|

Buddhist Spectrum

Buddhist meditation and depth psychology

Douglas M Burns

Mind is the forerunner of all (evil) conditions.

Mind is their chief, and they are mind-made.

If, with an impure mind, one speaks or acts,

Then suffering follows one

Even as the cart wheel follows the hoof of the ox.

Mind is the forerunner of all (good) conditions.

Mind is their chief, and they are mind-made.

If, with a pure mind, one speaks or acts,

Then happiness follows one

Like a never-departing shadow.

These words, which are the opening lines of the Dhammapada, were

spoken by Gotama Buddha 2500 years ago. They illustrate the central

theme of Buddhist teaching, the human mind. These words, which are the opening lines of the Dhammapada, were

spoken by Gotama Buddha 2500 years ago. They illustrate the central

theme of Buddhist teaching, the human mind.

Buddhism is probably the least understood of all major religions.

Indeed, from an Occidental viewpoint we might well question whether it

warrants the title of religion. In the West we are accustomed to

thinking of theology in terms of God, revelation, obedience, punishment,

and redemption.

The themes of creation, worship, judgment, and immortality have been

major concerns in the Christian heritage and are virtually inseparable

from our concept of religion. Against such a cultural background Western

man views Buddhism and in so doing unconsciously projects his own

concepts, values and expectations. Erroneously he perceives ceremonies

and bowing as examples of worship or even idolatry.

Vaguely equated

He may extol its scientific world view or abhor and condemn its

“atheism.” The Buddha is vaguely equated with God or Jesus, and

meditation is suspected of being a hypnotic approach to mysticism or an

escape from reality.

However, such erroneous notions of the Dhamma, the teaching of the

Buddha, are not entirely the result of Western ignorance and

ethnocentrism. Before his demise the Buddha predicted that within a

thousand years his doctrine would fall into the hands of men of lesser

understanding and would thereby become corrupted and distorted. Such has

been the case throughout much, if not most, of the Orient.

Ritual has replaced self-discipline, faith has replaced insight, and

prayer has replaced understanding.

If the basis of Christianity is God, the basis of Buddhism is mind.

From the Buddhist viewpoint, mind or consciousness is the core of our

existence. Pleasure and pain, good and evil, time and space, life and

death have no meaning to us apart from our awareness of them or thoughts

about them.

Whether God exists or does not exist, whether existence is primarily

spiritual or primarily material, whether we live for a few decades or

live forever — all these matters are, in the Buddhist view, secondary to

the one empirical fact of which we do have certainty: the existence of

conscious experience as it proceeds through the course of daily living.

Therefore Buddhism focuses on the mind; for happiness and sorrow,

pleasure and pain are psychological experiences. Even such notions as

purpose, value, virtue, goodness, and worth have meaning only as the

results of our attitudes and feelings.

Buddhism does not deny the reality of material existence, nor does it

ignore the very great effect that the physical world has upon us.

On the contrary, it refutes the mind-body dichotomy of the Brahmans

and says that mind and body are interdependent. But since the

fundamental reality of human existence is the ever-changing sequence of

thoughts, feelings, emotions, and perceptions which comprise conscious

experience, then, from the viewpoint of early Buddhism, the primary

concern of religion must be these very experiences which make up our

daily lives.

Most significant of these are love and hate, fear and sorrow, pride

and passion, struggle and defeat.

Conversely, such concepts as vicarious atonement, Cosmic

Consciousness, Ultimate Reality, Buddha Nature, and redemption of sins

are metaphysical and hypothetical matters of secondary importance to the

realities of daily existence.

Displeasurable experience

Therefore, in Buddhism the most significant fact of life is the first

noble truth, the inevitable existence of dukkha. Dukkha is a Pali word

embracing all types of displeasurable experience — sorrow, fear, worry,

pain, despair, discord, frustration, agitation, irritation, etc. The

second noble truth states that the cause of dukkha is desire or craving.

In various texts this cause is further explained as being threefold —

greed, hatred, and delusion.

Five components

Again, on other occasions the Buddha divided the cause of suffering

into five components — sensual lust, anger, sloth or torpor, agitation

or worry, and doubt. On still other occasions he listed ten causes of

dukkha — belief that oneself is an unchanging entity; scepticism; belief

in salvation through rites, rules and ceremonies; sensual lust; hatred;

craving for fine-material existence; craving for immaterial existence;

conceit; restlessness; and ignorance. The Third Noble Truth states that

dukkha can be overcome, and the Fourth Truth prescribes the means by

which this is achieved.

Thus, with the Fourth Noble Truth, Buddhism becomes a technique, a

discipline, a way of life designed to free people from sorrow and

improve the nature of human existence. This aspect of the Dhamma is

called the Noble Eightfold Path, and includes moral teachings,

self-discipline, development of wisdom and understanding, and

improvement of one’s environment on both a personal and social level.

