|

Buddhist Spectrum

The Law of Cause and Effect

Ven Piyadassi Thera

‘Dependent Origination’ - Paticca-Samuppada - is a basic teaching of

the Buddha Dhamma (Buddhism). The doctrine therein being so deep and

profound, it is not possible within the limited scope of this essay to

make an extensive survey of the subject. Based solely on the teaching of

the Buddha an attempt is made here to elucidate this doctrine, leaving

aside the complex details involved.

Scholars and writers have in various forms rendered this term into

English. ‘Dependent Origination’, ‘Dependent Arising’, ‘Conditioned

Co-production’, ‘Causal Genesis’. ‘Conditioned Genesis’ are some

renderings. Throughout this essay the term ‘Dependent Origination’ is

used. Dependent Origination is not a discourse for the unintelligent and

superficial, nor is it a doctrine to be grasped by speculation and mere

logic put forward by hair-splitting disputants. Hear these words of the

Buddha. Scholars and writers have in various forms rendered this term into

English. ‘Dependent Origination’, ‘Dependent Arising’, ‘Conditioned

Co-production’, ‘Causal Genesis’. ‘Conditioned Genesis’ are some

renderings. Throughout this essay the term ‘Dependent Origination’ is

used. Dependent Origination is not a discourse for the unintelligent and

superficial, nor is it a doctrine to be grasped by speculation and mere

logic put forward by hair-splitting disputants. Hear these words of the

Buddha.

‘Deep, indeed, Ananda,The attendant - disciple of the Buddha. is this

Paticca-Samuppada and deep does it appear. It is through not

understanding, through not penetrating this doctrine, that these beings

have become entangled like a matted ball or thread, become like munja

grass and rushes, unable to pass beyond the woeful states of existence

and ,sansara, the cycle of existence.’ Maha Nidhana Sutta. Digha N.

Those who fail to understand the real significance of this;

all-important doctrine mistake it to be a mechanical law of causality,

or, even a simple simultaneous arising, nay a first beginning of all

things, animate and inanimate. Be it remembered that there is no First

Cause with a capital ‘F’ and a capital ‘C’ in Buddhist thought, and

Dependent Origination does not attempt to dig out or even investigate a

first cause. The Buddha emphatically declared that the first beginning

of existence is something inconceivable Samyutta N., II. Anamatagga

Samyutta,. p. 179., and that such notions and speculations of a first

beginning may lead to mental derangementAnguttara N., IV. 77.. If one

posits a ‘First Cause’ one is justified in asking for the cause of that

‘First Cause;’ for nothing can escape the law of condition and cause

which is patent in the world to all but those who will not see.

Phenomena

According to Aldous Huxley, Those who make the mistake of thinking in

terms of a first cause are fated never to become men of science. But as

they do not know what science is, they are not aware that they are

losing anything. To refer phenomena back to a first cause has ceased to

be fashionable, at any rate in the West... we shall never succeed in

changing our age of iron into an age of gold until we give up our

ambition to find a single cause for all our ills, and admit the

existence of many causes acting simultaneously, of intricate corelations

and reduplicated actions and reaction.Ends and Means (London 1945), pp.

14, 15.

Let us grant for argument’s sake that ‘X’ is the ‘first cause’ Now

does this assumption of ours bring us one bit nearer to our goal, our

deliverance? Does it not close the door to it? Buddhism, on the other

hand, states that things are neither due to one cause (ekahetuka) nor

are they causeless (a-hetuka) the twelve factors of Paticca-Samuppada

and the twenty four conditioning relations (Paccaya) shown in the

patthana, the seventh and the last book of the Abhidhamma pitka, clearly

demonstrate how things are, ‘multiple-caused’ (aneka-hetuka); and in

stating that things are neither causeless nor due to one single cause,

Buddhism antedated modern science by twenty five centuries.

We see a reign of natural law-beginningless causes and effects-and

naught else ruling the universe. Every effect becomes in turn a cause

and it goes on for ever (as long as ignorance and craving are allowed to

continue). A coconut, for instance, is, the principal cause or near

cause of a coconut tree, and that very tree is again the cause of many a

coconut tree. ‘X’ has two parents, four grandparents, and thus the law

of cause and effect extends unbrokenly like the waves of the sea-ad

infinitum.

