|

Buddhist Spectrum

Introduction to Digha Nikaya

Sudath Liyanage

The Digha Nikaya (dighanikaya; "Collection of Long Discourses") is a

Buddhist scripture, the first of the five nikayas, or collections, in

the Sutta Pitaka, which is one of the 'three baskets' that compose the

Pali Tipitaka of Theravada Buddhism. Some of the most commonly

referenced suttas from the Digha Nikaya include the Maha-parinibbana

Sutta (DN 16), which described the final days and death of the Buddha,

the Sigalovada Sutta (DN 31) in which the Buddha discusses ethics and

practices for lay followers, and the Samaññaphala (DN 2), Brahmajala

Sutta (DN 1) which describes and compares the point of view of Buddha

and other ascetics in India about the universe and time (past, present,

and future); and Potthapada (DN 9) Suttas, which describe the benefits

and practice of samatha meditation.

The Digha Nikaya consists of 34 discourses, broken into three groups:

Silakkhandha vagga:

The Division Concerning Morality (suttas 1-13); named after a tract

on monks' morality that occurs in each of its suttas (in theory; in

practice it is not written out in full in all of them); in most of them

it leads on to the jhanas (the main attainments of samatha meditation),

the cultivation of psychic powers and becoming an arahant

Maha vagga: The Great Division (suttas 14-23)

Patika vagga: The Patika Division (suttas 24-34)

The individual sutta breakdown

Brahmajala Sutta: mainly concerned with 62 types of wrong view

Samannaphala Sutta: King Ajatasattu of Magadha asks the Buddha about

the benefits in this life of being a samana (most often translated as

"recluse"); the Buddha's main reply is in terms of becoming an arahant

by the path outlined above

|

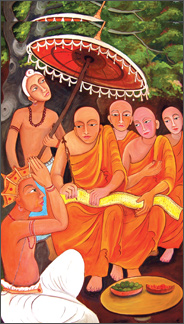

Establishment of the Thripitaka. Painting by Sudu Menike

Wijesuriya |

Ambattha Sutta: Ambattha the brahmin is sent by his teacher to find

whether the Buddha possesses the 32 bodily marks, but on arrival he is

rude to the Buddha on grounds of descent; the Buddha responds that he is

actually higher born than Ambattha and that society treats aristocrats

like himself as higher ranking than brahmins, but that he considers

those fulfilled in conduct and wisdom as higher, and he explains conduct

and wisdom as above.

Sonadanta Sutta: the Buddha asks Sonadanda the brahmin what are the

qualities that make a brahmin; Sonadanda gives five, but the Buddha asks

if any can be omitted and beats him down to two, morality and

wisdom,which he explains as above

Kutadanta Sutta: Kutadanta the brahmin asks the Buddha how to perform

a sacrifice (Rhys Davids considers this an example of a peculiar

straight-faced sort of humour to be found in texts such as this); the

Buddha replies by telling of one of his past lives, as chaplain to a

king, where they performed a sacrifice which consisted of making

offerings, with no animals killed; Kutadanta asks whether there are any

better sacrifices, and the Buddha recommends in succession going to the

Three Refuges, taking the Five Precepts and the path as above

Mahali Sutta: in reply to a question as to why a certain monk sees

divine sights but does not hear divine sounds, the Buddha explains that

it is because of the way he has directed his meditation; he then reports

the following sutta

Jaliya Sutta: asked by two brahmins whether the soul and the body are

the same or different, the Buddha describes the path as above,and asks

whether one who has fulfilled it would bother with such questions

Kassapa Sihanada Sutta, Maha Sihanada Sutta (maha-) or Sihanada Sutta;

the word sihanada literally means lion's roar: this discourse is

concerned with asceticism

Potthapada Sutta: asked about the cause of the arising of sañña,

usually translated as perception, the Buddha says it is through

training; he explains the path as above up to the jhanas and the arising

of their perceptions, and then continues with the first three formless

attainments; the sutta then moves on to other topics, the self and the

unanswered questions

Subha Sutta: Ananda explains the path as above

Kevaddha Sutta or Kevatta Sutta: Kevaddha asks the Buddha why he does

not gain disciples by working miracles; the Buddha explains that people

would simply dismiss this as magic and that the real miracle is the

training of his followers

Lohicca Sutta: on good and bad teachers

Tevijja Sutta: asked about the path to union with Brahma, the Buddha

explains it in terms of the path as above, but ending with the four

brahmaviharas; the abbreviated way the text is written out makes it

unclear how much of the path comes before this; Professor Gombrich has

argued that the Buddha was meaning union with Brahma as synonymous with

nirvana

Mahapadana Sutta: mainly telling the story of a past Buddha up to

somewhat after his enlightenment; the story is similar to that of "our"

