|

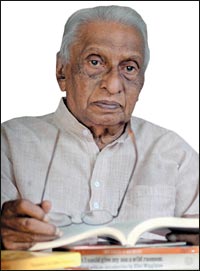

Gunadasa Amarasekara:

Musings on an incomplete journey

Sachitra Mahendra

|

Gunadasa Amarasekara.

Pictures by Saman Sri Wedage

|

He is profoundly at home with both folk and classical poetry. He

would recite verses in Selalihini Sandesa and Guttila by heart. Yet his

profession is poles apart, being a dental surgeon.

Dr. Gunadasa Amarasekara marks his position in Sinhala literature

more as a poet, though he started off writing short stories and went

ahead with the novel. He accelerated the Sinhala poetry syringing his

influence from the folk tradition.

Although he belongs to a bilingual generation Amarasekara has not

written a single creative work in English.

“You should write to your immediate audience. So to say, you have to

write in the indigenous language.”

English authors

What is wrong with writing in English, then? Amarasekara questions

about the audience of Sri Lankan English authors. Writing in English

indicates a certain psychological condition: inferiority complex. Some

local English novelists do not seem to have read classical literature at

all, Amarasekara opines.

“If we are to write a creative piece in English, then it should have

a universal appeal, shouldn’t it? I don’t think our Sri Lankan English

literature has a universal appeal. In fact I have never seen our English

publications in European markets.”

If Sinhala literature stagnates, Amarasekara goes on to say, Sri

Lankan English literature should be a worse case then. Most of the

Sinhalese writers are at least familiar with the local pulse beat.

English writers have to take up the challenge of making the reader

familiar with the local environment. It will nevertheless sound foreign

as well as alienated.

Language shift

Our modern generation is full of monolinguals, owing to the official

language shift in 1956. This has more disadvantages than advantages. The

Sinhala writer’s literary scope has become confined.

“Great writers like Martin Wickramasinghe and Ediriweera

Sarathchandra were bilinguals. They read quite a lot of English works,

and they had an unlimited access to a wide literature.”

Wide literature! Since English became the international language,

nearly every masterpiece has been translated into English. You enjoy all

world renowned masterpieces, only if you have a good command in English.

But that doesn’t mean you can write in English with equal nuances.

“Remember all great artistes such as Boris Pasternak wrote in their

indigenous languages. They talked to the hearts of the immediate

audience. You cannot arouse same pathos with a second language.”

Fluent English

Professor Ediriweera Sarachchandra was fluent in many languages

including English. But he could not get the same imagination power in

his works translated into English by himself. Reggie Siriwardana notes

Sarachchandra’s creative English is so weak.

“I may have my personal conflicts with Sarachchandra. But he is a

genius in his Sinhala creative works, no doubt. Sarachchandra was well

received in the local audience, because he wrote in the common man’s

language.”

We require English to get influence, not to imitate.

Classical literature

“I fervently believe in our ancient Sinhala literature. But our

horizons widen, when we study beyond our own literature. We start

comparing the literatures.

We become familiar with the classical literature, ultimately.

Danger of being a monolingual is to entertain half baked western

concepts. Many mug up translations, misunderstand and start imitating

western concepts such as post modernism.

His village Yatalamatta, in which he was born in 1929, is present in

many of his creative works. He always touches the fondness of coming

back to the roots. Sometimes it is sensitive.

Sometimes it is harsh. All his works, be it a novel, short story,

poetry or literary criticism, reflect that more or less.

He headed the new Peradeniya school of poets in the 1950s, when he

completely turned down the idea of foreign influence.

He had clashes with Ediriweera Sarathchandra and Siri Gunasinghe who

dwelled on the Western influence.

“I had the access to English literature. But our Sinhala folk poetry

amused and amazed me a lot. I was sort of drowned in their poetic

spirit.” Amarasekara recollects his memories, softly.

Pseudo intellectuals

|

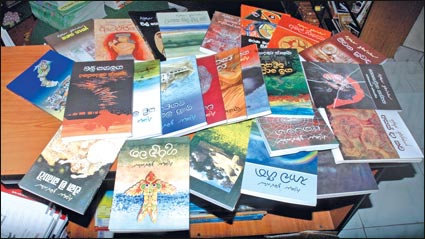

Some of Gunadasa Amarasekara’s books |

He is always tough on the pseudo western educated intellectuals, who

look down on our cultures. All his creative works, in that sense,

reflect a sort of disillusionment.

“I felt this disillusionment for the first time, when I left for

England. I saw how our people try to get along with the Whites, and I

felt how futile it was. The Whites seemed to be happy the idea that we

are a poor nation.”

The Whites must have laughed at secrecy seeing us trying get along

with their customs; we being their one-time colonies, after all.

This made Amarasekara go back to roots, in a stern sense.

His publisher, Gevindu Kumaratunga, takes every effort to bring out

all the publications in an eye-catching form. Gevindu has the rare luck

of being a grandson of legendary Sinhala writer Kumaratunga Munidasa.

“Gevindu is a perfectionist. He wants everything perfectly done. I

think that’s why I find proof errors very rarely.”

Gunadasa

Amarasekara is a rare species who can write beautiful classical Sinhala

generating sensitive imagination. Gunadasa

Amarasekara is a rare species who can write beautiful classical Sinhala

generating sensitive imagination.

Yet the very same man is harsh about the way the modern novel is

headed.

