Cultural orthodoxy and popular Sinhala music

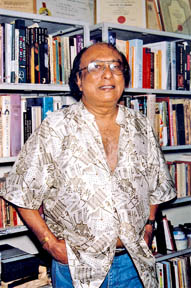

Dr. Tissa Abeysekara

Culture: This is an English version of the Convocation Address

delivered in the afternoon session of the First Convocation of the

University of Visual and Performing Arts, Colombo, held at the BMICH, on

August 04, 2007.

|

Art cannot be evaluated or interpreted in terms of culture |

The creative act, if it is to be genuine, could never be part of a

cultural agenda. A work of art is never born out of a desire to enrich

culture. This may happen in time to come after the product comes into

existence, but not by any conscious design at the moment of its origin.

Culture is an evolutionary process, and in that evolution, which is a

ceaseless progression, there is integration and rejection. Those that

are integrated become part of that culture. It is only then that they

qualify to be artifacts. But that takes time. Art, or the products of

creative enterprise therefore, can never be weighed and considered, nor

evaluated or interpreted in terms of culture.

There are those, and they are of every country and every age, who

attempt to codify culture. They presuppose that culture is an unchanging

matrix to be officially determined, and then perpetuated, promoted, and

protected as something inviolate. Culture as defined by these mandarins

is an entrenched clause in the constitution of public life.

|

Dr. Tissa Abeysekara |

In such sad circumstances, art becomes the first victim. The total

and unconditional freedom required for the meaningful exercise of the

creative act is withdrawn. Such mandarins are referred to in Sinhala

colloquial parlance as ‘Pothe Guras’.

This has to be explained even briefly, because that term encodes an

important attitude in our public life towards art and social morality.

The term ‘Pothe Gura’ refers to the Narrator in the folk theatre form

called ‘Nadagam’ which comes from the Tamil word Nattakoothu’. He reads

from a prescribed text, which never changes from performance to

performance. It is a fixed libretto.

Tradition

Performance, in the popular tradition of Eastern art, or perhaps even

in the West before certain recording mechanisms came into existence, was

always live, improvisatory, and never to be repeated in a fixed and

prescribed form. A vocalist singing a raag always improvises like a jazz

musician and his recitation can never be recollected and repeated note

by note.

Therein lies the magic of performance; non-duplicative and one of its

kind; hence the note of sarcasm when someone is referred to as ‘Pothe

Gura’. He is a pedant, a man with no originality, one who lives off

texts, and therefore with no imagination; a fossil, out of step with

living reality.

Of all the expressions which sensor the shifts in public and

collective taste, dress codes or fashions and music come first. In the

drift towards a global order transcending barriers of culture and

language what better symptoms are there than the denim and the guitar.

Originating in the rock culture of the late fifties, when Bill Haley and

his Comets and then the Elvis Presley phenomenon burst upon the music

scene, the guitar became the sound of youth all over the world.

George Harrison of the Beatles was yet to try plucking the sitar, and

Ravi Shanker had still not completely won over the west, but it was a

time when the introverted musical systems of the world were opening out

towards each other.

A synthesis between eastern and western musical forms had already

been achieved at a very basic level by the film musicians of Bombay and

Madras. Listen to the songs of Naushad Ali in the Bombay films of the

forties, like “Babul”, “Deedar” and “Dastan” and the hybrid

orchestrations of the composer Papanesan Sivam for the phenomenally

popular Tamil movie, “Chandralekha” and you could hear a veneer of

western musical flavour in the orchestration, and in the melody lines,

the vertical forms of western melodic structures.

Rhythms

Latin-American and Caribbean rhythms popularised during the war years

by musicians like Xavier Cugat and Perez Prado were seeping in too. This

drift in the popular music of India had begun much earlier in the kitsch

of the Parsee theatre of Bombay (Mumbai) and perhaps in a subtler and

more tasteful manner in the innumerable compositions of Rabindranath

Tagore collectively referred to as Rabindra Sangeeth.

There were two immensely popular melody makers, Rai Chand Boral and

Khemchand Prakash who continued this hybrid genre in Indian films of the

mid thirties. However, it was after the war and especially in the

fifties that the drift gathered momentum.

Curiously, this was precisely the time that the musical practice in

Sri Lanka - Ceylon then - was being locked through official policy into

a closed circuit.

The story which I am trying to recount today, begins with the

infamous Ratanjankar Audition, whereby a reputed scholar of Indian

classical music was brought down by the authorities to audition and

grade Sinhala vocalists. This was in 1952, and the move was strongly

contested by a powerful segment of the Sinhala music community, headed

by the most popular and leading composer/singer at the time, the now

legendary Sunil Shantha.

