MARVELLING AT MARVELL

‘Anything more than the truth would have seemed too

weak’ :

We have already marvelled at Shakespeare's anticipation some two

hundred years earlier of Coleridge's definition of the imagination's

role in the creative process. We have already marvelled at Shakespeare's anticipation some two

hundred years earlier of Coleridge's definition of the imagination's

role in the creative process.

We might also marvel that with all the creative fecundity of the

intervening years there should have be no other precedents to

Coleridge's insights. However, our re-examination of Marvell's ‘The

Garden’ last week suggests that there has, in fact, been just such a

link.

It is to be found in the climactic sixth verse of the poem which we

analysed in terms of the poem's context, namely the influence of nature.

We noted that Marvell had anticipated Wordsworth's discovery a

century later of nature's revelatory role, as described in ‘Tintern

Abbey'. What we had not realised is that Marvell also seems to have

anticipated the discovery of Wordsworth's contemporary, Coleridge,

regarding the modus operandi of the imagination.

|

|

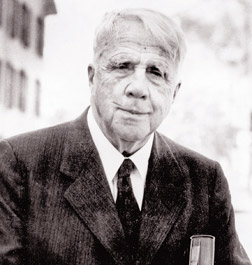

Robert

Frost |

Of course, there is no specific reference to the imagination, as in

the case of Shakespeare's earlier preview, which is why the significance

of the verse may not have been obvious.

Like Shakespeare, however, it effectively describes the role of the

imagination in poetic terms; and like Coleridge it is quite explicit as

to the manner of the imagination's functioning. Nor is it a mere

bridging of the gap that this verse provides. It actually enhances our

understanding of the subject.

For, where Shakespeare describes the results of the imagination at

work, ie. things unseen getting a local habitation and name; and

Coleridge explains what he calls the esemplastic or all-encompassing and

unifying role the imagination plays; what Marvell does - once we

acknowledge this aspect of the significance of the verse - is to show

how the imagination gets the mind of the poet to work on the recreation

of experience.

As such Marvell's is probably the most practical of the three

definitions. But let us look afresh at the verse:

“Mean while the Mind, from pleasure less, Withdraws into its

happiness: The Mind, that Ocean where each kind Does streight its own

resemblance find; Yet it creates, transcending these, Far other Worlds,

and other Seas; Annihilating all that's made To a green Thought in a

green Shade.”

The point to be made is that in this verse Marvell is not only

revealing how the contemplation of Nature leads to an otherwise

unobtainable level of enlightenment, as does Wordsworth.

He is at the same time, perhaps unwittingly, revealing the

imaginative process whereby the poet is able to achieve such

enlightenment. In other words, Marvell is revealing the creative

imagination at work as no other poet has done.

In the first couplet we see what follows the sensory experience

where, in the imaginatively exquisite description of the previous verse,

nature seems to overpower the poet so that ‘insnar'd by Flowers, he

falls on grass.” At this climactic point the mind begins to retreat from

the external world of the senses into an interior world of its own

making.

Here the mind finds a different kind of joy. It has to do with the

mind forming its own its impressions of the external realities to which

it has been exposed. The next couplet, comparing the mind to an ocean,

reflects the prevalent belief that all land species have their

counterparts in the sea. But it is also a virtual figurative version of

the dictionary definition of imagination as “a mental faculty forming

images or concepts of external objects not present to the senses.”

But of course the creative imagination goes far beyond the mere

dictionary definition of its role. And this is what the next couplet

brings out as the transcending of these images and the creation of

further worlds or realms of thought.

And this is precisely the transformational role of the imagination

that Coleridge would go on to explain. As the mind goes on pondering its

experience of reality the imagination so transforms the original

impressions as to facilitate the perception of realities hitherto

unconsidered.

At this point we are at the stage that Keats describes as ‘magic

casements being charmed to open on the foam of perilous seas in faery

lands forlorn.’ Could Keats have had Marvell's ‘far other Seas’ in mind

when he wrote that line?

Finally this recreation of experience results in a fresh insight into

life in which everything seems to fall into place. It is the sort of

epiphanous experience we have come to expect from great literature. The

ultimate meaning of life is simplified into a single thought, a simple

insight. Yet – and herein lies the greatness of a Marvell's wit whereby

seriousness is intensified by levity – that green thought could not have

come without the green shade.

Nor could the green shade of the creative process have come about

without the greenery of the garden, the sensory impressions that gave

rise to the imaginative process in the first instance.

Thus, to quote Eliot this time, it is ‘a condition of complete

simplicity costing not less than everything.’ Yes, the imagination has

brought the totality of the poet's experience and the totality of his

being into activity to arrive at this sublime clarity of perception.

And so, some seventy five years after Shakespeare and some hundred

and twenty five years before Coleridge, we have this wonderful

revelation from Marvell. Without using the word at all, he reveals how

the imagination works to recreate experience and present it as something

rich and strange to the poet and to the reader alike.

He also, in that last line, makes the point that the imagination is

firmly grounded in reality, rather than taking off on ethereal flights

of fancy as Keats’ line might suggest.

And this reminds us of what Wallace Stevens once said: “The

imagination loses vitality as it ceases to adhere to what is real. When

it adheres to the unreal, while its first effect may be extraordinary,

that effect is the maximum effect that it will ever have.” One of the

finest examples of this truth is Robert Frost's poem, ‘Mowing':

“There was never a sound in the wood but one, And that was my long

scythe whispering to the ground.

What was it it whispered? I knew not well myself; Perhaps it was

something about the heat of the sun, Something, perhaps, about the lack

of sound – And that was why it whispered and did not speak.

It was no dream of the gift of idle hours, Or easy gold at the hand

of fay or elf: Anything more than the truth would have seemed too weak

To the earnest love that laid the swale in rows, Not without

feeble-pointed spikes of flowers (Pale orchises), and scared a bright

green snake. The fact is the sweetest dream that labour knows. My long

scythe whispered and left the hay to make.”

In this poem there are no images. It disabuses us of the idea that

could have arisen from the previous three examples that the imagination

must have figurative richness of language, a profusion of metaphors and

similes, to perform its transformational role. Frost simply describes

himself at work in a field of grass with his scythe.

He does not compare the activity with anything else. He avoids any

make-believe about it.

And then comes the great truth or insight from the imaginative grasp

of reality. Anything more than the truth, the actuality of the

experience, would be uncalled-for. The earnest love of labour performed

in close contact with the earth needs no sentimentalising or glorifying.

The fact of such labour provides its own sweet dream.

The imagination, working on the poet after the experience of his

labour, brings him a fresh insight about the significance of work: in

the words of Yeats, that “labour is blossoming and dancing”.

Labour is its own reward when undertaken in the right spirit with an

understanding of its intrinsic dignity. It provides a joy that down-time

can never provide, a sense of fulfilment and peace that comes from the

bodily exertion in connection with the earth that man was made for. That

is Frost's green thought in his green shade.

|