These have been dealt with in previous writings and for the sake of

brevity will not be repeated here. Suffice it to remind the reader that

this essay is concerned with only one aspect of Buddhism, the practice

of meditation. The ethical, practical, and logical facets of the

Teaching are covered in other publications.

If the cause of suffering is primarily psychological, then it must

follow that the cure, also, is psychological. Therefore, we find in

Buddhism a series of “mental exercises” or meditations designed to

uncover and cure our psychic aberrations.

Mistakenly, Buddhist meditation is frequently confused with yogic

meditation, which often includes physical contortions, autohypnosis,

quests for occult powers, and an attempted union with God. None of these

are concerns or practices of the Eightfold Path.

Buddhist meditation

There are in Buddhism no drugs or stimulants, no secret teachings,

and no mystical formulae. Buddhist meditation deals exclusively with the

everyday phenomena of human consciousness. In the words of the Venerable

Nyanaponika Thera, a renowned Buddhist scholar and monk:

In its spirit of self-reliance, Satipatthana does not require any

elaborate technique or external devices. The daily life is its working

material. It has nothing to do with any exotic cults or rites nor does

it confer “initiations” or “esoteric knowledge” in any way other than by

self-enlightenment.

Using just the conditions of life it finds, Satipatthana does not

require complete seclusion or monastic life, though in some who

undertake the practice, the desire and need for these may grow.

Lest the reader suspect that some peculiarity of the “Western mind”

precludes Occidentals from the successful practice of meditation, we

should note also the words of Rear Admiral E.H. Shattock, a British

naval officer, who spent three weeks of diligent meditation practice in

a Theravada monastery near Rangoon:

Basically academic

Meditation, therefore, is a really practical occupation: it is in no

sense necessarily a religious one, though it is usually thought of as

such. It is itself basically academic, practical, and profitable. It is,

I think, necessary to emphasize this point, because so many only

associate meditation with holy or saintly people, and regard it as an

advanced form of the pious life... This is not the tale of a conversion,

but of an attempt to test the reaction of a well-tried Eastern system on

a typical Western mind.

Reading about meditation is like reading about swimming; only by

getting into the water does the aspiring swimmer begin to progress. So

it is with meditation and Buddhism in general. The Dhamma must be lived,

not merely thought. Study and contemplation are valuable tools, but life

itself is the training ground.

The following passages are attempts to put into words what must be

experienced within oneself. Or in the words of the Dhammapada: “Buddhas

only point the way. Each one must work out his own salvation with

diligence.”

Meditation is a personal experience, a subjective experience, and

consequently each of us must tread his or her own path towards the

summit of Enlightenment. By words we can instruct and encourage but

words are only symbols for reality.

Abhidhamma in practice

Dr N K G Mendis

6. The five disciples were delighted with the Buddha’s discourse and

all attained enlightenment, so that, at the end of this discourse, there

were six arahants in this world. There is an implication here that,

unless one gains insight into the No-self characteristic of existence,

it is not possible to start on the path to Enlightenment. Of the ten

fetters that bind us down to wanderings in Samsara, belief in a soul is

the first to be broken. Hence the profound importance of this discourse.

This second discourse was on a discovery which was revolutionary in

human thought. Before the Buddha’s time and even after, religious

teachers emphasized the existence of an abiding soul.

Can we verify

A skeptic would say that this soul-less doctrine is one of

hopelessness and despair and equates a sentient being to an automaton.

On the contrary, the No-self doctrine gives the sentient being the

highest sense of responsibility, the greatest amount of encouragement,

the highest measure of hope and is conducive to contentment which will

be reflected in the disciple’s attitude to other fellow beings, which is

the only way to put an end to all the strife on this earth.

Can we verify for ourselves the truth of this aspect of the Buddha’s

teaching? The Buddha urged his disciples to investigate the Dhamma. In

fact, this investigation is the second of the seven enlightenment

factors. In order to convince ourselves about the truth of this

doctrine, we have to follow the Noble Eightfold Path. By constant

mindfulness and insight meditation, we will know whether this teaching

is true or not. The bodily form is subject to disease, decay and death,

over which we have no ultimate control.

The body does not decide to move, stand, sit or lie down. These

movements are always preceded by a mental directive. So the ultimate

truth is that we cannot state that ‘the body is mine’ or ‘I am the

body.’ We do, however, use these terms, but this usage is only a

conventional expression.

Dependent on conditions

The mental components arise, exist for a moment and then perish. They

arise dependent on conditions; so, here again, according to the ultimate

truth, we cannot state that the ‘mental components are mine’ or ‘I am

the mental components.’

