling fields. An element of

state intervention and assistance to give a fillip to this activity will

have a multi-dimensional impact on the long-term development of the

industry.

Meanwhile, industry efforts have been directed at the filling of

vacancies with a view to increasing the plant density per unit area

without suffering any loss of crop. To the producer, this is the most

cost-effective field development option and it also has the advantage of

absorbing underemployed workers, the labour component of infilling

being, as in replanting, about 70 per cent of plant cost and

maintenance.

Several yardsticks are available to the tea industry by which to

judge production efficiency and its effect on reducing costs, the most

important of which are discussed below.

Plucking productivity

This is the quantity of green leaf harvested per workday, the

objective being to increase it without detriment to quality. The average

for the South Asian countries in making allowances for the type of

plucking, elevation and regional differences in kg of green leaf per day

per worker, India - North, 24; South, 25, Bangladesh, 20, Sri Lanka -

corporate sector, 15 ; Smallholdings, 24.

By comparison, the Kenyan average is 40 to 50 kg of green leaf per

day per worker, although it must be added that this includes an element

of assistance by family members, especially in the smallholdings, which

adds to the individual plucker’s efforts. According to a recent study of

the African tea-producing countries, estates in Zimbabwe are registering

a plucking productivity averaging as high as 68 kg.

Processing productivity

This involves two aspects: first, the ratio of green leaf to made

tea; and second, the worker output at the factory. In regard to the

former, a combination of good quality leaf, careful handling and

transport, and timely processing will help to reduce the conversion

ratio to made tea. As noted above, 4.5:1 is the usual proportion but

this can be improved to a certain extent through better manufacturing

techniques. For example, a ratio of 4:1 is reported in Zimbabwe.

With regard to worker output, the relative position of the South

Asian countries in terms of, average factory output in kg of made tea

per day per worker is, India - North, 40; South 80, Bangladesh, 18, Sri

Lanka, Up country (orthodox), 45; Low country (orthodox), 35; CTC (cut,

tear and curl), 80.

The relatively lower worker output in the factories in North India is

attributed to the large number of workers employed for hand picking of

stalk.

Land-labour ratio

The main parameters determining the productivity of a tea estate,

particularly in respect of its day-to-day operations, are the levels of

labour utilization and the labour per unit area appropriate to the

different levels of yield.

As an example, the workdays required for an estate with a yield of,

say, 1,500 kg per hectare is reported to be around 657, with an average

of 2.74 workers per hectare. In practice, however, the latter parameter

varies from country to country and from district to district within the

same country, the average for India being 2.5 and for Bangladesh 2.

In Sri Lanka, there is a marked variation between estates and

smallholdings. In estates, there are as many as 3 to 3.5 workers per

hectare, whereas in smallholdings there are said to be as few as about

1.5, although family employment has also to be taken into account to

reflect the true position.

In the East African estate sector, the average number of workers per

hectare is reported to be 2, despite the higher yield.

Three aspects may be noted. First, workforce requirements are based

on the currently low productivity levels for existing tasks. More

cost-effective norms have to be established. When that happens and

labour productivity improves, there will be savings on labour which, in

turn, will have a salutary effect on the cost of production.

Second, the figures represent the average, not the maximum, and

especially in respect of plucking, will require an upward revision for

the heavy cropping period.

This can be calculated taking into account the yield difference

between average and peak months.

Third, where there is a situation of disguised unemployment, the use

of surplus workers in productive field development, to undertake such

tasks as replanting or infilling, would help to improve long-term

viability of the plantation.

In conclusion, if the tea industry has to choose between improving

prices and controlling costs, the former is the more difficult option

particularly in a global environment where transnational corporations

are exerting greater influence on the buying operations. |