|

|

Gender

Forum offers you an opportunity to share your views

and concerns with us. Email to

[email protected]

or mail to Gender Forum, C/O Features Editor, Daily News-

Editorial, Lake House, Colombo. |

Development, freedom and domestic violence

Dr. Dileni Gunawardena

The concept of development as freedom is a key concept in the

writings of Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen who has had a considerable

influence on the way we think about development today. Sen argues that

the goal of development should not be about how much we produce (Gross

National Product) or even how much we consume (basic needs) but how free

we are to participate fully in the society in which we live

(capabilities and freedoms).

Yet,

there are many freedoms and capabilities-and their reverse or absence-”unfreedoms”

and capability deprivations—that do not receive sufficient attention in

the discourse on development. One such “unfreedom” that is the current

focus of much-needed attention is “Gender-based Violence.” The Global

Campaign on the 16 days of activism against Gender Based Violence (GBV)

began on November 25, the International Day Against Violence against

Women and ends on December 10, International Human Rights day, in order

to symbolically link violence against women and human rights and to

emphasize that such violence is a violation of human rights. Yet,

there are many freedoms and capabilities-and their reverse or absence-”unfreedoms”

and capability deprivations—that do not receive sufficient attention in

the discourse on development. One such “unfreedom” that is the current

focus of much-needed attention is “Gender-based Violence.” The Global

Campaign on the 16 days of activism against Gender Based Violence (GBV)

began on November 25, the International Day Against Violence against

Women and ends on December 10, International Human Rights day, in order

to symbolically link violence against women and human rights and to

emphasize that such violence is a violation of human rights.

Bina Agarwal and Pradeep Pande in an article titled “Freedom from

domestic violence” (Journal of Human Development 2007) point out that

domestic violence is an extremely pernicious type of “unfreedom”: by

reducing women’s self-confidence and self-respect, it prevents them from

exercising other freedoms such as education and employment, which in

turn reduce their ability to escape violence. Moreover, children who

grow up in homes with domestic violence are more likely to accept (or

practise) domestic violence in their own households when they are

adults.

This column argues that policies and actions to improve economic

opportunities for women should be among the strategies to address gender

based violence. This argument is based on both economic theory and

empirical evidence from studies conducted in the East as well as the

West.

An expert from the Ministry of Health Services in Sri Lanka was

recently quoted in a leading newspaper as saying that

gender-based-violence cuts across all strata: rich or poor, young or

old, newly married or married for a long period of time. His words echo

a 1984 U.S. Attorney General’s Task Force on Family Violence that states

“We must admit that family violence is found at every level of our

social structure.”

While both these statements are true, it is undeniable that domestic

violence is higher among certain categories. There is evidence for this

assertion from studies all over the world. For example, a Bureau of

Justice Report based on national Crime Victimization Surveys in the

United States show that being young, black, poor, and divorced or

separated all increase the likelihood of a woman being the victim of

intimate partner abuse (Rennison and Welchans 2000). According to this

study, women in the lowest income households had 7 times the abuse rates

of those in the highest income households.

|

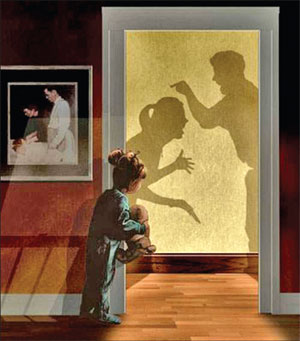

Children who grow up in homes with domestic violence

are more likely to accept domestic violence in their own

households when they are adults. |

Economic theory has an explanation for this. The economics of family

decision making is a branch of economics that is at least fifty years

old. Initial models thought of the family as a single unit, with a

single harmonious objective. Theories based on bargaining models in the

early 1980s assume that family members have conflicting preferences and

have an explicit bargaining structure to resolve conflicts, much like

union workers and employers. Economic models of domestic violence were

first developed in the 1990s using the bargaining model approach. The

main idea in bargaining models is that the outcome or decision depends

on each party’s preference and their ability to exercise that preference

(power) within the household. The best opportunity for each individual

outside the relationship establishes a minimum acceptable position

within the relationship. The model’s prediction is that the stronger the

alternatives outside the marriage, the less likely the threat of

violence.

