The beginning of the Cuban revolution

Marta ROJAS

The assault on the Moncada Garrison in Santiago de Cuba on July

26, 1953, by a group led by Fidel Castro was an event that the world was

unaware of.

Cuban newspapers - with just one exception - noted that the young

Cuban lawyer Fidel Castro together with a contingent of young men, had

assaulted the country’s second military fortress, with the aim of

reverting the situation of Cuba; in other words, to restore the crushed

Constitution of the Republic by overthrowing General Fulgencio Batista

who, barely one year earlier - on March 10, 1952 - had mounted a coup

d’‚tat to seize power from President Carlos Prio Socaro s,

democratically elected at the polls.

Cunning coup

His presidency was due to end normally that same year. That cunning

coup was known as the “crack of dawn.” Its executor and those who

followed him did not have popular support. From 1933, Batista’s history

was symbolised by dictatorial ambitions and crime.

|

Raul Castro |

|

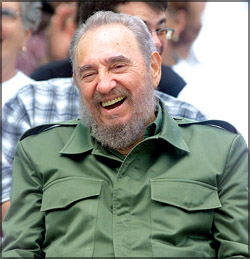

Fidel Castro |

From that time, he was recalled by his contemporaries and the people

as the military chief who ordered the killing of revolutionaries Antonio

Guiteras and Venezuelan Carlos Aponte.

Guiteras formed part of the revolutionary government that took power

after the fall of the dictator Gerardo Machado and, in the so-called 100

Days’ Government, acted as government minister and drew up the most

advanced legislation of the 20th century to that point, including the

nationalization of foreign companies established in Cuba, even though

neither he nor the other members of that government were communists.

After these brief historical antecedents, it is obligatory to go back

to that event unknown to the world, the Moncada assault. Only one

reporter from a US news agency sent a cable from his office on the armed

attack, but he never found out which newspapers published it apart from

the Havana Post, an English-language newspaper in Havana.

Only the dailies in Santiago de Cuba - in what used to be Oriente

province - and those of Havana, as well as national radio covered the

news, and the “In Cuba” section of Bohemia magazine printed photographs.

Other newspapers in the country reproduced the Bohemia photos. And that

was it.

That same day the Batista dictatorship, which was called the “de

facto” government, decided to implement the harshest press censorship,

given that it was not confined to an order but appointed censors in

every newspaper and other media.

General elections

The only version of the event was the military information released

by the Columbia Camp, headquarters of the Army General Staff that had

executed the military coup, headed by the then senator Batista, who had

just returned from exile in Miami to participate in the general

elections on June 1, 1952 in which he aspired to be formally appointed

as such.

Thus, the world was unaware that, on just one day, July 26 itself - a

Sunday - 46 young combatants who were captured were extra-judicially

tortured and finally murdered, and in the following days that figure

rose to more than 60, although the military reports said that they had

died in combat with the army. On July 26 only six revolutionary

combatants fell in fighting at Post 3 of the Santiago de Cuba garrison.

The organisation led by the young lawyer Fidel Castro came to be

popularly known as the Centenary Generation, given that it emerged -

after months of underground organisation - precisely in 1953, with

celebrations for the centenary of the birth of Jos‚ Marti, leader of the

Cuban independence struggle against Spanish colonialism and the national

hero.

Marti’s thinking on full freedom and sovereignty, his revolutionary

ethics and social ideas, among other fundamental values, was the

doctrine assumed by that young contingent, almost all of them members of

the youth wing of the Cuban Orthodoxy People’s Party, the majority

political group in the country, and which would certainly have won the

presidency of the Republic of Batista had not interrupted the

constitutional process, and the elections scheduled for June 1 had taken

place.

So that was why, during the trial of the Moncada assailants on

September 21, 1953, when the prosecution judge asked Fidel who had

masterminded the action, he emphatically replied that nobody should be

concerned about being accused in that context, because the sole author

of the Moncada assault was Jos‚ Marti. It was already known via the

Movement’s programme and Fidel’s own words that they were the bearers of

“the doctrines of the maestro.”

Dictatorship

That unknown event was a tactical setback, given that its prime

objective was not achieved. It was to take the garrison by surprise and

call on the people to fight against the dictatorship and restore the

1940 Constitution abolished by the coup d’‚tat, a model in vogue in

Latin America up until the days of Pinochet in Chile, always backed - in

all cases - by the government in power in the United States, forgetting

its fanatical defense of democracy and multi-party elections.

The tactical setback began to turn into a strategic victory from

September 21 when the leader of the Revolutionary Movement and the

assault on Moncada - Dr. Fidel Castro - appeared for the first time

before the court in the Santiago de Cuba Palace of Justice, as the

accused and defense lawyer for the Moncada assault.