Now, according to this teaching of No-self, wherein lies the

responsibility, the hope and the possibility of enlightenment? As

regards bodily form, we have no ultimate control over it. Even the

Buddha and the arahants suffered bodily afflictions. Disease, decay and

death cannot be prevented. The young die through accident or disease.

Living brings in its trail all the signs of decay. Kamma alone decides

the fate of this bodily form. All we can do in this present existence is

to avoid the two extremes which the Buddha discarded, namely, indulgence

and mortification.

The rest will happen to the bodily form regardless of our

interference. This does not mean that, when the body is afflicted by

accident or disease, no attempt should be made to alleviate such

affliction if ways and means were available. A negative attitude in this

respect would amount to one of the extremes, namely, mortification. The

Buddha, too, had a physician and his name was Jivaka. On the other hand,

it is different with the mental components.

These arise dependent on conditions which are intimately connected

with what are called the “roots,” which are either unwholesome or

wholesome, found in various combinations and degrees in all worldlings,

that is, in those who have not reached Sainthood. The unwholesome roots

are:

a. Greed (lobha) in various forms and degrees;

b. Hatred or anger (dosa) in various forms and degrees;

c. Delusion (moha) or ignorance (avijja), particularly with reference

to the true nature of phenomena.

In a person tainted with greed and lust, the mental components will

be predominantly those associated with greed and lust. As a result,

volition will produce actions, bodily, verbal and mental, which will

reflect these taints and bring in their trail unpleasant consequences in

accordance with the Law of Action and Reaction (kamma). The same applies

to the other two roots of an unwholesome nature.

Unwholesome volitions

Even though our past unwholesome volitions are resulting now in

painful and unpleasant feelings, perceptions and consciousness, we can

accept these with wisdom and set out on a favourable course by replacing

the unwholesome roots by wholesome ones, that is:

a. Greed and lust by greedlessness, lustlessness and generosity

(aloba);

b. Hate and anger by hatelessness (adosa) and by kindness and

goodwill (metta);

c. Delusion by undeludedness (amoha) and by wisdom (pañña).

In the discourse, the Buddha said that, with reference to any of the

aggregates, because there is no self (‘soul’), the possibility does not

exist whereby it could be said “may my ... be thus” and “may my ... not

be thus.” The conclusion to be drawn from this is that it is futile to

expect returns from prayer, appeal, entreaty, or offering to an outside

source or by wishing and just hoping for the best.

Help we may get from outside in the form of salutary advice and

association with the wise, but, in the final analysis, as stated in

verse 276 of the Dhammapada, “striving should be done by ourselves, the

Tathagatas are only teachers.” How do we strive? It is by following the

Eightfold Path.

The unwholesome roots are replaced by wholesome ones; as progress is

made and the end of the Path is reached, the Saints have neither

unwholesome nor wholesome roots, theirs actions are kammically

inoperative, and this is the summum bonum of the Dhamma.

Delusion

This striving is by no means easy. The Buddha was realistic about

this. In verse 239 of the Dhammapada, it is stated: “By degrees, little

by little, from time to time, a wise person should remove his own

impurities, as a smith removes (the dross) of silver” (Both Dhammapada

translations are by Ven. Narada). Confidence in the Threefold Refuge,

diligent application and patience will take the disciple along the Path.

What then is the cause of this delusion that a self or soul exists?

It is purely subjective, born of ignorance and nourished by the roots,

both unwholesome and wholesome. It is lack of insight into the most

profound statement ever made, that “bare phenomena roll on.” There is no

doer but only the action, there is no speaker but only the utterance,

there is no thinker but only the thought.

www.accesstoinsight.org

Going forth with meditation

Dr Padmaka Silva

If one becomes aware that ‘this is the path to Nibbana’ will his fear

leave him or will it increase? It leaves him. He becomes fearless. With

the fear leaving him joy will arise in him. He will become relaxed.

Thereafter he develops the skill to practice the meditation diligently.

Therefore we should try to develop an admiration for Satipatthana. We

should develop a liking for it. We should attempt to do so.

What have we got to do in this connection? We should develop a liking

to associate with worthy friends. We should attempt it. If we form an

association with worthy friends in that manner, it becomes possible for

us to form an admiration for Satipatthana.

|

|

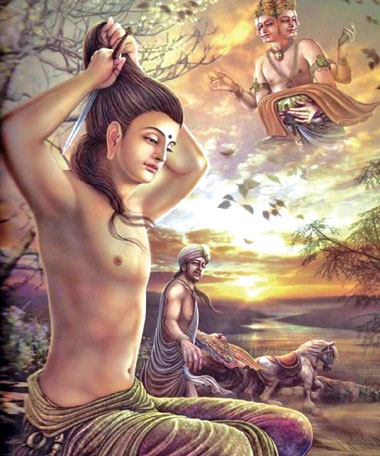

Meditation

leads to inner serenity |

A person who starts admiring the Satipatthana remains with a happy

mind. He lives with a fresh mind. His life is beautiful. The ugly nature

of life starts leaving him. The immense fear he had in Sansara starts

getting away from him. That is a natural phenomenon. There is nothing

strange in it. It is not a delusion. It is something that takes place.