It is just impossible to conceive of a first beginning. None can

trace the ultimate origin of anything, not even of a grain of sand, let

alone of human beings. It is useless and meaningless to go in search of

a beginning in a beginningless past. Life is not an identity, it is a

becoming. It is a flux of physiological and psychological changes.

‘’There is no reason to suppose that the world had a beginning at

all. The idea that things must have a beginning is really due to the

poverty of our imagination.

Therefore, perhaps, I need not waste any more time upon the argument

about the first cause.’’ Bertram Russel, Why I am not a Christian, p. 4.

Instead of a “First Cause”, the Buddha speaks of Conditionality. The

whole world is subject to the law of cause and effect, in other words,

action and result. We cannot think of anything, in this cosmos that is

causeless and unconditioned.

Combination

As Viscount Samuel says: ‘There is no such a thing as chance. Every

event is the consequence of previous events; everything that happens is

the effect of a combination of multitude of prior causes; and like

causes always produce like effects. The Laws of Causality and of the

Uniformity of Nature prevail everywhere and always.’ Belief and Action,

Penguin Books, 1939, p. 16.

Buddhism teaches that all compounded things come into being,

presently exist, and cease (uppada, thiti and bhaďga), dependant on

conditions and causes. Compare the truth of this saying with that

oft-quoted verse of Arahat Thera Assaji,An Arahat is one who has cut

himself off from all fetters of existence (Sansara) and attained to

perfect purity aud peace through, comprehending the Dhmma, the Truth.

one of the Buddha’s first five disciples, who crystallized the entire

teaching of the Buddha when answering the questions of Upatissa who

later became known as Arahat Thera Sariputta.

His question was: ‘What is your teacher’s doctrine? What does he

proclaim?’

And this was the answer:

‘Ye dhamma hetuppabhava tesan hetun tathagato aha

Tesan ca yo nirodho evan vadi mahasamano.P. T. S. Mahavagga p. 40,

Whatsoever things proceed from a cause,

The Tathagata has explained the cause thereof,

Their cessation, too, He has explained.

This is the doctrine of the Supreme Sage P. T. S. Mahavagga p. 54,

Though brief, this expresses in unequivocal Words Dependent

Origination, or Conditionality.

Our books mention that during the whole of the first week,

immediately after His enlightenment, the Buddha sat at the foot of the

Bodhi tree at Gaya, experiencing the supreme bliss of Emancipation. When

the seven days had elapsed He emerged from that Samadhi, that state of

concentrative thought, and during the first watch of the nightFirst

watch: from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. middle watch: from 10 p.m, to 2 a.m. and

the last watch: from 2 a.m. to 6 a.m. thought over the Dependent

Origination in direct order thus: ‘When this exists, that comes to be;

with the arising of this, that arises, namely.. dependent on ignorance,

volitional formations; consciousness... and so on... Thus is the arising

of this whole mass of suffering.For the whole formula consisting of the

12 factors see the last pages of this essay.

Origination

Then in the middle watch of the night, He pondered over the Dependent

Origination in reverse order thus; ‘when this, does not exist, that does

not come to be; with the cessation of this, that ceases, namely; with

the utter cessation of ignorance, the cessation of volitional

formations... and so on... Thus is the cessation of this whole mass of

suffering.’

In the last watch of the night, He reflected over the Dependent

Origination both in direct order and reverse order thus; ‘When this

exists, that comes to be; with the arising of this, that arises. When

this does not exist, that does not come to be; with the cessation of

this, that ceases, namely; dependent on ignorance. volitional

formations... and soon... Thus is the arising of this whole mass of

suffering. But by the utter cessation of volitional formations... and so

on... Thus is the ending of this whole mass of suffering.Udana, p, 1.

One may justifiably be inclined to pose the question; Why did not the

Tathagata set forth the doctrine of ‘Dependent Origination’ in His first

discourseDhammacakka-pavattana Sutta Sanutta N., the sermon delivered to

the five ascetics, His erstwhile companions, at Saranath, Benares? The

answer is this; The main points discussed in that all-important sermon

are the four Noble Truths; suffering, its cause, its destruction, and

the way to the destruction of suffering, the Noble Eightfold Way. There

is no word in it about ‘Dependent Origination’; but he who understands

the philosophical and doctrinal significance of the Dependent

Origination certainly understands that the twelvefold Paticca-samuppada,

‘Dependent Origination’, both in its direct order (anuloma) and reverse

order (patiloma) are included in the four Noble Truths.