The background to this episode could be reconstructed from references

in the Administrative Reports of the Director General of Broadcasting at

the time, M.J. Perera. In his report dated May 1953 for the year of

review 1952, under the chapter on Broadcasting, the Director General

makes the following statement:

“During the year under review the most important event that took

place in the Sinhalese Section was the re-auditioning of artistes by

Professor S.N. Ratanjankar from Bhatkande University. His visit aroused

a good deal of controversy among musicians”.

Controversy

The Sinhala newspapers of this period are full of this controversy.

Reading them it is quite clear the majority of Sinhala musicians of

the time did not approve of this audition. Why was it held in the teeth

of such opposition? Who decided to get down Professor Ratanjankar? Who

took the decision to go head with it amidst such controversy? If the

majority in the Sinhala music establishment were campaigning vehemently

against the audition, as the newspapers so clearly indicate, whose

interests did it serve? There is no Sessional Paper tabled in Parliament

on the matter.

This means getting down the Indian specialist was not part of any

specific governmental policy, nor did it seek any such sanction. It is

then safe to conclude the decision was purely a matter of internal

administration of the Department of Information, and more specifically

of Radio Ceylon.

There is a clue however, in a letter M.J. Perera wrote to the CDN of

Tuesday, June 18, 1991, reacting to certain observations I had made on

this issue in a series of articles I wrote to the same paper on the

career of Sunil Shantha , and how it was terminated tragically by the

reactionary policies of the Sri Lankan musical establishment.

“The recommendation could,” says Perera in his article, “quite

possibly have come from the Sinhala Programmes Advisory Committee”.

Re-graded

Going by his own circulars and administrative reports I have had the

opportunity to peruse in the seventies, Perera shows much official

enthusiasm for implementing the recommendations of this Advisory

Committee.

In a book published by Dr. Nandana Karunanayake in the late nineties,

“Broadcasting in Sri Lanka - Potential and Performance” there occurs

this observation: Professor Ratanjankar re-graded the artistes on the

basis of auditions conducted by him.

M.J. Perera was instrumental in inviting Professor Ratanjankar and

took unusual interest in and commitment to improving the quality of

Sinhala music”. (Chapter 11/P. 291)

Great passion

It is important to note that among the members of this Advisory

Committee for Sinhala programmes, were Professor Ediriweera

Sarachchandra and Lionel Edirisinghe, two of the most ardent champions

of North Indian classical music.

The latter became the first Head of the Government School of Music,

newly constituted as a section of the Government College of Fine Arts,

in 1952. Professor Sarachchandra’s great passion for the Raaghadari

tradition of music is too well known to be elaborated here.

In 1952, the same year of the Ratanjankar Audition, Radio Ceylon

announced the formation of a station orchestra, and it was conditional

that henceforth all recordings both vocal and instrumental, for

broadcast use this orchestra. What is of special relevance to the point

I wish to make, is the instrumental composition of this orchestra.

In the 1952 November issue of the Radio Times, the official magazine

of Radio Ceylon, there is the following item boxed and displayed

prominently in its front page.

“The members of the Sinhalese orchestra and their instruments are:

Edwin Samaradiwakara(Leader), sitar, esraj, sarode, tarshenai, and

allied instruments; Sadananda Pattiarachchi, esraj, dilruba and tabla;

A.J. Careem, Clarinet; Edward de Silva, Tampura, tabla and kole; D.D.

Danny, flute; J.A.E Perera, tabla; M.A. Piyadasa, Violin; Ibrahim Sally,

drums (dholak, tabla taang, kole)”

Comment

In his article in the Ceylon Daily News, referred to, before, M.J.

Perera, makes the following comment: “The orchestra was not very large

at the outset and only the essential instruments could be accommodated.

” It is clear then that, those considered “essential instruments”

were, with the exceptions of the violin and the clarinet, exclusively

those of the Indian musical tradition.

It is a clear reflection of the thinking behind the steps taken by

the authorities, for, what they claimed to be, ‘the development of

Sinhala music.’ This was to confine Sinhala music to an exclusively

Indian base.

This policy was once again very specifically stated by M.J. Perera in

an Administrative Report on Broadcasting for the year 1954, submitted by

him in his capacity as Director General of Radio Ceylon.

“It was generally agreed that Sinhalese music is in need of greater

development and that more students should be encouraged to go to North

India for serious study. For this purpose it was suggested that the

Ministry of Education should offer scholarships annually for the study

of music in recognised institutions in North India.

To be Continued

|