Improvements in women’s individual economic status enable them to

leave abusive relationships to support themselves. Overall gender

inequality in the community also helps—if a woman lives in an area where

employment opportunities for women are available and female wages are

high, there is a greater credible threat that she could leave the

marriage, and therefore the partner would reduce violence rather than

risk losing her. Outside options could also take the form of services

such as shelters for battered women, welfare services and legal services

to help women with protection orders, child support and custody (Amy

Farmer and Jill Tiefenthaler, Explaining the Decline in Domestic

Violence, Review of Social Economy 1997).

Empirical results from studies in the United States support some of

these predictions. For example, women with higher educational

attainment, employment status, and earnings suffer less violence. Women

with access to fewer resources are less likely to leave abusive

partners. Overall gender inequality is linked to higher rates of abuse

across countries. But all forms of economic independence are not equal

in how they lessen domestic violence.

Two factors are evident in studies in the West as well as in the

East. Firstly, relative differences between partners matter. For

example, if women earn more than their spouses, an increase in earnings

may lead to greater domestic violence. Secondly, having immovable

property (in Kerala, India) or a place to go, such as family, or

shelters (in Santa Barbara, California, ) significantly reduces the

threat of violence and the incidence of physical violence as well.

Agarwal and Panda suggest that apart from educating women on their legal

inheritance rights, states may need to consider housing subsidies for

women subject to domestic violence.

(The writer is a

senior lecturer in Economics, Department of Economics and Statistics,

University of Peradeniya.)

Who will rule the world?

Aditha Dissanayake

World Economic Forum’s sixth annual

Global Gender Gap Report 2011

The World Economic Forum’s study

ranks 135 nations according to progress made in women’s education,

health, economic clout and political empowerment. Last year’s top 10 -

Iceland, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Ireland, New Zealand, Denmark, the

Philippines, Lesotho and Switzerland - continue to hold their spots, but

there was movement below them, notably Cuba climbing back to No. 20.

While 85 percent of the 135 countries

in the survey, representing more than 93 percent of the world’s

population, made some progress in women’s health and education levels,

relatively few showed marked advances for women in economic and

political parity since the first survey came out in 2006.

It is hard to imagine the reaction of most feminists if they read

Piyadasa Sirisena’s novella “Parivarthanaya”, written way back in 1934.

In Chapter six, the judge compares a woman to a gem. “Don’t we have to

safeguard a gem with utmost care? A gem can’t look after itself. A gem

has to be looked after by someone who loves that gem” says the judge and

asks “can there be a worst disaster than when a woman tries to do the

work that should be done by a man and when a man tries to do the work

that should be done by a woman?”.

|

Hard work |

What would the judge say if he had lived today? Would he have been

amazed at how the world had evolved avoiding imminent disaster with more

and more women doing the work traditionally assigned to men while men

have taken on the role of the “housewife?”. In other words, to use the

metaphor the judge uses, are things as disastrous as he predicts with

the ‘gems’ not only looking after themselves but their keepers as well?

Not so. According to statistics given in the Newsweek magazine women

today, “are the biggest emerging market in the history of the planet” so

much so that in another five years most job categories even those which

were traditionally held by men will be filled by women - and the world

surely will be the better for it.

Or will it? Even though the image of the tough minded, high powered

business executive climbing the corporate ladder is becoming

increasingly common not only in the west but in several Asian countries

too women still face problems and limitations and the “average” woman

hardly fits this idealized stereotype.

This is a problem which seems to have existed from the very beginning

of the feminist movement. A Reader’s Digest of the late 1960s reveals

how a panel of doctors and psychiatrists made a study to find out why so

many young women complain of fatigue. Is it psychological? Bad eating

habits? Lack of exercise? Boredom? The panel ultimately determined that

the number one reason women complain of fatigue is because they are

tired. Being a woman is hard work.

Especially if you happen to be living in a developed country.

According to the World Economic Forum’s sixth annual Global Gender Gap

Report 2011, released this October, when it comes to overcoming gender

limitations, poor countries like Lesotho, hold a higher rank (ninth over

all) than the UK or the USA. The UK ranked 33rd - behind such countries

as the Philippines and Mozambique - for economic participation and

opportunity, revealing that even though more women than men go to

university in the UK and the US and tend to outlive them, men still

dominate economic and political leadership. These figures go hand in

hand with research that shows women in the U.S may be working more, and

in greater numbers, but they are still just 3 percent of Fortune 500

CEOs, and make 77 cents on the dollar. “While many developed economies

have succeeded in closing the gender gap in education, few have

succeeded in maximizing the returns from this investment,” the report

states.