The Paticca-Samuppada in its direct order manifests the process of

becoming (bhava), in other words, the appearance of suffering (dukkha,

the first Truth); and how this Process of becoming or suffering is

conditioned (dukkha-samudaya, the second Truth). In its reverse order

the Paticca-Samuppada makes plain the destruction of this becoming

(dukkha-nirodha, the third Truth) and the cessation of conditions, or

the destruction of suffering (dukkha nirodha gamina patipada, the fourth

Truth).

To be continued

Meditation for daily life :

Sabba Loke Anabiratha Sanna - Part II

Dr Padmaka Silva

Start practicing it briefly. Sit comfortably, with the body erect.

Then the laziness in the body leaves you. Now realize “I am not seated”.

Close your eyes and realize where you are seated. Next become conscious

of your posture. Be well conscious of it. Understand well that you are

now seated on the floor. Now contemplate as follows:

This eye is impermanent. The eye that is impermanent and sorrowful

and is subject to change is not ‘I’. Not mine. Does not belong to me. It

is not my soul. The visual objects seen with the eye are impermanent.

The objects subject to change are not ‘I’. Not mine and not my soul.

This ear is impermanent. The ear that is impermanent and sorrowful

and is subject to change is not ‘I’. Not mine. Does not belong to me. It

is not my soul. This ear is impermanent. The ear that is impermanent and sorrowful

and is subject to change is not ‘I’. Not mine. Does not belong to me. It

is not my soul.

Soul

The sound heard with the ears are impermanent. The sound subject to

change are not ‘I’. Not mine and not my soul. This nose is impermanent.

The nose that is impermanent and sorrowful and is subject to change is

not ‘I’. Not mine. Does not belong to me. It is not my soul.

The smell felt with the nose is impermanent. The smell felt with the

nose is not ‘I’. Not mine and not my soul. This tongue is impermanent.

The tongue that is impermanent and sorrowful and is subject to change is

not ‘I’. Not mine. Does not belong to me. It is not my soul.

The taste felt with the tongue is impermanent. The taste felt with

the tongue is not ‘I’. Not mine and not my soul.

This body is impermanent. The body that is impermanent and sorrowful

and is subject to change is not ‘I’. Not mine. Does not belong to me. It

is not my soul.

The touch felt with the body is impermanent ///. The touch felt with

the body is not ‘I’. Not mine and not my soul. This mind is impermanent.

The mind that is impermanent and sorrowful and is subject to change is

not ‘I’. Not mine. Does not belong to me. It is not my soul. The objects

felt with the mind are impermanent. The objects felt with the mind are

not ‘I’. Not mine and not my soul.

Wish for the Samadhi to leave you. Now open the eyes.

As you keep on practicing it will be possible to carry out the

meditation fully. Therefore it will be possible to do it completely

after some time when you do it with effort without getting in to a

hurry. At the same time think of generating an aversion to eye, ear,

nose, tongue, body and mind.

Quiet

If we get used to thinking of our sense organs in this manner don’t

we become quiet? Doesn’t the state of hurry get reduced? Why? We have

some work to do. Even if we are seated we are doing some work. We are

thinking of eye, ear, nose, tongue, body and mind wisely. No one knows

what we are doing. No one sees what we are doing. Don’t you now see that

one’s internal matters are not visible to anyone? There is nothing to

keep talking. There is no time to keep on talking about unnecessary

things. Thus things like loneliness, solitude do not come up. If one

gets used to this you can think of the sense organs while remaining

seated where you are.

We need not get into a hurry thinking that there is a big crowd. A

quiet environment gets built up effortlessly. We are doing a correct

thing with the mind. If we do something wrong with the mind the noise

starts again. When you keep on doing the correct things with the mind

your mind gets quenched. Becomes calm.

Unnecessary words do not come out of him. A large group can remain

together. Why? Because we generate dislike for the eye. We generate

dislike for the visible object also. We are thinking in a manner which

generates disgust.

