|

Buddhist Spectrum

The world of Buddhism: unity in diversity

Professor Y Karunadasa

Continued from December 22

In his well known discourse on the Parable of the Raft, the Buddha

compared his Dhamma to a raft. It is for the purpose of crossing over

and not to be grasped as a theory. The Dhamma has only instrumental

value. Its value is relative, relative to the realization of the goal.

|

|

The vision that inspired Professor G P

Malalasekara in establishing the World Fellowship of

Buddhists |

As an extension to this idea, it also came to be recognized that the

Dhamma as a means can be presented in many ways, from many different

perspectives. There is no one fixed way of presenting the Dhamma which

is valid for all times and climes. The idea behind this is that what is

true and therefore what conforms to actuality need not be repeated in

the same way as a holy hymn or a sacred mantra. The Dhamma is not

something esoteric and mystical. As the Buddha says, the more one

elaborates it, the more it shines (vivato virocati).

In connection with this, what we need to remember here is that the

Dhamma is not actuality as such. Rather, it is a description of

actuality. It is a conceptual-theoretical model presented through the

symbolic medium of language. There can be many such

conceptual-theoretical models depending on the different perspectives

one adopts in presenting the Dhamma. However, the validity of each will

be determined by its ability to lead us to the goal: from bondage to

freedom, from ignorance to wisdom, from our present human predicament to

full emancipation.

We find this situation beautifully illustrated in a Chinese Buddhist

saying that the Dhamma is like a finger pointing to the moon. This

analogy has many implications. One implication is that any finger can be

pointed to the moon. What matters is not the finger as such but whether

it is properly pointed so that we can see the moon. Another implication

is that if we keep on looking only at the finger we will not see the

moon. Nor can we see the moon without looking at the finger, either.

We can therefore approach different schools of Buddhist thought as

different fingers pointing to the same moon. If we approach them in this

manner then we need to identify their common denominator, the most

fundamental doctrine that unites them all? This is a matter on which we

don't have to speculate. For the Buddha himself as well as all schools

of Buddhist thought identify it as the Buddhist doctrine of the denial

of soul/self/ego (anatta).

From its very beginning Buddhism was fully aware that the doctrine of

the denial of soul was not shared by any other contemporary religion or

philosophy. We find this clearly articulated in an early Buddhist

discourse. Here the Buddha refers to four kinds of clinging: clinging to

sense-pleasures, clinging to speculative views, clinging to mere rites

and rituals in the belief that they lead to liberation, and the clinging

to the notion of self. The discourse goes on to say there could be other

religious teachers who would recognize only some of the four kinds of

clinging, and that at best they might teach the overcoming of the first

three forms of clinging. What they cannot teach, because they have not

comprehended this for themselves, is the overcoming of clinging to the

notion of self, for this, the last type of clinging, is the subtlest and

the most elusive of the group. The title given to this discourse is the

Shorter Discourse on the Lion's Roar. Clearly it is intended to show

that the Buddha's declaration of the denial of soul is "bold and

thunderous like a veritable lion's roar in the spiritual domain" (Ven.

Bhikkhu Nanamoli).

That the notion of no-self is the most crucial doctrine that

separates Buddhism from all other religions came to be recognized in the

subsequent schools of Buddhist thought as well. Acarya Yasomitra, a

savant of the Sautrantika School of Buddhism (5th c. C. E.)

categorically asserts: "In the whole world there is no other religious

teacher who proclaims a doctrine of non-self". We find this same idea

echoed by Acariya Buddhaghosa, the great commentator of Theravada

Buddhism when he says: "The knowledge of non-self is the province of

none but a Buddha" (Vibhanga Commentary, 5th c. C. E.).

If there is one doctrine which is unique to Buddhism, it is the

doctrine of non-self. If there is a doctrine which is unanimously

accepted by all Buddhist schools, whether they come under Theravada,

Vajrayana, or Mahayana, it is the doctrine of non-self. If there is a

doctrine which, while uniting all schools of Buddhist thought, separates

Buddhism from all other religions and philosophies, it is again the

doctrine of non-self.