There are signs of improvement, though, in other parts of the world,

indicating that you are lucky if you are a woman living in a country

like Cuba, Tanzania, Turkey, Philippines and Sri Lanka. (Philippines,

among the poorest countries in Asia, scored high in all survey

categories of this year’s report, outdoing some of the world’s hottest

economies). Sociologists feel that women in these developing countries

have unexpected advantages when compared with their western

counterparts. Extended families, for example, mean they often have to

grapple less with issues of child care, and feel less fraught over

work/life balance than their Western peers. Due to this unsung freedom

of the developing world some sociologists believe when it comes to

gender limitations these countries have “a clean slate”. According to

Saadia Zahidi, head of the World Economic Forum’s women leaders and

gender parity programme, “Closing the gap is not a luxury good just for

high end companies and countries ... smaller gender gaps are directly

correlated with increased economic competitiveness.”

Klaus Schwab, founder and chairman of the World Economic Forum says

it best, “a world where women make up less than 20 per cent of the

global decision-makers is a world that is missing a huge opportunity for

growth and ignoring an untapped reservoir of potential.”

In other words it is time for change. A tsunami of change, at the end

of which women will rule the world, making it, undoubtedly and

unsurprisingly, a better place.

[email protected]

Your name after marriage:

A great post-wedding game

Frances Ryan

Stay put, go double-barrelled or pick a Brangelina-style mesh? The

options for a non-traditional surname strategy are endless.

There’s a lot in a name. As a form of identification names provide a

fine service, more personable than a numbering system 1 to 7 billion and

one that prevents social interaction from degenerating into “you, the

one with the hair” and a range of vague descriptions. They aren’t

without their problems, though: none more of a quagmire than what

happens to a woman’s name if she gets married.

Though sense would respond with “Nothing, why should it?”, when it

comes to marriage and female autonomy, sense has no place. The reasons

that were used to justify a woman losing her name up until the mid-20th

century are in the modern context, irrelevant. Few couples wake up in a

cold sweat over proving an heir and who will inherit the land and the

town house. Despite what fathers still giving away their daughters

suggests, if you rank people’s reasons for saying “I do”, passing a

woman between estates most likely won’t even make the top three.

In our minds at least, marriage has moved on. The same however can’t

be said for what we do with our names.

Despite an estimated 50 per cent of UK brides bucking the trend, be

it in law or culture, the assumption that a woman will take her

husband’s name persists. You’ll do well to find a newlywed who isn’t

greeted with “Mrs” despite having no intention to be anything but a

“Ms”; the decision to keep her name still perceived as different enough

to be of note.

Faced with the patriarchal status quo and the warm glow of history,

it seems we can’t help but get a little teary. Slotted somewhere next to

the thinking that a wedding is a woman’s chance to (finally) be a

princess, it’s apparently a sign of love to sacrifice the name that’s

been yours since birth. As pop tells young girls a man’s name is the

ultimate gift, some would be concerned for the state of modern romance.

I’d suggest starting with squashed flowers from the local garage and

working up from there.

Ultimately, of course, the pull is tradition. The antiquated past in

this case being a positive to embrace. Tradition, however, can be

abandoned. If indoor toilets and women no longer being tethered to the

sink have taught us anything, there might be even be benefits to it.

Far more fun than thank you cards, there can be no greater

post-wedding game than sitting down, rejecting convention, and figuring

out what you’re going to be called. The obvious option is to keep your

name as it was before. It has the advantage of respecting both genders

as equal, and most importantly allows girls you haven’t spoken to since

school to still be recognisable on social networking sites.

For many there’s an appeal in the change, though, of the sense of

family unit that comes in not only sharing a home but a name. It’s a

strategy of particular use if children come along, allowing you to avoid

the fight between names that usually results in the one enduring

childbirth having theirs consigned to the dustbin of life. Double-barrelling

is a classic for this purpose - though in ducking feminism and entering

straight into class warfare, it isn’t without problems of its own.

Some men have started to take their wife’s name and the world as yet

hasn’t ended. That they have to do it via deed poll rather than the

simple tick of a box offered to women just ensures the law can confirm

they’re indeed weird.

Luckily the newest marital name trend has ensured the long search for

a solution is over. Couples are now “meshing”: blending the key

syllables of both of their surnames to form a brand new sparkling one.

For the romantics, it’s the ultimate union - and allows the fortunate to

discard the shackles of mediocrity and swap Granger and Den for

“Danger”.

Guardian.co.uk |