When you are idling do not keep on talking unnecessary things. Think

of the reality of your life. Misery has arisen in our life due to this

eye, ear, nose tongue, body and mind. Raga causes the mind to burn. Dosa

and Moha also cause the mind to burn. Various tormenting fires arise in

the mind. Inconveniences arise in the mind. Torments arise. Humans live

in torment. That is misery. If you do not have mindfulness, if you do

not use wisdom you get overcome by these agonies and suffer further. You

cannot escape. When there is no wisdom there are two torments. If you

use wisdom you can think of getting rid of those torments while

experiencing those torments.

You think how those torments arose. Then you develop dislike for the

entities that caused the torments so that you can prevent their coming

up again. That is what is called using wisdom. Torments can be there for

everyone. Repentance can be there. The mind can catch fire. Do not get

excited at such times. Think as to who caused the fire or who caused

this sorrow. That thought can be generated with the help of the Dhamma

preached by Buddha. Buddha has explained to us that the sorrow has

arisen due to the eye. That knowledge is necessary. What we mentioned is

a way to adapt that knowledge of Dhamma to our life. By thinking so, the

delight in the entire world ceases. The adaption of the Dhamma to our

life occurs. That is how the Dhamma gets adopted to one’s life.

Can’t this be done while standing? Can’t it be done while walking,

seated or lying down? It can be done while being in any of these four

postures. If one gets used to this will his life become calm or

disturbed? Life becomes calm. When you do this will the fire get

quenched instantaneously? No. It does not get quenched immediately. When

one starts doing it the fire begins to get quenched. The nature of fire

starting again starts getting obliterated.

Objects

Therefore generate mindfulness well and think in the manner of

getting rid of the liking for this eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind,

visual objects, sounds, odors, tastes, touch and mind objects. A good

time to think in the manner of getting rid of this liking is when a

problem arises in mind. Then practice it. It can be practiced at other

times also. One is not inclined to do this when one is generally at

ease. When a discomfort arises, identify it and ponder on what

originated it. Any discomfort entering the mind is due to Raga, Dosa or

Moha. That is the fires of Raga, Dosa and Moha are caused by the sense

organs eye, ear, nose, tongue, body and mind. We must accept that fact

through the Dhamma.

We were not aware of such a thing. We cannot imagine how Raga arises

due to the eye. How do we know? Can we think of it? We cannot. Is it

taught at school? No. From where did we learn it? From Dhamma. If there

is confidence in what one learnt in Dhamma, when Raga arises he thinks

“This is what Buddha explained to us about its arising due to the eye”.

He can recollect that. That is how thinking with wisdom is associated

with Saddha. That is why Suttas have to be studied over and over again.

That is why Dhamma has to be listened to again and again.

Discussions

That is why we should participate in Dhamma discussions again and

again. When we listen to Dhamma again and again, participate in Dhamma

discussions frequently, if there is some Saddha in us it gets enhanced.

If there is some Saddha which has not arisen it arises. It arises and

gets completed. Based on that Saddha we can develop the thinking with

wisdom. If Dhamma comes to our mind when some mental agony comes up,

isn’t it due to Saddha. Will an individual without Saddha think of

Dhamma when a problem arises? No. Sometimes Dhamma might not come to our

mind when a problem comes up. But the worthy friend reminds you the

reason for the problem is this and to think in such and such a manner.

Can’t he then seek refuge in the Dhamma? That is the assistance we get

from Saddha.

The individual in whom Saddha has been generated can generate

Yonisomanasikara (thinking according to Dhamma) himself. Or he can do so

when the worthy friend reminds him. In order to achieve the benefits of

Dhamma, think of this life as indicated in the Dhamma. An appropriate

time for it is when torments and repentance arise. At such times think

as to how that torment arose. Compiled with instructions given by Ven

Nawalapitiye Ariyawansa Thera. [email protected]

Introducing Buddhism to the West

Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi

Olcott’s lectures profoundly inspired a young Sinhalese Buddhist from

a Colombo mercantile family named Don David Hewavitharana, who had

earlier attended sermons by Ven. Mohottiwatte Gunananda, the Panadura

orator. In 1884, at the age of nineteen, David joined the BTS and soon

became a favorite of Olcott and Blavatsky, who encouraged him to study

Pŕli and “to work for the good of Humanity.”

