Snakes and charmers

Snake charming is an art and a profession. It originated in India

where it was more or less a religious requirement. Before Hinduism,

snake worship was one of the ancient religions. Snake worship had

special temples and gods and deities. Hindus practiced the arts of

charming which included treating snake bite victims and herbal

treatments for various ailments.

|

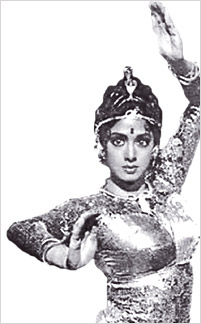

Indian women devotees offer prayers to a king cobra snake on the

occasion of Nagpanchami festival

in Bhopal |

Charming was a Hindu discipline but later other castes and groups in

Sindh, Bengal and Punjab also acquired this skill.

Along the Silk Route, which linked India, China and the

Mediterranean, traders exchanged silk, gold, emeralds, spices, ivory,

herbs and exotic animals; the snake was exotic for Westerners and

charmers were in demand. They entertained by enthralling snakes to the

sound of the been, sensuous sapera dances, fortune telling and also

dispensed medicinal herbs. Snake charming spread out of India to Turkey,

Persia, Sri Lanka and Nepal.

Saperas (snake charmers) are known as jogis (hermits). Often a hermit

leaves a city and finds abode in the forest, just like a sapera leaves

for the jungle to catch snakes. These days it is more of a trade and

often charmers go to known areas to catch or buy snakes.

Sapera villages

Tilla Jogian, near Jhelum, was a center where snake charmers from all

over India came to showcase their acts; a popular trick was putting a

snake in through the ear and pulling it out through the mouth; the

skilled jogi was adept and kept his secrets close to his chest.

At Tilla, charmers held an annual festival (mela) where Hindus and

Muslims performed snake acts. Guru Nanak spent time in meditation at

Tilla Jogian and his Urs became a part of the celebrations.

In pre-Islamic Swat, the snake was revered and its carved image

decorated Swati wooden pitchers. In the Kalash valley, snake carving is

found on pillars; the Kalash consider the snake a pure animal and deem

it godlike.

A snake both fascinates and repels. A feared reptile of the jungle,

it slithers and slides and disappears into holes, leaving people afraid

of its next peep into the outer world. An encounter with it fills one

with terror and awe. Its bite injects poison into the victim’s

bloodstream, paralyzing the vital organs of the body and taking away

life.

The cobra, majestic and indefinable, is deeply respected in India.

Buddhists believe a cobra spread its hood over the Buddha to protect him

from the sun while he meditated. The Hindu god Shiva is depicted with a

protective cobra coiled around his neck. The cobra is also seen as a sun

deity wielding power over rain, thunder, and fertility.

Saperas believe cobra is king: “Just as a Syed has status among

Muslims, so we consider black cobra (sheeshnag) highest among reptiles.”

|

Sapera is an ancient caste of snake charmers; the craft is passed

from one generation to the next. They live in settlements called sapera

villages; they speak their own dialect which uses words from local

languages. Street to street saperas perform snake shows. A sapera jogi

sits cross-legged on the ground in front of his closed basket. He

removes the lid and starts playing his been. As he plays and moves his

head from side to side, the snake turns and sways with the movement and

the spectator sees the snake mesmerized (mast). The sapera carries two

special items: the Geedar Singhi and the Manka, both of which customers

are eager to buy. The possessor of a Geedar Singhi (gland of a jackal)

is said to acquire money and fame; a Pathan uses the Geedar Singhi to

protect himself from bullets. Manka (a black stone-like thing found in

the head of the cobra) is said to cure snake bite and has magical

qualities; it is claimed that if an issueless woman drinks the water in

which a Manka was soaked, under a new moon, she will bear children. In

India, genuine Geedar Singhi and Manka are still available and well

preserved within families.

According to a Sindhi sapera: “We go to the desert and play our been

and hearing the flute the snakes come out of their holes.”