Buddha

Maha Nidana Sutta: on dependent origination

Maha Parinibbana Sutta: story of the last few months of the Buddha's

life, his death and funeral and the distribution of his relics

Mahasudassana Sutta: story of one of the Buddha's past lives, as a

king; the description of his palace has close vebal similarities to that

of the Pure Land, and Dr Rupert Gethin has suggested this as a precursor

Janavasabha Sutta: King Bimbisara of Magadha, reborn as the god

Janavasabha, tells the Buddha that his teaching has resulted in

increased numbers of people being reborn as gods (according to the

Buddhist scriptures, Bimbisara was a Buddhist, but the Jain scriptures

say he was a Jain)

Maha-Govinda Sutta: story of a past life of the Buddha

Mahasamaya Sutta: long versified list of gods coming to honour the

Buddha

Sakkapanha Sutta: the Buddha answers questions from Sakka, ruler of

the gods (a Buddhist version of Indra)

Maha Satipatthana Sutta: the basis for one of the present-day Burmese

vipassana meditation traditions; many people have it read or recited to

them on their deathbeds

Payasi Sutta or Payasi Rajanna Sutta: dialogue between the sceptical

prince of the title and a monk

Patika Sutta or Pathika Sutta: a monk has left the order because he

says the Buddha does not work miracles; most of the sutta is taken up

with accounts of miracles the Buddha has worked

Udumbarika Sihanada Sutta or Udumbarika Sutta: another discourse on

asceticism

Cakkavatti Sihanada Sutta or Cakkavatti Sutta: story of humanity's

decline from a golden age in the past, with prophecy of eventual return

Agganna Sutta: another decline story

Sampasadaniya Sutta: Sariputta praises the Buddha

Pasadika Sutta: the Buddha's response to the news of the death of his

rival, the founder of Jainism, covering various topics

Lakkhana Sutta: explains the actions of the Budha in his previous

lives leading to his 32 bodily marks; thus it describes practices of a

bodhisattva (perhaps the earliest such description)

Singalovada Sutta, Singala Sutta, Singalaka Sutta or Sigala Sutta:

traditionally regarded as the lay vinaya

Atanatiya Sutta: gods give the Buddha a poem for his followers, male

and female, monastic and lay, to recite for protection from evil

spirits; it sets up a mandala or circle of protection and a version of

this sutta is classified as a tantra in Tibet and Japan

Sangiti Sutta: L. S. Cousins has tentatively suggested that this was

the first sutta created as a literary text, at the Second Council, his

theory being that sutta was originally a pattern of teaching rather than

a body of literature; it is taught by Sariputta at the Buddha's request,

and gives lists arranged numerically from ones to tens (cf. Anguttara

Nikaya); a version of this belonging to another school was used as the

basis for one of the books of their Abhidharma Pitaka

Dasuttara Sutta: similar to the preceding sutta but with a fixed

format; there are ten categories, and each number has one list in each;

this material is also used in the Patisambhidamagga

On right speech - Part II

Abhaya Sutta: to Prince Abhaya:

Thanissaro Bhikkhu

Now at that time a baby boy was lying face-up on the prince's lap. So

the Blessed One said to the prince, "What do you think, prince: If this

young boy, through your own negligence or that of the nurse, were to

take a stick or a piece of gravel into its mouth, what would you do?"

"I would take it out, lord. If I couldn't get it out right away, then

holding its head in my left hand and crooking a finger of my right, I

would take it out, even if it meant drawing blood. Why is that? Because

I have sympathy for the young boy."

"In the same way, prince:

[1] In the case of words that the Tathagata knows to be unfactual,

untrue, unbeneficial (or: not connected with the goal), unendearing and

disagreeable to others, he does not say them.

[2] In the case of words that the Tathagata knows to be factual,

true, unbeneficial, unendearing and disagreeable to others, he does not

say them.

[3] In the case of words that the Tathagata knows to be factual,

true, beneficial, but unendearing and disagreeable to others, he has a

sense of the proper time for saying them.

[4] In the case of words that the Tathagata knows to be unfactual,

untrue, unbeneficial, but endearing and agreeable to others, he does not

say them.

[5] In the case of words that the Tathagata knows to be factual,

true, unbeneficial, but endearing and agreeable to others, he does not

say them.

