|

From Donne to Beethoven:

‘Music is a greater revelation than the whole of philosophy’

In our discussion last week (DN 19/9/12) of Eliot's theory of the

dissociation of sensibility in English poetry following Donne and Co.,

we noted that the principle seemed capable of application beyond the

scope of literature. Actually, the complementary observation made by

Yeats contained a clue to this effect, so here it is again: “In

literature.....we have lost in personality, in our delight in the whole

man - blood, imagination, intellect, running together - but have found a

new delight in essences, in states of mind, in pure imagination, in all

that comes to us most easily in elaborate music.” In our discussion last week (DN 19/9/12) of Eliot's theory of the

dissociation of sensibility in English poetry following Donne and Co.,

we noted that the principle seemed capable of application beyond the

scope of literature. Actually, the complementary observation made by

Yeats contained a clue to this effect, so here it is again: “In

literature.....we have lost in personality, in our delight in the whole

man - blood, imagination, intellect, running together - but have found a

new delight in essences, in states of mind, in pure imagination, in all

that comes to us most easily in elaborate music.”

What Yeats is implying here is that the condition of literature had

come to reflect a condition that already existed in elaborate

(presumably serious or classical) music. It was here that ‘essences,

states of mind and pure imagination’ were primarily in evidence. Yeats’

phrases, in fact, aptly described the music that was in vogue at the

time. Much of it tended to reflect ‘essential’ features of places,

characters and incidents; ‘states of mind’, moods, feelings and

passions; and experiences of a ‘purely imaginary’ or fantastic nature.

|

|

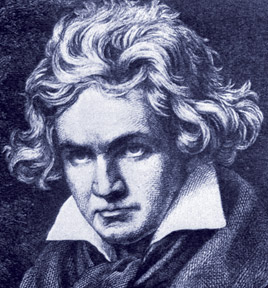

Beethoven |

Thus we have programme music such as Grieg's ‘Peer Gynt’ suite

(incidental music to Ibsen's play), and the symphonic poems of Liszt;

shorter and longer solo piano compositions like Chopin's ‘Nocturnes’ and

his ‘Fantasie-Impromptu’, (the pensive second subject of which was

adapted as the song, ‘I'm Always Chasing Rainbows’), and Schuman's

‘Scenes of Childhood’ incuding the famous ‘Traumerei'; and the

fairytale-telling ballet music of Tchaikowsky's ‘Sleeping Beauty,

‘Nutcracker’ and ‘Swan Lake’ suites These are just a handful of the wave

of predominantly emotional, pictorial and sensational music that swept

over the last two thirds of 19th century Europe and washed into the

early 20th.

Feelings and sentiments

Musical thinking or the thoughtful development of musical ideas was

little in evidence. Thus the musical experience provided did not involve

the total personality, ‘the whole man.’ But in the music of Beethoven,

which had dominated the first third of the 19th century, we do not find

such an absence of thought. And if the emotional power of Beethoven's

music is greater than that of his 19th century successors, despite their

stressing feeling and sentiment, it is precisely because as much thought

went into the making of his music as feeling. This is why his music

generally provides a more full-bodied musical experience.

Symphonies

It could, in fact, be said that the place of Beethoven in Western

music corresponds to that of Donne in English poetry. Both possessed a

unified sensibility, an attribute which we can well understand in the

case of the poet thanks to Eliot's insights. In the case of the

composer, however, it needs further explanation if it is not to seem a

mere generalisation.

It is Beethoven's approach to musical form that brings about the

fusion of thought and feeling in his music. It is usual to say that

Beethoven revolutionised form, yet he did not disrespect, still less

abandon it. What he did was to realise the full potential of the musical

forms available to him by extending them to satisfy the demands of his

musical imagination. During a period of personal crisis Beethoven made

the statement that “music is a greater revelation than the whole of

philosophy”. Thus he underook musical composition with a fervour that

can only be described as religious. That is why his musical imagination

was so demanding; it was activated by the whole man -with, as Yeats

would say, blood, imagination, intellect running together.

Consider, for example, Beethoven's treatment of the dominant ‘sonata

form’, in which the first movements of symphonies, concertos, sonatas

and most chamber works were usually written. This involved two or more

themes or subjects which were first laid out, then developed and finally

recapitulated. This form had been perfected by Mozart and Haydn and was

characterised by the melodic and tonal confict between subjects that

gave a dramatic dimension to the movement.