The whole world of Buddhist thought is, in fact, a sustained critique

of the belief in self, the belief that there is a separate

individualized self entity which is impervious to all change.

If we can thus establish the transcendental unity of Buddhism on the

basis of the Buddhist doctrine of non-self, we can also establish it on

the basis of Buddhism's final goal as well. When Maha Pajapati Gotami,

the foster mother of the Buddha, wanted to know how one could separate

the Dhamma from what is not the Dhamma, the Buddha said: Whatever that

leads to the cessation of greed (raga), aversion (dosa), and delusion

(moha) is the Dhamma, and that whatever that leads away from it is not

the Dhamma. The Buddha compares greed, aversion, and delusion to three

fires with which the unenlightened living beings are constantly being

consumed. In point of fact, the final goal of Buddhism, which is

Nibbana, is not some kind of ineffable mystical experience, but to lead

a life free from greed, aversion , and delusion.

This, in fact, is the goal common to all schools of Buddhist thought,

although it came to be described in different ways and from different

perspectives.

What we have observed so far should show why what the Buddha taught

gave rise to a wide variety of Buddhist schools and interpretative

traditions in the continent of Asia. Another question that arises here

is why what the Buddha taught came to be communicated through many Asian

languages and dialects. Apart from the well known classical languages

such as Pali, Prakrit, Sanskrit, Chinese, Tibetan and Mongolian, in the

lost civilization of Central Asia alone Buddhist manuscripts in about

twelve indigenous languages have been discovered. The reason for this

"multi-lingualism" is that from its very beginning Buddhism did not

entertain the notion of a "holy language." In point of fact, when it was

suggested to the Buddha that his teachings should be rendered into the

elitist language of Sanskrit, the Buddha did not endorse it and enjoined

that each individual could learn the Dhamma in his/her own language

(sakaya-nirutti).

From the Buddhist perspective, thus, the Dhamma as well as the

language through which it is communicated, are both means to an end, not

an end unto itself. The net result of this situation is what we would

like to introduce as Buddhist pluralism, a pluralism that we can see

whether we examine Buddhism as a religion, as a philosophy, or as a

culture.

One area where we can see Buddhist pluralism is in the very idea of

the Buddhahood. According to Buddhism there had been a number of Buddhas

in the remote past and there will be a number of Buddhas in the distant

future. The idea behind this is that Buddhahood is not the monopoly of

one individual, but is accessible to all. What is more, the idea of a

number of Buddhas ensures continuity of the opportunities for

emancipation for all living beings at all times. Buddhism recognizes the

immensity of time and the vastness of space and the existence of an

countless number of world-systems. Considered in this cosmic context, to

speak of one Buddha for all time and space is, to say the least,

extremely parochial.

Another area where we can see Buddhist pluralism is in the Buddhist

canonical literature (Tripitaka). If a Buddhist were asked, where do we

get the teachings of the Buddha, he would say it is in the Buddhist

Canon (Tripitaka). Since there are four Buddhist Canons, one in Pali,

one in Chinese, and one in Tibetan, and one in Mongolian, he will have

to specify to which Buddhist Canon he is referring. If he were to say,

for example, it is the Pali Canon, again the reply is not specific

enough because the Pali Canon has many volumes containing the teachings

of the Buddha.

If he is asked to specify one particular volume or book in the Pali

Canon which contains all Buddhist teachings in a summary form he will

fail to identify such a volume or book. Buddhism could be the only

religion with no single canonical work which contains all what the

Buddha taught. Another aspect of Buddhist pluralism we can also see in

the Sangha, the fraternity of monks and nuns. The Sangha, as we all

know, is the Buddhist monastic organization. It could perhaps be the

oldest social organization in the world, having the oldest constitution.

If the Buddhist monastic organization exhibits many elements of

pluralism the reason for this is that it was not intended to be a

pyramid-like organization, a hierarchical organization, where at the top

you find a supreme head. It is not centralized. Its principle of

organization is not perpendicular and vertical, but horizontal and

linear. This allows for diversity within the Sangha organization as we

find it in Japan, China, Tibet, Mongolia, Sri Lanka and other Theravada

countries.