[6] In the case of words that the Tathagata knows to be factual,

true, beneficial, and endearing and agreeable to others, he has a sense

of the proper time for saying them. Why is that? Because the Tathagata

has sympathy for living beings."

"Lord, when wise nobles or priests, householders or contemplatives,

having formulated questions, come to the Tathagata and ask him, does

this line of reasoning appear to his awareness beforehand - 'If those

who approach me ask this, I - thus asked - will answer in this way' - or

does the Tathagata come up with the answer on the spot?"

"In that case, prince, I will ask you a counter-question. Answer as

you see fit. What do you think: are you skilled in the parts of a

chariot?"

"Yes, lord. I am skilled in the parts of a chariot."

"And what do you think: When people come and ask you, 'What is the

name of this part of the chariot?' does this line of reasoning appear to

your awareness beforehand - 'If those who approach me ask this, I - thus

asked - will answer in this way' - or do you come up with the answer on

the spot?"

"Lord, I am renowned for being skilled in the parts of a chariot. All

the parts of a chariot are well-known to me. I come up with the answer

on the spot."

"In the same way, prince, when wise nobles or priests, householders

or contemplatives, having formulated questions, come to the Tathagata

and ask him, he comes up with the answer on the spot. Why is that?

Because the property of the Dhamma is thoroughly penetrated by the

Tathagata. From his thorough penetration of the property of the Dhamma,

he comes up with the answer on the spot." 2

When this was said, Prince Abhaya said to the Blessed One:

"Magnificent, lord! Magnificent! Just as if he were to place upright

what was overturned, to reveal what was hidden, to show the way to one

who was lost, or to carry a lamp into the dark so that those with eyes

could see forms, in the same way has the Blessed One - through many

lines of reasoning - made the Dhamma clear. I go to the Blessed One for

refuge, to the Dhamma, and to the Sangha of monks. May the Blessed One

remember me as a lay follower who has gone to him for refuge, from this

day forward, for life."

www.accesstoinsight.org

Full awareness

Lotus Heart

After ten years of apprenticeship, Tenno achieved the rank of Zen

teacher. One rainy day, he went to visit the famous master Nan-in. When

he walked in, the master greeted him with a question, “Did you leave

your wooden clogs and umbrella on the porch?”

“Yes,” Tenno replied.

“Tell me,” the master continued, “did you place your umbrella to the

left of your shoes, or to the right?”

Tenno did not know the answer, and realized that he had not yet

attained full awareness. So he became Nan-in’s apprentice and studied

under him for ten more years.

This story just goes to show you how little we pay attention to the

things we do. It also makes me realize how much of my time is wasted by

paying little attention to what I am doing at each moment. I’m either

focused on the past or future and am not aware of what I’m doing.

Do we remember every detail of our day? Is it possible to be aware at

all times? Full awareness includes even the most insignificant things...

Sounds very odd, doesn’t it?

It’s funny how people do things without realizing that they’re doing

them. If you are a cashier at a convenience store you will notice this:

when you ask people what kind of sandwich they bought, they forget and

have to look down to read the wrapper.

Full awareness or great retention? Awareness should flow and not get

caught up in what flows through it. Memory isn’t attention. Doesn’t it

involve getting caught up in the flow?

How many experiences do we let slip by us in life? It’s scary to

think about.

Sometimes we may think we know or are aware of everything, but

someone else comes along to show us that we still have much to learn. No

matter how much you know, there is always someone who can teach you

more.

Whenever you are absolutely sure you are doing something right, it

turns out that you are going about it entirely the wrong way.

his story is not so inspiring, frankly! He’s not aware of where he

put his umbrella, so he lacks full awareness?! Maybe he was just focused

on other things at the time! I felt very frustrated and sorry for Tenno.

He feels he has been wasting his time, so he has to study for another 10

years, what a headache!

I think it sucks that the poor dude has to study for another 10

years. Of course, these are dedicated people, so it’s probably good for

them.

It’s my opinion that an adult can never obtain full awareness, unless

he or she is reared from parents with this developed state of mind.

Maybe I should give it a try after I get back from the all these worldly

things, ha!

He really must have felt he was wrong in his forgetfulness if he was

willing to lower himself and study for another ten years!

I think this story is a spoof of Zen practice, like any other Zen

story. People will take it too serious, for sure, but they have no clue

how to learn a lesson from that. The story stresses on the period, but

not ways and means of obtaining full awareness. |