In his early phase Beethoven was happy enough to continue this

tradition - although his distinctive personality was in evidence from

the start. Perhaps the best example of this is his Opus 37 piano

concerto of 1800/01. But from the Op.55 ‘Eroica’ symphony of 1803/4

onwards Beethoven was no longer content with the conventional treatment

of sonata form. His first themes became more arresting and challenging,

his secondary subjects more sharply contrasted and conflicting, thus

greatly intensifying the dramatic effect.

These musical ideas were then not simply decorated or elaborated in

the development section, they were explored at length with radical tonal

shifts or modulations that revealed unexpected depths and ranges of

meaning. The scoring or technique of expression too became more dynamic

through greater textural and rhythmic variety. And the recapitulation

provided its own share of surprises.

The point is that such extensive analysis and development of thematic

material involved intense thought and concentration. Musical ideas and

concepts had to be identified, understood and absorbed into the musical

fabric in such a way as to make melodic, harmonic, rhythmic and textural

sense; in other words, to provide the equivalent of the sensuous

apprehension of thought that characterised the poetry of Donne.

It is worth referring, in this connection, to Mellers’ observation

that with a couple of exceptions the music of Beethoven's middle period

rarely features ‘cantabile’ or song-like melody. This is because his

‘ratiocinative’ approach to composition, thinking and working out his

ideas, demanded a totality of expression in which melody could not

predominate over the other musical elements. Lyricism is only regained

in Beethoven's last period where the thought process has become less

agitated, even occasionally serene, albeit no less intense.

Schubert hero-worshipped Beethoven but it is with him that the

unification of sensibility we find in Beethoven begins to unravel.

Schubert's genius lay in song-melody; he was incapable of the sustained

thinking required for genuine thematic development.

Apart from its sheer lyrical beauty, what gives his music its great

appeal is the depth and variety of dynamics and texture that he learnt

from Beethoven and developed further. But with him the emphasis began to

fall on feeling, passion, sensation. Thereafter, it seems, composers

took such aspects of Beethoven's composite technique as appealed to them

and refined these to even greater heights but without his ‘intellectual’

power. Thus, for example, did Chopin develop the intricate pianistic

figuration of Beethoven's last sonatas and Lizst his prodigious piano

technique and tempestuous streak. Yet the musical experience they

provide is relatively shallow.

The feeling or sensibility in Chopin's famous Op. 10 No. 3 Etude,

(adapted as the once-popular song, ‘So Deep is the Night), is, however

soulful, slighter - dare I say, as Eliot said of Gray's Elegy, “cruder”

- than that of Beethoven's popular Bagatelle, ‘Fur Elise.’

Brahms was one who tried valiantly to stem the tide. He wanted in his

own way to emulate Beethoven, but his melodic gift was too great to

ignore and his imagination and intellect lacked Beethoven's profundity.

As the 19th century wore on the cultivation of ‘essences, states of mind

and pure imagination’ continued apace. National feeling further evoked

the spirit of place and the feeling of nostagia, as in the music of

Smetana. Tchaikowski undertook writing concertos and symphonies and

dazzled one and all with his splendidly romantic themes. But he

generally drew a blank when it came to developing and exploring these to

any significant extent, vide his illustrious First Piano Concerto.

Greatness

All this is not to say that this music lacked greatness. Much of it

was more aesthetically beautiful and emotionally affecting than that of

Beethoven. Schubert and Brahms move us immensely, so can Dvorak and

Elgar. But the musical experience they provide is rarely full-bodied,

affecting us to the depths of our being as Beethoven's can do.

It is relevant that Eliot was profoundly affected by the music of

Beethoven, particularly his last string quartets. For it was Eliot who

sought to regain a unified sensibility in his poetry and made the effort

to look beyond the heart into ‘the cerebral cortex, the nervous system

and the digestive tracts'.

Of course, Beethoven did not spring from nowhere. Behind him were the

great figures of Mozart and Bach. The latter's music was described by

Wagner as ‘the most stupendous miracle in all music'. In this sense

Bach's position in music corresponds to that of Shakespeare in

literature.

And the achievement of Mozart corresponds to that of Milton: the

difference being that the appeal of Milton has waned whereas that of

Mozart is undying. To compare Bach, Mozart and Beethoven with each other

would be a purely subjective exercise unless it were a comparison of

their respective styles. Their individual worth is simply incomparable.

But the trend in musical sensibility following Beethoven seemed to be

worthy of consideration, and one is grateful for the direction provided

by Eliot.

|