His statements and the interrogation process - as a lawyer - were so

devastating to the fallacious versions circulated since July 26 by

Batista and his military acolytes that, in 48 hours, the trial changed

course and Fidel, the accused, became the accuser.

His arguments were so powerful that they crushed all the maneuverings

of the court and the “de facto” government. His reasoning was so strong

that a doctor from the Boniato (in Santiago) prison was summoned to

certify that Dr. Castro was supposedly suffering from an illness, to

prevent his return to the trial proceedings against him, the other

survivors of the assault and a group of opposition politicians who had

nothing to do with the Movement but whom the regime involved in the

event.

There were many people listening, adding up more than 100 members of

the armed forces, relatives of the prisoners, 25 lawyers, court

employees and some 20 journalists, even though their newspapers, being

censored, were unable to publish anything.

The dictatorship certainly feared that, starting with Santiago de

Cuba, the word would go from mouth to mouth and that the people would

get to know the truth. They would discover the number of atrocities

committed by the army under orders from on high that at least 10

assailants had to be killed for every soldier that died in combat.

The trial of the others continued under a protest from Fidel sent to

the court via Melba Hernandez, a lawyer who, with Hayd‚e Santamaria, was

one of the two women who participated in the assault.

They were with the group commanded by Abel Santamaria,

second-in-command of the Movement, localised in the service area of the

Saturnino Lora Civilian Hospital. The young Raul Castro was the leader

of the contingent of the other rearguard, located on the flat roof of

the Palace of Justice.

Journalists

It was not until October 16 that Fidel Castro appeared before the

court again. This took place in a nurses’ study room in the Civilian

Hospital where, as he himself said in his plea, the public consisted of

just six journalists in whose newspapers nothing could be published.

Obviously, the censorship continued in place. It was here that Fidel

gave his own defense plea that is now known everywhere as History Will

Absolve Me, a speech that he himself reproduced in written form during

his imprisonment in the former Model Prison on the Isle of Pines (now

the Isle of Youth).

Next October 16 will be the 55th anniversary of that event, virtually

carried out in isolation, of which the world knew nothing at the time,

but only later, in 1954, when History Will Absolve Me was published and

distributed clandestinely in Cuba and reproduced by revolutionary

friends in New York, and by a small publishing house in the Republic of

Chile. In this last case, the book was on display in a bookstore window.

One of the aspects successfully concealed from the public attending

the Moncada trial was the file of death certificates made by brave

forensic surgeons who removed or autopsied the corpses of the

revolutionary assailants.

In some of them, the doctors noted as evidence of crime, that the

fingers of the dead were stained with the ink used for taking their

fingerprints before they were killed, plus many other details. It was

from their notes that it emerged that the young Movement members who

left the Civilian Hospital alive, including Abel Santamaria, were

wearing hospital gowns or pajamas under khaki pants that showed no sign

of bloodstains.

But, in passing, the solidarity of the people, primarily expressed by

the hospital nurses, was evident. They tried to hide the young

assailants so that they wouldn’t be killed and made them put on hospital

garb to pass them off as patients in different wards. Abel’s pajamas

bore the initials of the Ophthalmology room; perhaps it was for that

reason that during his torture they pulled out or crushed the bandaged

eye.

Nevertheless, the forensic certificates of the soldiers killed in

combat were very clear: orifice of the entry or exit of bullets. All the

certificates in the files of Cause 37 of the Emergency Court are

considered as irrefutable evidence.

As if that were not enough, they include a photo of Jos‚ Luis Tasende,

a revolutionary combatant who was wounded at one of the posts and, as

chief of the cell, wore sergeant stripes.

He was mistaken for an injured soldier (the assailants wore the same

uniforms but with civilian belts, for example, as a different or

distinguishing feature) and was even treated at the Military Hospital.

He had a sutured wound on one leg, was photographed by the Army as a

hero and, when it emerged that he was fighting as an assailant, he was

“killed in combat.” The photo of a living Tasende is categorical

evidence.

None of that was known to the world at that time.

Deep-rooted

However, the actions of July 26, 1953 were to transform the political

map of Cuba and the rest of the Americas and constituted a solid example

of how such a social, deep-rooted revolution was possible.

The example given by that eminent group of Cubans — followed by the

struggle and victory of the amnesty; the Granma expedition and the

battles of the Rebel Army in the Sierra Maestra; the uniting of the

revolutionary groups; the general strike of January 1, 1959 called by

Fidel himself, as commander in chief; and the 55 years of resistance of

a people - is the guarantee of the significance of that day of which the

world knew nothing.

The writer is a Cuban journalist and writer. In the form of a

journalistic novel, her anthological testimony of the events described

in this article can be found in detail in “El juicio del Moncada”

(The Moncada Trial). |