|

The poetry of prose:

‘Fog everywhere’

Last week I suggested that the poetic quality of Henry James’

nouvelle, ‘The Beast in the Jungle’, could only have been achieved

through its prose. This clearly needs explanation, but in the first

instance it would be useful to ask ourselves how such obviously

differentiated mediums as poetry and prose could share an affinity. Let

us therefore make a couple of comparisons. Here is Eliot’s description

of the London fog in ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’:

Virtues of good

“The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes, The yellow

fog that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes Licked its tongue into the

corners of the evening, Lingered upon the pools that stand in drains,

Let fall upon its back the soot that falls from chimneys, Slipped by the

terrace, made a sudden leap, And seeing that it was a soft October

night, Curled once about the house and fell asleep.”

|

|

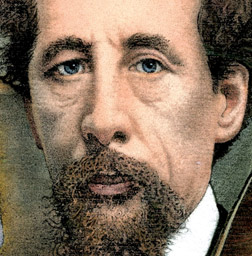

Charles

Dickens |

This description has the virtues of good prose in its lucidity of

expression and the orderliness of its presentation, which fulfils the

structural requirements of a long sentence, such as it is. Yet it is

unmistakably poetry, not only because of its division into lines, its

occasional rhymes and its persistent rhythm, but because of its other

typically poetical features. There is the continuous alliteration and

assonance centred round the letter ‘l’, supplemented by ‘s’, which gives

the description a tactile effect.

Descriptive significance

And the fog is not described literally but metaphorically to the

extent that it is transmogrified into a large, languid cat, even though

the actual word is never used. Thus, the fog makes its impact on us

sensorily as well as mentally and we cannot help feeling that it has a

more than descriptive significance in the poem. This is the evocative

effect of poetry. Now here is another description of fog from Tolkein’s

‘The Lord of the Rings’:

“The hobbits sprang to their feet in alarm, and ran to the western

rim. They found that they were upon an island in the fog. Even as they

looked out in dismay towards the setting sun, it sank before their eyes

into a white sea.

And a cold grey shadow sprang up in the East behind. The fog rolled

up to the walls and rose above them. And as it mounted it bent over

their heads until it became a roof: they were shut in a hall of mist

whose central pillar was the standing stone. They felt as if a trap was

closing about them; but they did not quite lose heart.”

This description is very illustrative, the hobbits being made to feel

trapped in the forbidding architecture, as it were, of the ubiquitous

fog. Yet there is no mistaking this passage for poetry, even if it had

been broken up into lines. It is laid out and developed in neat

syntactical units. The metaphor of the hall with enclosing walls and

roof is an apt representation of the hobbits’ impression of the fog, but

it is purely illustrative as far as the reader is concerned. We note

their experience as part of the story but are not ourselves sensorily

engaged.

Green meadows

For the language is not evocative as in the case of Eliot’s fog, it

is not meant to be nor does it need to be. The excitement for us is in

the flow of the prose narrative. But here is yet another fog to engage

us, this time from the opening chapter of Dickens’ ‘Bleak House’.

“Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits

and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers

of shipping, and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city.

Fog on the Essex marshes, Fog on the Kentish heights. Fog creeping into

the cabooses of collier-brigs, fog lying out in the yards, and hovering

in the rigging of great ships; fog drooping on the gunwales of barges

and small boats.

Syntactical balance

Fog in the eyes and throats of ancient Greenwich pensioners, wheezing

by the firesides of their wards; fog in the stem and bowl of the

afternoon pipe of the wrathful skipper down in his close cabin; fog

cruelly pinching the toes and fingers of his shivering little ‘prentice

boy ion the deck. Chance people on the bridges peeping over the parapets

into a nether sky of fog, with fog all round them, as if they were up in

a balloon, and hanging in the misty clouds.”

This is obviously prose too, yet there is nothing prosaic about it.

We have the narrative momentum, the syntactical balance, the informative

approach and the descriptive detail associated with good prose. Yet

there is another element introduced by the way in which the diction is

chosen and arranged, which is the poetic.

Consider the abrupt opening verb-less sentence, followed by endless

repetitions of the word ‘fog’ and the cascading descriptions of its

multifarious activities.

The entire passage contains only two verbs, ie. in the subsidiary

clauses of the second sentence. The spread and reach of the fog are

conveyed through present participles and prepositions.

These give the succession of word pictures a persistent rhythm that

enacts the relentless progress of the fog. And even though the fog is

not personified, its effects are described in such a plethora of

metaphors, eg. rolling, creeping, pinching, that it is experienced at a

deeper level than Eliot’s fog.

Not our senses only but our feelings are engaged as we, like the

actual victims, recoil from the stupefying impact of its influence. This

is the emotive impact that prose can have when it is incorporates some

of the effects of poetry.

Does this mean that Dickens could have turned this passage of prose

into verse with equal or greater effect? No, because its poetic success

lies precisely in the fact of its composition as prose and its

incorporation as an integral part of the narrative. This becomes clear

as we read on and come across these lines: “And hard by Temple Bar, in

Lincoln’s Inn Hall, at the very heart of the fog, sits the Lord High

Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery.

Objective correlative

Never can there come fog too thick, never can there come muck and

mire too deep, to assort with the groping and floundering condition

which this High Court of Chancery, most pestilent of hoary sinners,

holds, this day, in the sight of heaven and earth.”

As the writing resolves into typically Dickensian prose we realise

that the literal fog of London is a symbol or the objective correlative

of the mental and moral fog that prevails at the heart of England’s

legal system. As the story proceeds we see how far-reaching and damaging

the consequences of the latter are in the lives of the people it

affects, and how aptly it has all been mirrored or prefigured in the

description of the literal fog. But this would hardly have been possible

if Dickens had simply described the London fog in a prefatory poem and

proceeded with his story, since the symbolism would not entered and

enriched the story poetically.

Which brings us to back to our point that the poetic effect of James’

story could not have been achieved other than by prose. It could be

argued, however that the prose of James is a great deal different from

that of Dickens in the fog passage. Not only is it more formal and

correct than that of Dickens, its structure is far more elaborate,

seemingly talking it farther and farther away from poetry.

The Beast

This is all true, and the point could be driven home by refreshing

our memory of James’ style with a look at a sentence from the ‘The

Beast’ that was not quoted last week.

It is from the last chapter after Marcher has caught sight of the

grief-wracked face of the fellow mourner leaving another grave: “What

Marcher was at all events conscious of was in the first place that the

image of scarred passion presented to him was conscious too - of

something that profaned the air; and in the second that, roused,

startled, shocked, he was yet the next moment looking after it, as it

went, with envy,”

What James is saying here is that even though the expression on the

sorrowing man’s face suggested to Marcher that he was being rejected as

a fellow mourner, he could not help envying him.

The question that is bound to be asked is why James has to put it in

so much more complicated a way, and how his expression could be regarded

as being in the least bit poetic. Before we attempt an answer we need to

consider the technical implications of these lines from a sonnet of

Hopkins, which we hope to do next week:

“O the mind has mountains; cliffs of fall Frightful, sheer,

no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap May who ne’er hung there.”

|