Ancient classics

“Our novel deteriorates so fast. This is because our novelists

neither read ancient classics nor western classics. They just touch an

elephant blindfolded, and come out with good for nothing works.

I am looking forward to seeing an era when our creative writers

manipulate the ancient classics and be influenced by the western

classics.”

When that dream will come true, we can only wonder.

An excerpt from short story Disonchinahami

How pleased his professor would be to read this report on

Disonchinahamy; Kumar could predict that he would write back immediately

asking for all the details of the case.

How rearely did one encounter the kind of tumour found on

Disonchinahamy; Kumar remembered his professor mentioning that in all of

medical literature there were only three accurate reports of this

particular tumour which had long been a matter of serious controversy.

If so, would not this be the fourth such accurate report? Yet, in

preparing the report, who should he approach the matter? This was the

big question, the major problem facing him from the moment he sat down

to write his report.

Should he consider it a ‘giant cell granuloma’ a giant cell tumour or

a giant cell sarcoma? Was this a situation that contradicted the theory

that giant cell tumours only occurred in long bones and not in jaw

bones? It was not necessary to come to nay final decision on this.

Nobody expected that.

But how good it would be if one could treat it in the report as a

giant cell tumour, which all the available evidence seemed to indicate

it was.

Translated by Ranjini Obeysekere

... forte in poetry

In his ‘Enabling Traditions’ Professor Wimal Dissanayaka gives a

strap line to his essay on Gunadasa Amarasekara: Poetry, Tradition and

Social Truth.

That sums up Gunadasa Amarasekara’s forte. He entered the poetry

stream with his collection Bhava Geetha in 1955. With all spirits of a

youth, he attempted to remodel the poetry.

He believed the poetry should touch the modern issues.

Poets such as Ananda Rajakaruna, Sri Chandraratne Manawasinghe and G.

H. Perera used the poetry to address modern issues too, but they were

often confined to the traditional metre. Amarasekara got on to seek a

modified metre.

He was influenced by Kumaratunga Munidasa’s Piya Samara for the first

time. Uyanaka Hinda Liyu Kavi bears testimony for Amarasekara’s

influence.

Amarasekara was always fond of the sound quality of the poetry. He

did not believe much in free verse, which doesn’t give out the sound

beauty.

He was largely influenced by works such as Sihaba Asna and Dalada

Siritha in arousing sound in the poetry.

If his Amal Biso touches the folk feature of the poetry, a later

collection Gurulu Vatha denotes more emphasis on classical myth. With

Amal Biso Amarasekara gives the lie to the opinion that the folk poetry

is restricted in its pathos.

Amarasekara always found solace in poetry. It was nowhere but the

language of heart for him. In fiction Amarasekara doesn’t reach the

aesthetic climax which he could handle with such mastery in poetry.

... in fiction

His first short story Soma won much accolades in 1952. It was

translated into English in the US later on. He takes a revolutionary

step in 1955 with Karumakkarayo. This novel reflects a rarely touched

social trait: a woman having relationship of incest with her brothers

and indicatively with father. When he wrote Yali Upannemi, he was put to

censure from many quarters – likes of Ven. Henpitagedara Gnanasiha and

Martin Wickramasinghe – save Ediriweera Sarathchandra who admired and

recommended the work to be introduced into other languages. Amarasekara

followed D. H. Lawrence, Andre Gide and the Japanese erotic style mainly

in authoring Yali Upannemi. He accepted the criticism, hence no reprint

is available since the 60s.

Following this episode, Amarasekara’s novels took a new shape. He

initiated a self-referential middle class journey with eight novels:

1. Gamanaka Mula

2. Gam Dorin Eliyata

3. Inimage Ihalata

4. Vanka Giriyaka

5. Yali Maga Vetha

6. Duru Rataka

Dukata Kiriyaka

7. Gamanaka Meda

8. Ataramanga

(launched recently at the Colombo International Book Fair)

These novels portray Amarasekara’s political philosophy. He foresaw a

youth insurrection early in the 1960s.

Amarasekara was looking forward to seeing a younger generation who

can stand alone without the state support.

But that youth resurrection did not turn out positive as he thought

it would be.

Amarasekara’s literary contributions

Novelist

Karumakkarayo

Yali Upannemi

Depa Noladdo

Gandhabba Apadanaya

Asatya Kathavak

Premaye Satya Kathava

Gamanaka Mula

Gam Doren Eliyata

Ini Mage Ihalata

Vankagiriyaka

Yali Maga Vetha

Duru Rataka Dukata

Kiriyaka

Gamanaka Meda

Short Story writer

Ratu Rosa Mala

Jeevana Suvanda

Ekama Kathava

Ektemen Polovata

Katha Pahak

Gal Pilimaya saha Bol

Pilimaya

Marana Manchakaye

Dutu Sihinaya

Pilima Lovai Piyevi Lovai

Vil Thera Maranaya

Poet

Bhava Geetha

Uyanaka Hinda Liyoo

Kavi

Amal Biso

Gurulu Vatha

Avarjana

Asak Da Kava

Polemicist

Abuddassa Yugayak

Anagarika Dharmapala

Marxvadida?

Ganaduru Mediyama

Dakinemi Arunalu

Arunaluseren

Arunodayata

Jathika Chinthanayai

Jathika Arthikayai

Sinhala Kavya

Sampradaya

Samaja Deshapalana

Vichara I

Samaja Deshapalana

Vichara II

Nosevuna Kedapatha:

Navakathave

Parihaniya |