Terror in Mumbai - a legal perspective

Ruwantissa ABEYRATNE

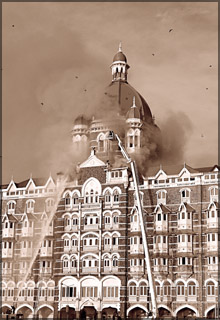

On Wednesday 26 November 2008 groups of gunmen carried out brazen

coordinated attacks on at least 10 sites in Mumbai, killing at least 125

people and wounding more than 300.

Through the years there have been numerous acts of criminality

perpetrated against foreigners, the most common of which have been

violence against civil aviation and attacks aimed at foreign embassies.

There are various offences that can be perpetrated by private

individuals or groups of individuals against civil aviation, the

earliest common species of which was hijacking of aircraft.

Hijacking

Hijacking, in the late 1960s started an irreversible trend which was

dramatised by such incidents as the skyjacking by Shiite terrorists of

the TWA flight 847 in June 1985. The skyjacking of Egypt Air flight 648

in November the same year and the skyjacking of a Kuwait Airways Airbus

in 1984 are other early examples of this offence. Aviation sabotage,

where explosions on the ground or in mid air destroy whole aircraft,

their passengers and crew, is also a threat coming through the past

decades.

The Air India flight 182 over the Irish Sea in June 1985, PAN AM

flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland in 1988, and the UTA explosion over

Niger in 1989 are examples. Missile attacks, where aircraft are

destroyed by surface to air missiles (SAM) have also occurred as early

as in the seventies. The destruction of the two Viscount aircraft of Air

Rhodesia in late 1978/ early 1979 are examples of this offence. A

re-emerging threat, namely armed attacks at airports, shows early

occurrence in instances where terrorists opened fire in congested areas

in the airport terminals. Examples of this type of terrorism are: The

June 1972 attack by the Seikigunha (Japanese Red Army) at Ben Gurion

Airport, Tel Aviv; The August 1973 attack by Arab gunmen on Athens

Airport; and the 1985 attacks on Rome and Vienna Airports.

The suicide bombing of the United States Embassy in Beirut in April

1983 that killed over 60 people, mostly embassy staff members and U.S.

marines and sailors was one of the deadliest attacks on foreigners ever

carried out. In March 1992 the Israeli Embassy in Buenos Aires was

bombed as a consequence of which 29 people lost their lives and hundreds

were wounded including embassy staff and passers-by, Argentinians and

Israelis. Hundreds of people were killed in simultaneous car bomb

explosions at United States Embassies in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and

Nairobi, Kenya.

Jurists and lawyers have grappled with and evolved principles on the

responsibility of a State for private acts of criminality against

foreigners on their soil. The fundamental principle that has emerged in

this sustained evolution is that a State cannot be expected to

anticipate every act of terrorism and therefore does not carry absolute

liability. However, at international law, there are concrete legal

principles that evaluate the responsibility of a State for private acts

committed against foreigners.

The fundamental issue in the context of State responsibility for the

purposes of this article is to consider whether a State should be

considered responsible for its own failure or non-feasance to prevent a

private act of terrorism against civilians, both foreigners and locals

alike.

Theory of Complicity

At the core of the principal-agent dilemma is the theory of

complicity, which attributes liability to a State that was complicit in

a private act. Hugo Grotius (1583-1645), founder of the modern natural

law theory, first formulated this theory based on State responsibility

that was not absolute. Grotius’ theory was that although a State did not

have absolute responsibility for a private offence, it could be

considered complicit through the notion of patienta or receptus. While

the concept of patienta refers to a State’s inability to prevent a

wrongdoing, receptus pertains to the refusal to punish the offender.

A different view was put forward in an instance of adjudication

involving a seminal instance where the Theory of Complicity and the

responsibility of states for private acts of violence was tested in the

Jane case of 1925. The case involved the Mexico-United States General

Claims Commission which considered the claim of the United States on

behalf of the family of a United States national who was killed in a

Mexican mining company where the deceased was working. The United States

argued that the Mexican authorities had failed to exercise due care and

diligence in apprehending and prosecuting the offender.

The decision handed down by the Commission distinguished between

complicity and the responsibility to punish and the Commission was of

the view that Mexico could not be considered an accomplice in this case.

Condonation Theory

The emergence of the Condonation Theory was almost concurrent with

the Jane case decided in 1925 which emerged through the opinions of

scholars who belonged to a school of thought that believed that States

became responsible for private acts of violence not through complicity

as such but more so because their refusal or failure to bring offenders

to justice was tantamount to ratification of the acts in question or

their condonation.

The theory was based on the fact that it is not illogical or

arbitrary to suggest that a State must be held liable for its failure to

take appropriate steps to punish persons who cause injury or harm to

others for the reason that such States can be considered guilty of

condoning the criminal acts and therefore become responsible for them.

The responsibility of governments in acting against offences

committed by private individuals may sometimes involve condonation or

ineptitude in taking effective action against terrorist acts, in

particular with regard to the financing of terrorist acts. The United

Nations General Assembly, on 9 December 1999, adopted the International

Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism, aimed at

enhancing international co-operation among States in devising and

adopting effective measures for the prevention of the financing of

terrorism, as well as for its suppression through the prosecution and

punishment of its perpetrators.