All of us should get to like to arrive there.

The Buddha explained to us that this is the only path. Satipatthana

is the only way to develop purity in the mind, to remove suffering and

sorrow, to get rid of the nature of sadness and repentance in the mind,

to develop the unique wisdom and to attain Nibbana. Try to generate

confidence in this principle. Then there fearlessness will rise. Doubts

will disappear. Luke warmness in the mind will go off. Laziness will

leave you. Such a person will be able to live in joy.

If we form an admiration for Satipatthana for what has it been

formed? In respect of what was admiration formed? It was for the path to

Nibbana. We are in admiration of the Fourth Noble Truth. If one admires

one Noble Truth he gets to admire all Four Noble Truths.

One who develops admiration for Satipatthana develops admiration for

the four Noble Truths. If there is admiration for the Noble Truths isn’t

Saddha there? That means he has now arrived at Saddha.

That is if we develop an admiration or trust in Satipatthana we would

have made a great achievement. Therefore we should not perform useless

activities like blind people groping in the dark. Blind people will feel

here and there and say ‘What is this? Where is it? Don’t do meaningless

things like that. In the manner of a person with good eye sight

distinguishing things in broad day light, try to generate trust in

Satipatthana which has been explained very clearly. Be willing to do so.

Reread it. Read and develop admiration for that Dhamma preached by the

Buddha. Remove from the mind ideas like ‘How is that? How is this?’etc.

Leave aside suspicion and doubt. When there is confidence in

Satipatthana doubts go off. Leave aside that nature of doubting. Trust

in this Dhamma. One who trusts does not get into a hurry. He performs it

with patience.

When he practices for sometime he becomes certain of what he has

trusted. At this stage if he had any doubt such doubts will gradually

start leaving him. If there was any Dhamma which he had trusted, he

becomes absolutely certain of such Dhamma. It becomes so confirmed that

another person will not be able to make it leave him.

At this stage doubt is annihilated. Doubt will never arise in him in

future. It is impossible to annihilate doubt in that manner while

retaining doubt. Can we annihilate doubt while retaining doubt? It is

impossible to annihilate doubt while keeping it with us.

To get rid of doubt or to annihilate doubt what have we got to do in

the first instance?

First of all we must leave aside doubt. That is having confidence.

Confidence in the Dhamma means leaving aside the doubt. Does doubt get

annihilated merely by believing in the Dhamma? No. Leave aside doubt

without doubting. Place confidence in Dhamma after leaving aside doubt.

Develop a confidence in Satipatthana thinking ‘This is what is

correct. This is the way’. Develop admiration. Thereafter he starts

practicing the Dhamma explained in Satipatthana.

What is the quality we should have to practice that Dhamma? We should

get rid of the doubt we had about the Dhamma. Will we practice it if

there is no trust in the Dhamma.

It is impossible to get even an iota of the expected results by

practicing while retaining doubt. One may say ‘Let us try and see’.

Will he get the results? He is testing. One can never get results

from Dhamma by testing. What is close to experimenting is doubt.

Therefore leave aside doubt.

Have confidence in the understanding (enlightenment) of the Buddha.

What is the nature of the person who believes in the Dhamma? He has

patience. What does he do with patience? He starts practicing the Dhamma

with patience. Then who is he? One who practices Dhamma? What happens to

a person when he practices something? As he practices he develops an

understanding about what he practices. He becomes certain about what he

practices. An understanding is generated in him. That is what is called

becoming certain. What did he have in him before practicing? Was there

an understanding? No. What was there earlier? A trust, a confidence was

there. He believes in the Dhamma. After believing he practices it with

patience. What develops when he practices in that manner? When he

practices he develops in himself an understanding about it. What is it

called? Certainty.

It gets confirmed in himself. He becomes certain that it is the

truth.

After some time we develop a perfect confidence about what we

trusted. On that day doubt gets completely eradicated. It never comes

back. All this happens during meditation. It happens by improving the

mindfulness. To develop mindfulness we have to generate mindfulness. On

what should we generate mindfulness? On Satipatthana. If one has trust

in Satipatthana based on it he will improve the mindfulness. Then he

will be able to develop unshakable admiration for the Noble Truths.

We hope to talk about it in the future. May you get the fortune and

the strength to develop a strong admiration in respect of the Four

Satipatthana, the way to Nibbana shown by the Buddha. For that we bless

you to get the strength and the fortune to come across the association

with worthy friends, to develop it and to maintain it.

(Compiled with instructions from Ven Nawalapitiye Ariyawansa Thera.)

[email protected]

|