The best example of what we call Buddhist pluralism we can see in

Buddhist culture. What we want to stress here is that when Buddhism was

introduced to a particular country it did not level down that country's

cultural diversity in order to develop some kind of mono-culture. The

various Buddhist countries in the continent of Asia bear evidence to

this. The Buddhist culture in Japan, for example, is different from the

Buddhist culture in Thailand, and both from that of Sri Lanka.

What we need to remember here is that Buddhism is not a culture-bound

religion. Like a bird that leaves one cage and flies to another,

Buddhism can go from one country to another leaving behind its cultural

baggage.

If Buddhism did not level down cultural diversity, the main reason

for this is that Buddhism's social philosophy does not unnecessarily

interfere with the personal lives of its followers. We never hear of a

Buddhist Food, a Buddhist Medicine, a Buddhist Dress, or a Buddhist

Marriage, or a Buddhist way of disposing the dead. Why? Because these

are things that change from time to time and from country to country.

Therefore Buddhism does not superimpose on the individual a rigid and

totalitarian social philosophy which is valid for all time. In

concluding this speech we would like to draw your attention to another

important aspect of Buddhist thinking. It is that as a religion Buddhism

does not say that what is good and noble is confined to the words of the

Buddha. In this connection a Mahayana Buddhist book says: "What is said

by the Buddha is well-said. What is well-said is said by the Buddha."

The first sentence is clear. What the second sentence means is that if

there is anything well-said in any other religion, philosophy, or

ideology, that too is said by the Buddha, in the sense that Buddhism

endorses all that is good and noble from wherever it comes.

In the shape of a circle

Venerable Ajahn Chah

Translated from the Thai Thanissaro Bhikkhu

Continued from December 8

The Buddha wanted us to see sights, hear sounds, smell aromas, taste

flavors, or touch tactile sensations: hot, cold, hard, soft. He wanted

us to be acquainted with everything. He didn't want us to run away and

hide. He wanted us to look and, when we've looked, to understand: "Oh.

That's the way these things are." He told us to give rise to

discernment.

|

|

Whoever

sees the Dhamma sees the Buddha |

How do we give rise to discernment? The Buddha said that it's not

hard - if we keep at it. When distractions arise: "Oh. It's not for

sure. It's inconstant." When the mind is still, don't say, "Oh. It's

really nice and still." That, too, isn't for sure. If you don't believe

me, give it a try.

Suppose that you like a certain kind of food and you say, "Boy, do I

really like this food!" Try eating it every day. How many months could

you keep it up? It won't be too long before you say, "Enough. I'm sick

and tired of this." Understand? "I'm really sick and tired of this."

You're sick and tired of what you liked.

We depend on change in order to live, so just acquaint yourself with

the fact that it's all inconstant. Pleasure isn't for sure; pain isn't

for sure; happiness isn't for sure; stillness isn't for sure,

distraction isn't for sure. Whatever, it all isn't for sure. Whatever

arises, you should tell it: "Don't try to fool me. You're not for sure."

That way everything loses its value. If you can think in that way, it's

really good. The things you don't like are all not for sure. Everything

that comes along isn't for sure. It's as if they were trying to sell you

things, but everything has the same price: It's not for sure - not for

sure in any way at all. In other words, it's inconstant. It keeps moving

back and forth.

To put it simply, that's the Buddha. Inconstancy means that nothing's

for sure. That's the truth. Why don't we see the truth? Because we

haven't looked to see it clearly. "Whoever sees the Dhamma sees the

Buddha." If you see the inconstancy of each and every thing, you give

rise to nibbida: disenchantment. "That's all this is: no big deal.

That's all that is: no big deal." The concentration in the mind is - no

big deal.

When you can do that, it's no longer hard to contemplate. Whatever

the preoccupation, you can say in your mind, "No big deal," and it stops

right there. Everything becomes empty and in vain: everything that's

unsteady, inconstant. It moves around and changes. It's inconstant,

stressful, and not-self. It's not for sure.