The Convention, in its Article 2 recognises that any person who by

any means directly or indirectly, unlawfully or wilfully, provides or

collects funds with the intention that they should be used or in the

knowledge that they are to be used, in full or in part, in order to

carry out any act which constitutes an offence under certain named

treaties, commits an offence.

|

Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh meets an injured person in

hospital as Congress party president Sonia Gandhi looks on. AP |

One of the treaties cited by the Convention is the International

Convention for the Suppression of Terrorist Bombings, adopted by the

General Assembly of the United Nations on 15 December, 1997.

The United Nations has given effect to this principle with Resolution

2625 (XXV) of 24 October 1970 when it proclaimed that every State has

the duty to refrain from organizing or encouraging the organization of

irregular forces or armed bands, including mercenaries, for incursion

into the territory of another State. Every State has the duty to refrain

from organizing, instigating, assisting or participating in acts of

civil strife or terrorist acts in another State or acquiescing in

organized activities within its territory directed towards the

commission of such acts, when the acts referred to in the present

paragraph involve a threat or use of force.

Encouraging

Here, the words encouraging and acquiescing in organized activities

within its territory directed towards the commission of such acts have a

direct bearing on the concept of condonation and would call for a

discussion about how States could overtly or covertly encourage the

commission of such acts. Steven Metz, in his article State Support for

Terrorism, Defeating Terrorism, Strategic Issue Analysis identifies

three categories of such support: Category I support entails protection,

logistics, training, intelligence, or equipment provided terrorists as a

part of national policy or strategy; Category II support is not backing

terrorism as an element of national policy but is the toleration of it;

Category III support provides some terrorists a hospitable environment,

growing from the presence of legal protections on privacy and freedom of

movement, limits on internal surveillance and security organizations,

well-developed infrastructure, and emigrant communities.

The International Law Commission in its Draft Code of Crimes Against

the Peace and Security of Mankind, International Law Commission Report

(1996, Chapter II Article 2) has established that a crime against the

peace and security of mankind entails individual responsibility, and is

a crime of aggression.

Role of Knowledge

Another method of determining State responsibility lies in the

determination whether a State had actual or presumed knowledge of acts

of its instrumentalities, agents or private parties which could have

alerted the State to take preventive action. International

responsibility of a State cannot be denied merely on the strength of the

claim of that State to sovereignty.

Apart from the direct attribution of responsibility to a State,

particularly in instances where a State might be guilty of a breach of

treaty provisions, or violate the territorial sovereignty of another

State, there are instances where an act could be imputed to a State.

Imputability or attribution depends upon the link that exists between

the State and the legal person or persons actually responsible for the

act in question.

The sense of international responsibility that the United Nations

ascribed to itself had reached a heady stage at this point, where the

role of international law in international human conduct was perceived

to be primary and above the authority of States. In its Report to the

General Assembly, the International Law Commission recommended a draft

provision which required that every State has the duty to conduct its

relations with other States in accordance with international law and

with the principle that the sovereignty of each State is subject to the

supremacy of international law.

This principle, which forms a cornerstone of international conduct by

States, provides the basis for strengthening international comity and

regulating the conduct of States both internally - within their

territories - and externally, towards other States. States are

effectively precluded by this principle of pursuing their own interests

untrammelled and with disregard to principles established by

international law.

The above discussion leads one to conclude that the responsibility of

a State for private acts of individuals is determined by the quantum of

proof available that could establish intent or negligence of the State,

which in turn would establish complicity or condonation on the part of

the State concerned. One way to determine complicity or condonation is

to establish the extent to which the State adhered to the obligation

imposed upon it by international law and whether it breached its duty to

others.

In order to exculpate itself, the State concerned will have to

demonstrate that either it did not tolerate the offence or that it

ensured the punishment of the offender. Professor Ian Brownlie in his

book System of the Law of Nations: State Responsibility brings forth the

view that proof of such breach would lie in the causal connection

between the private offender and the State. In this context, the act or

omission on the part of a State is a critical determinant particularly

if there is no specific intent. Generally, it is not the intent of the

offender that is the determinant but the failure of a State to perform

its legal duty in either preventing the offence (if such was within the

purview of the State) or in taking necessary action with regard to

punitive action or redress.

Finally, there are a few principles that have to be taken into

account when determining State responsibility for private acts of

individuals that harm foreigners in their territories. Firstly, there

has to be either intent on the part of the State towards complicit or

negligence reflected by act or omission. Secondly, where condonation is

concerned, there has to be evidence of inaction on the part of the State

in prosecuting the offender. Thirdly, since the State as an abstract

entity cannot perform an act in itself, the imputability or attribution

of State responsibility for acts of its agents has to be established

through a causal nexus that points the finger at the State as being

responsible. For example, The International Law Commission, in Article 4

of its Articles of State Responsibility states that the conduct of any

State organ which exercises judicial, legislative or executive functions

could be considered an act of State and as such the acts of such organ

or instrumentality can be construed as being imputable to the State.

This principle was endorsed in 1999 by the International Court of

Justice which said that according to well established principles of

international law, the conduct of any organ of a State must be regarded

as an act of State.

The law of State responsibility for private acts of individuals has

evolved through the years, from being a straightforward determination of

liability of the State and its agents to a rapidly widening gap between

the State and non State parties. In today’s world private entities and

persons could wield power similar to that of a State, bringing to bear

the compelling significance and modern relevance of the agency nexus

between the State and such parties. This must indeed make States more

aware of their own susceptibility.

(The writer is

Coordinator, Air Transport Programmes International Civil Aviation

Organization, Montreal, Canada.) |