A snake’s ears are inside its mouth. It hears by vibrations

travelling through the ground; the inner ears rest on the earth and it

feels movement and vibes of sound travelling through the soil. It still

remains a mystery how snakes sense sound through vibrations; some say

the poised snake follows the movement, not the melody, of the been.

Charmers, however, have believed since olden times that a cobra responds

to certain musical tones and the primitive been is the fife it responds

to.

Been is a unique flute made from a gourd. The been gourd is shaped

like a globe with a long neck (one natural piece); two reeds are

attached to the dried gourd, one reed perforated to play melody and the

other for producing a drone. Been-playing requires circular breathing as

melodies do not allow for pauses; your breath has to keep going - you

push air out of the mouth and breathe in through nose, in this way

maintaining the flow. It creates a hauntingly sonorous music. Saperas

are masters of this long breath and only they can play the been; film

producers when they need been music in an orchestra summon the sapera.

A sapera shared his feelings about his been and music: “Saaz (musical

sound) is from the Beginning; the flute came later; saaz existed before

there was a flute.”

Saperas go snake catching in teams of three or four in all kinds of

weather. A sapera tames his snake by a simultaneous grasp of its head

and tail to assert himself as the master; he understands the nature of

each of his snakes and can tell its mood by the sound of the hiss. Also,

he talks to the snake to win its cooperation, “We promise our snake that

we won’t harm it and recite a verse to hypnotise it. ‘We swear on our

Murshid that we won’t harm you and will set you free (Qasam daitay hain

tujhe murshid ki kay tujhe maarengay nahin aur chhor daingay).’”

Saperas remove the snake’s venom but since every week the venom

glands create new poison they break the snake’s fangs so it cannot bite

to inject the venom. (The venom is sold separately to laboratories.)

Some saperas insist they do not remove venom but say to the snake, “For

love of Pir Goga do not bite!” and the snake obeys. Gogaji, a snake-king

devta, offers protection from snakes and other evils.

Healers and magicians

The professional art of snake charming is dying and charmers are

becoming a rare breed. In Pakistan it is dying because it does not pay.

Forty years ago charmers walked the streets and were invited into homes

and children and adults enjoyed the show. On Eid, saperas dressed in

long kurtas, coloured turbans, necklaces made of beads and shells, would

show up and perform with their beens and snakes.

A sapera said: “Sometimes people call us into their homes when we

pass by with the words “Baba Jogi Saanp Dekhao”, often homes with

children; and we play our been, show snake tricks to earn our bread. But

the enjoyment that people felt in the show (kartab) forty years ago is

not there. People dislike it now. Television in homes provides

entertainment; ordinary people’s temperament (mizaaj) has changed.”

In villages and small towns, charmers are often regarded as healers

and magicians and they concoct and sell potions and unguents: their

cures range from alleviation of the common cold to raising the dead!

Charmer women sell amulets and jewellery and handicrafts made of snake

skin and bones. The snake belongs to the wild even though saperas claim

their snakes are domesticated. They keep them in round baskets or clay

containers perforated for breathing. Snakes are not like other pets; the

saperas’ children are never allowed to play with snakes. Saperas do not

give their snakes names; they refer to them by breed, such as sheeshnag,

bandoya, chhota bandoya, bara bandoya.

While some sapera women are afraid to touch snakes, others will

handle them and move snakes from the sun into shade and open their

baskets to put water inside. Older children go hunting with their

fathers, dig holes to catch snakes and learn the profession.

For a sapera a naag (cobra) is his wealth - no naag, no wealth. He

explained: “It is just like a landlord (zamindar) is never satisfied and

is always looking to own more cattle. If we have ten snakes we go hunt

for the eleventh. Never enough!” A sapera never thinks of selling his

cobra; for him his reptile is priceless and the laboratory payment of Rs.

10,000 is paltry. He says, “The lab is concerned only about venom, not

breed. Cobra is of kingly ancestry and we respect that.”

A sapera philosophized: “In our search we often never go to the same

place again, we look forward to the next lake, next grove, jungle or

field to hunt for snakes. It is our livelihood and is all about this

stomach that is attached to us. Our lives are a ‘jogi wala phera’. Each

human has to do his round for his daily bread.”