It's like a piece of iron that's been heated until it's red and

glowing: Does it have any spot where it's cool? Try touching it. If you

touch it on top, it's hot. If you touch it underneath, it's hot. If you

touch it on the sides, it's hot. Why is it hot? Because the whole thing

is a piece of red-hot iron. Where could it have a cool spot? That's the

way it is. When that's the way it is, we don't have to go touching it.

We know it's hot. If you think that "This is good; I really like it,"

don't give it your seal of guarantee. It's a red-hot piece of iron.

Wherever you touch it, wherever you hold onto it, it'll immediately burn

you in every way.

So keep on contemplating. Whether you're standing or walking or

whatever - even when you're on the toilet or on your almsround: When you

eat, don't make it a big deal. When the food comes out the other end,

don't make it a big deal. Whatever it is, it's inconstant. It's not for

sure. It's not truthful in any way. It's like touching a red-hot piece

of iron. You don't know where you can touch it because it's hot all

over. So you just stop touching it. "This is inconstant. That's

inconstant." Nothing at all is for sure.

Even our thoughts are inconstant. Why are they inconstant? They're

not-self. They're not ours. They have to be the way they are. They're

unstable and inconstant. Boil everything down to that. Whatever you like

isn't for sure. No matter how much you like it, it isn't for sure.

Whatever the preoccupation, no matter how much you like it, you have to

tell yourself, "This isn't for sure. This is unstable and inconstant."

And keep on watching....

Like this glass: It's really pretty. You want to put it away so that

it doesn't break. But it's not for sure. One day you put it right next

to yourself and then, when you reach for something, you hit it by

mistake. It falls to the floor and breaks. It's not for sure. If it

doesn't break today, it'll break tomorrow. If it doesn't break tomorrow,

it'll break the next day - for it's breakable. We're taught not to place

our trust in things like this, because they're inconstant.

Things that are inconstant: The Buddha taught that they're the truth.

Think about it. If you see that there's no truth to things, that's the

truth. That's constant. For sure. When there's birth, there has to be

aging, illness, and death. That's something constant and for sure.

What's constant comes from things that aren't constant. We say that

things are inconstant and not for sure - and that turns everything

around: That's what's constant and for sure. It doesn't change. How is

it constant? It's constant in that that's the way things keep on being.

Even if you try to get in the way, you don't have an effect. Things just

keep on being that way. They arise and then they disband, disband and

then arise. That's the way it is with inconstancy. That's how it becomes

the truth. The Buddha and his noble disciples awakened because of

inconstant things. When you see inconstancy, the result is nibbida:

disenchantment. Disenchantment isn't disgust, you know. If you feel

disgust, that's wrong, the wrong kind of disenchantment. Disenchantment

isn't like our normal disgust. For example, if you live with your wife

and children to the point where you get sick and tired of them, that's

not disenchantment. It's actually a big defilement; it squeezes your

heart. If you run away from things like that, it's being sick and tired

because of defilement. That's not nibbida. It's actually a heavy

defilement, but we think it's disenchantment.

Suppose that you're kind to people. Whatever you have, you want to

give to them. You sympathize with them, you see that they're pretty and

lovely and good to you. Your defilements are now coming around from the

other side. Watch out! That's not kindness through the Dhamma; it's

selfish kindness. You want something out of them, which is why you're

kind to them.

It's the same with disenchantment. "I'm sick and tired of this. I'm

not going to stay any longer. I'm fed up." That's not right at all. It's

a big defilement. It's disenchantment only in name. The Buddha's

disenchantment is something else: leaving things alone, putting them

down. You don't kill them, you don't beat them, you don't punish them,

you're not nice to them. You just put them down. Everything. The same

with everything. That's how it has to be. Only then can you say that

your mind has let go, that it's empty: empty of clinging, empty of

attachment.

Emptiness doesnít mean nobody exists. Or like this glass: Itís not

the case that it has to not exist for us to say that itís empty. This

thermos exists; people exist; everything exists, but those who know feel

in their hearts that these things are truths, theyíre not for sure, they

simply follow their conditions: Theyíre dhammas that arise and disband,

thatís all.

Take this thermos: If we like it, it doesnít react or say anything.