In 1885, Hewavitharana vowed to live as a brahmacŕră, a full-time

celibate, and took the name Anagŕrika Dharmapŕla. The word anagŕrika

means “homeless one” and traditionally described the state of a Buddhist

monk. Dharmapŕla, however, did not take formal monastic ordination but

committed himself merely to observing full-time celibacy so that he

could work more freely for the cause of Buddhism than a monk, restrained

by the rules of the monastic code, could do. In 1885, Hewavitharana vowed to live as a brahmacŕră, a full-time

celibate, and took the name Anagŕrika Dharmapŕla. The word anagŕrika

means “homeless one” and traditionally described the state of a Buddhist

monk. Dharmapŕla, however, did not take formal monastic ordination but

committed himself merely to observing full-time celibacy so that he

could work more freely for the cause of Buddhism than a monk, restrained

by the rules of the monastic code, could do.

Before long, Dharmapŕla became the most articulate spokesman for the

Sinhala Buddhist renaissance. His lectures and writings linked together

the themes of Buddhism, Sri Lankan nationalism, and Sinhalese ethnic

identity, in a way that motivated Sinhalese Buddhists to rediscover the

greatness of their ancient history, including its Buddhist heritage.

In 1891, Dharmapŕla visited the holy places of Buddhism in northern

India and found, to his dismay, that they were all in decrepit

condition. He was particularly disturbed at the condition of the

Mahŕbodhi temple at Bodhgaya, the site of the Buddha’s enlightenment,

which was then under the control of a Hindu priest. Having vowed to

struggle for the transfer of control over the temple to the Buddhists,

he founded the Mahŕbodhi Society, with branches in both India and Sri

Lanka, to support him in his work. He also commenced publication of a

Buddhist magazine, the Mahŕbodhi Journal (1892). We should remember that

it was for the Mahŕbodhi Society that Bhante G worked during his sojourn

in India.

Though his base was in India, Dharmapŕla regularly visited his home

country and his speeches and writings continued to exercise a strong

influence there and beyond.

In 1893, he attended the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago as

a representative of Theravŕda Buddhism. Here, Dharmapŕla argued

passionately against the claims of Christianity, defending Buddhism as

the religion of science and rationality. Perhaps most significant for

future trends, Dharmapŕla did not rest content merely calling for a

revival of Buddhism in its traditional lands and for a Buddhist

renaissance in India. Rather, he saw Buddhism as having a new universal

message for all humankind, and he called on the young Buddhists of Asia

to share this message with the world:

Young Buddhists of Asia! The time is come for you to prepare yourself

to enter the battlefield of Truth, Love and Service and carry the

message of Equality, Brotherhood, Compassion, Selflessness, Renunciation

to the energetic people of England, Germany, United States, France and

other countries.... These countries should know of the supreme Truths

promulgated by the Buddha, who taught them 2500 years ago to the most

enlightened people of Aryan India.... Let the People of these countries

know the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eightfold Path, the seven

Principles of Enlightenment, and the 12 bases of the Law of Causality.

This article was published in 1927. One could well imagine that the

mother of one “young Buddhist of Asia” who was to take birth towards the

end of that year had somehow heard Dharmapŕla’s speech and had vowed

that her son-to-be would one day convey “the supreme Truths promulgated

by the Lord Buddha” to the energetic people of the United States.

Sri Lanka gained its independence from Britain in 1948. Hardly eight

years later, a major milestone in Theravŕda Buddhism’s interpretation of

its own history was due to arrive: the 1956 Buddha Jayanti. This year

was to mark the 2500th anniversary of the Buddha’s parinibbŕna, the

theoretical midpoint of the “Buddha Sŕsana,” the full lifespan of

Buddhist history. For Sinhalese Buddhists, moreover, the Buddha Jayanti

meant the completion of 2500 years of Sri Lanka’s own history, which

according to tradition began with the arrival of Vijaya on the island at

the same time that the Buddha passed away.

While Buddhists generally understood the passage of time to bring a

gradual decline in the fortunes of Buddhism, popular belief held that

the halfway mark in the history of their religion was to be accompanied

by a worldwide Buddhist revival and the spread of the Dhamma to many

lands where it had never previously flourished. Within Sri Lanka,

Buddhist activists emphasized the need to restore Buddhism to its

“rightful place” in the life of the nation. The Sinhalese Buddhists,

both monks and laity, perceived themselves as a disadvantaged majority,

outranked by an English-educated Christian elite that gave a privileged

status to Christianity. But the Sinhalese Buddhists also believed that

the Buddha Jayanti provided an opportunity, not only to restore to

Buddhism the pristine glory that it had previously enjoyed within Sri

Lanka, but also to spread the light of the Dhamma all over the world.