Saperas marry within their clan; when looking for a match for his

daughter, a father’s concern is, “Is he a sapera and does he know the

art?” For his daughter’s dowry a sapera father must give a black cobra (sheeshnag)

else the girl’s in- laws will taunt her. A black cobra must be found by

the marriage date and the girl’s uncles and cousins all join in to hunt

for a naag. Other dowry essentials are Geedar Singhi and Manka.

Big black snakes like cobras and vipers are poisonous; many snakes,

however, are harmless. After biting its victim a snake is intoxicated

and faints and only moves after several minutes but people panic else

they could easily catch the snake.

Saperas say a cobra who has bitten a man is addicted to that bite;

there are man-eating snakes that wait for a man; a path becomes closed

and passersby are warned not to venture that way because the snake is

waiting.

It is popularly believed that if a cobra lives to be a hundred it can

take on any form. (‘Roop ichya tari.’) It enters the world of Jinns and

becomes supernatural.

If a sapera or his family member dies of a snake bite, there is

acceptance; it is God’s will and the person’s time had come; there is no

blame or bitterness for the snake.

In the ancient world the snake was an honoured symbol of medicine;

the Hippocratic Oath displays two snakes. The earliest snake charmers

were traditional healers by trade who as part of their business treated

snake bites and knew snake handling techniques and people called on them

to remove serpents from their homes.

Snake’s life

Snake characteristics, flexibility and speed, venom glands, shedding

of skin, made them attractive to healers. Flexibility suggested they

might be helpful in the treatment of stiffness, such as arthritis; their

speed in movement indicated their substance (in medicine) can move

quickly around the body, poison from glands is used for vaccination and

the fact that snakes shed their skin suggested a regenerative quality

beneficial for treating skin problems.

In Lahore, at Bhatti and Lohari gates, reptile oils are still sold

for everyday aches and pains; present-day hakims too use snakes for

various medicines.

In nature, snakes rest during the day and roam and hunt for food at

night. Snakes need very little food; there is an interval of many weeks

between their meals. They are carnivorous and eat frogs, rats, eggs,

fish, birds and insects; snakes swallow their food whole, as they cannot

tear or bite it apart.

Snakes occupy the holes of other reptiles as they are not able to dig

their own. Like the charmer, the snake is a gypsy and does not have a

permanent home! During breeding season the female snake gives off a

scent that brings the male to her. When old skin is outgrown snakes rub

against rough surfaces to shed it. If its snake cannot shed the snake

will die.

Cobras see very well, even at night, and can sense tiny changes in

temperature; they smell with their two-forked tongue in constant motion.

Their body picks up ground vibrations and snakes sense the approach of

other animals; the vibrations are felt along the length of their body.

Snakes are cold-blooded and hibernate for six months which gives them a

long life; one year of human life equals six months of a snake’s life.

There is a special ritual for acquiring power to heal snake bite

victim by prayer. A friend shared that she was passed the blessing (bakhsho’d)

by her aunt: the recipient had to be a five-times prayer observer. The

blessing is communicated under a moon eclipse. The recipient prays two

nafal, is given words (not Quranic words) to chant. The words are read

over a bowl of sugar followed by blessing sugar with a breath. When a

little bit of sugar is tasted by a bitten victim the effects of poison

dissipate and he becomes well.

My friend, the blessing recipient, was required at every solar and

lunar eclipse to pray two nafal, chant the secret words, add more sugar

to the original bowl and blow a breath on it. Eventually she gave up the

blessing gift as the ritual of maintaining it was too rigorous!

The snake has a special mention in two of man’s earliest texts: the

Book of Genesis and the Vedas. It is multifaceted - deemed holy and

godlike and also vile and satanic. It gives healing and also takes away

life; it is associated with wisdom, trickery, danger and magic. The

serpent carries messages and secrets and codes that are yet to be

fathomed.

Courtesy: The Friday Times

|