The liking is all on our side. Even if we hate it and throw it into the

woods, it still doesnít react. It doesnít respond to us. Why? Because

itís just the way it is. We like it or dislike it because of our own

attachment. We see that itís good or no good. The view that itís good

squeezes our heart. The view that itís no good squeezes our heart. Both

are defilements.

So you donít have to run away from things like this. Just understand

this principle and keep contemplating. Thatís all there is to it. The

mind will see that these things are no big deal. Theyíre just the way

they are. If we hate them, they donít respond. If we like them, they

donít respond. Weíre simply crazy of our own accord. Nothing disturbs

us, but we get all worked up. Try to see everything in this way.

Itís the same with the body; itís the same with the mind; itís the

same with the moods and preoccupations that make contact: See them as

inconstant, stressful, and not-self. Theyíre just the way they are. We

suffer because we donít want them to be that way. We want to get things

that we simply canít get.

Is there something you want?

ďI guess itís like when I want concentration. I want the mind to be

quiet.Ē

Okay, itís true that you want that. But whatís the cause that keeps

your mind from being quiet? The Buddha says that all things arise from

causes, but we want just the results. We eat watermelons but weíve never

planted any watermelons. We donít know where they come from. We see when

theyíre sliced open and theyíre nice and red: ďMmm. Looks sweet.Ē We try

eating them, and they taste good and sweet, but thatís all we know. Why

watermelons are the way they are, we have no idea.

Thatís because we arenít all-around. All-around in what way? Itís

like watering vegetables. Wherever we forget to water doesnít grow.

Wherever we forget to give fertilizer doesnít grow. Contemplate this

principle and youíll give rise to discernment.

When youíve finished with things outside, you look at your own mind.

Look at the affairs of your body and mind. Now that weíre born, why do

we suffer? We suffer from the same old things, but we havenít thought

them through. We donít know them thoroughly. We suffer but we donít

really see suffering.

When we live at home, we suffer from our wife and children, but no

matter how much we suffer, we donít really see suffering - so we keep on

suffering.

To be Continued

Everlasting service to the Sangha

C M Kalubowila

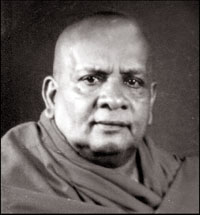

The most venerable Rajakeeya Panditha Bopitiye Wansananda Thera, the

present Anunayake of Sri Lanka Ramangna clan commemorates his 77 birth

anniversary.

|

|

The most venerable, Rajakeeya Panditha,

Bopitiye Wansananda Anunayake Thera of Sri Lanka Ramangna

Maha Nikaya |

He was born in 1934 in a remote village called, Paraigama which

belongs to Pas Yodun Koralaye in the district of Kalutara.

His parents were Iddagoda Hewage Thomas Appuhami and Welipenna

Vithanage Alice Nona. Iddagoda Hewage Dharmasena was their eldest son

who entered in to the monastic life, on 3rd of May in the year 1946 by

the name of Bopitiye Wansananda.

After being ordained as a monk he received his primary education at

Siri Vijaya Dharama Pirivena in Induruwa. He studied there as a student

of the most venerable Induruwe Uththarananda and Pandit Matara

Dhammawansa Theras.

He ordained his higher ordinance in 1954 and at the same year he

entered into the Vidyalankara university for his higher education. In

university he acquired the 'Stubbs governor award' for archaeology

donated to the past student.

After passing out in 1958, he joined as a teacher of Dharmodaya

Pirivena in Wellawaththa and served there more then 10 years.

Later he moved to Payagala Dharma Gupta Pirivena and assumed the

principal post. Subsequently he has become the chief incumbent of Athula

Maha Viharaya also.

During the past period he has possessed so many higher ranks in the

Ramangna Maha Nikaya before access to the present Anu Nayake post.

It's very appreciable that this pious and erudite monk serves to the

public without any discrimination of caste or creed in our multi-ethnic

area, according to the Buddhist-vision. To be engaged on his invaluable

religious and social works further, may the Triple Gems Bless, on his

77th birthday commemoration. Long live our Anunayake Thera to serve the

nation and the country. |