They had already seen Buddhists from the West come to their country,

ordain as Buddhist monks, and achieve eminence in the Sangha. So there

seemed to be no reason why Buddhism could not be successfully propagated

in the Western countries themselves, with Sri Lanka as the source of

propagation. As one prominent Sinhalese Buddhist intellectual formulated

these hopes: “Buddhism will rise to great heights again and blossom

forth once more in Sri Lanka. From there it will spread all over the

world.”

One project taken up in connection with the Buddha Jayanti was the

sending of missionaries, or dhammadutas, to other countries. The idea of

setting up Buddhist temples in the West, however, hardly needed to be

inspired by the approach of the Buddha Jayanti. Already as far back as

1926 a Buddhist vihŕra or temple had been established in London, the key

figure behind this project being none other than Anagŕrika Dharmapŕla.

Through the years the London Buddhist Vihŕra has been occupied by

prominent Sri Lankan monks, among them Ven. Nŕrada Mahŕthera, Ven.

Saddhŕtissa Nŕyaka Thera, and Ven. Medagama Vajiragnŕna Nŕyaka Thera,

the present chief incumbent. Under the stewardship of the Anagŕrika

Dharmapŕla Trust, the Vihŕra continues to exist today in spacious

premises in Chiswick.

In 1952, the Colombo businessman Asoka Weeraratna founded the German

Dharmadĺta Society in the back room of his family shop, later moving it

to separate premises purchased with funds he acquired through a zealous

fund-raising drive. Weeraratna’s burning ambition was to promote the

spread of Buddhism in Germany and he saw the need to have a Buddhist

center right in the heart of Germany itself. Having searched for

suitable premises throughout Germany, he found the ideal site he wanted

in the lovely Frohnau district of Berlin. The place he discovered was

Das Buddhistische Haus, an old Buddhist compound built by the German

Buddhist pioneer Paul Dahlke in 1924. Under Weeraratna’s initiative the

German Dharmadĺta Society purchased the compound, renovated it, and in

1957 brought it back to life as the Berlin Buddhist Vihŕra. In the same

year, Asoka Weeraratna organized the first Buddhist mission to Germany,

led by three Sri Lankan bhikkhus whom he accompanied on their journey.

From that time to the present, the Berlin Vihŕra has helped to maintain

a Theravŕda presence in Germany.

When Sri Lankan-based vihŕras already existed in Britain and Germany,

the inevitable next target in the spread of the Sri Lankan monastic

missions to the West was the United States. To fulfill this mission was

the task taken up by Ven. Madihe Pannasiha Mahŕnŕyaka Thera, a highly

respected monk from the Vajirŕrŕma Monastery in Colombo. Vajirŕrŕma was

one of the elite monasteries that in the 1930s and 1940s had attracted

educated young men inspired by a reformist vision of Buddhism similar in

many ways to that preached by Anagŕrika Dharmapŕla, but with a much

softer and mellower flavor.

Its founder, Ven. Pelene Vajiragnŕna, was an erudite scholar-monk

highly respected among the educated classes in Colombo and its suburbs.

Though Ven. Vajiragnŕna did not speak English himself, he attracted

English-educated pupils who became known under such monastic names as

Nŕrada, Piyadassi, Bope Vinăta, and Ampitiye Rŕhula. Madihe Pannasiha

hailed from Matara, in the deep south, and was not fluent in English,

but he impressed his teacher and fellow monks with his erudition,

leadership qualities, innovative ideas, and concern for the protection

of Buddhist interests in the newly independent nation.

In the run-up to the Buddha Jayanti, he served on the Committee of

Inquiry charged with rectifying the grievances of the Buddhists. After

Vajiragnŕna’s death in 1955, he became the chief monk or Mahŕnŕyaka

Thera of the Amarapura Dharmarakshita Nikŕya, the monastic fraternity to

which Vajirŕrŕma belonged. In 1958, he established the Vajiragnŕna

Bhikkhu Training Centre near the town of Mahŕragama, a short distance

from Colombo, to train young monks in accordance with the traditions of

his teacher. In this endeavor he was supported by the affiliated lay

organization that he had created, the Sŕsana Sevaka Society.

In 1964, Ven. Pannasiha visited the U.S., accompanied by Olcott

Gunasekera of the Sasana Sevaka Society.6 While in Washington, D.C., the

two attended a Vesak celebration conducted in traditional Sri Lankan

style on the grounds of the Textile Museum, organized by Dr. Kurt F.

Leidecker, a scholar of Buddhism and professor of religious studies at

Mary Washington College, and Nimalasiri Silva of he Embassy of Ceylon

(then the name for Sri Lanka).

On their return to Sri Lanka, Ven. Pannasiha decided to establish a

Theravŕda vihŕra in Washington, the capital of the most powerful country

on earth. Together with Gunasekera, he formed a new branch of the

international service division of the Sasana Sevaka Society which was to

oversee the launching of the Washington Buddhist center.

They requested Ven. Bope Vinăta, another Vajirŕrŕma monk, to take

responsibility for the project. Ven. Vinăta had spent the past two years

studying at the Center for the Study of World Religions at Harvard

University and thus was familiar with the American social and

intellectual landscape. He had previously helped establish Buddhist

temples in Germany and Great Britain and therefore seemed eminently well

qualified for the job.

Ven. Vinăta accepted the assignment and departed for Washington,

taking along a Buddha statue and a relic of the Buddha. He arrived in

June 1965 and soon after moved into a first-floor apartment in an

apartment building on Harvard Street, in northwest Washington, which was

to serve as the first headquarters for the new vihŕra. On July 23rd,

soon after moving into the apartment, Ven. Vinăta held the inaugural

meeting of the fledgling Buddhist Vihŕra Society. At every step he was

given the full support of the Ceylon Government through its embassy in

Washington.

According to its constitution, Ven. Madihe Pannasiha, as the patron

of the Buddhist Vihŕra Society, was responsible for appointing the abbot

or “chief incumbent monk” of the vihŕra, who then by virtue of his

position as abbot became the president of the society.

Ven. Vinăta served as the abbot or “chief incumbent” of the vihŕra,

and first president of the Buddhist Vihŕra Society, until May 1967. In

that month Ven. Dickwela Piyananda Mahŕthera, a scholar-monk with a

specialization in Sanskrit literature, arrived. At the request of Ven.

Vinăta, Ven. Pannasiha appointed Ven. Piyananda the next abbot of the

vihŕra and thus the second president of the society. The two monks

continued to dwell in the “apartment vihŕra” on Harvard Street. But

earlier, in 1967, Ven. Vinăta and the Ceylon Embassy had arranged to

purchase from the Government of Thailand a house at 5017 16th Street NW

that the Thai Embassy had used as its education counselor’s office and

as a dormitory for Thai college students. Before the deal was completed,

in February 1968, Ven. Vinăta left the U.S. on account of ill health,

and Ven. Piyananda became the sole resident monk.

On May 26 of that year he moved to the building on Sixteenth Street,

which became the new home of the Washington Buddhist Vihŕra and the

first proper Theravŕda vihŕra in America.

But, with Ven. Vinăta gone, Ven. Piyananda needed a younger monk to

help him with his heavy burden of work. The Sasana Sevaka Society back

in Sri Lanka thus sent out feelers for a Sri Lankan monk who knew

English well, was interested in missionary work, and could adapt to the

sometimes difficult conditions that an Asian monk would have to face

when attempting to propagate the Dhamma in the West.

Courtesy: Preserving the Dhamma - Writings in

Honour of Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Maha Thera

Animals released

|

|

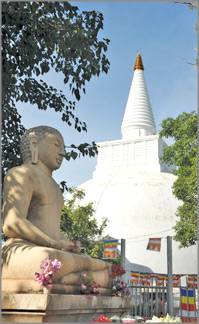

Eight cows and four goats have been

released to commemorate the four-month death anniversary of

L P Mahesh Pathmalal. The meritorious event took place at

Kuda Uduwa Sri Bodhimalu temple under the patronage of its

Chief Incumbent. Picture by Saliya Rupasinghe |

|