|

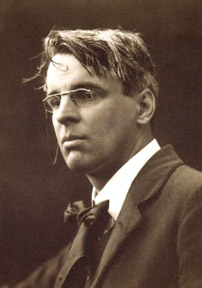

William Butler Yeats:

‘Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry’

The reference in the article on Auden to his elegy on the death of WB

Yeats (1865-1939) was a reminder that we had still to deal with the

latter, an omission that it is now time to make good.

Yeats was an Irishman, but he began his poetic career in the

essentially British Pre-Rapahaelite and Aesthetic tradition represented

by Rossetti, Swinburne and Morris. His early poetry is typical of what

Eliot calls “the vague enchanted beauty” of that tradition. However, by

drawing on Celtic mythology and folklore as well as on the Irish

landscape for inspiration Yeats does achieve a distinctively individual

note, a good example of which is “The Lake Isle of Innisfree”: “I will

arise and go now, and go to Innisfree, And a small cabin build there, of

clay and wattles made...And I shall have some peace there, for peace

comes dropping slow, Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the

cricket sings....I will arise and go now, for always night and day I

hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore...”

|

|

W B Yeats |

What Yeats’ Irishness does for his poetry at this stage is to “give

to airy nothing a local habitation and a name.” Still, we do not feel

that the poetic imagination is working to its potential. It is seemingly

the “fancy” that is taking up the slack and fancy, as suggested by

Shakespeare’s Ariel and confirmed by Coleridge, is bred in the head

rather than in the heart. “Mad” Ireland has not as yet, in the words of

Auden’s elegy, “hurt Yeats into poetry” of the heart, bred out of the

plenitude of emotional experience.

That only happens after Yeats gets involved in the real Ireland of

the present rather than the idealised Ireland of the past. It is then

that the anguish of an unrequited love for a beautiful Irish woman, the

disappointment with Irish politics and the horrors of the Irish civil

war, the frustrations of trying to spearhead an Irish literary revival,

along with the consciousness of growing helplessly old in this maddening

Irish context, all contribute to Yeats’ progressive development into a

major poet. The process starts with “Adam’s Curse”-1904, Maud Gonne

having rejected Yeats and married another:

“I had a thought for no one’s but your ears: That you were beautiful,

and that I strove To love you in the high old way of love: That it had

all seemed happy, and yet we’d grown As weary-hearted as that hollow

moon” Yeats makes us feel his private agony at the failure of love and

beauty as the general fate of accursed humanity. “The Fascination of

What’s Difficult”-1910 reflects the frustrations of theatre management

even in the noble cause of the promotion of Irish drama: “The

fascination of what’s difficult Has dried the sap out of my veins, and

rent Spontaneous joy and natural content Out of my heart....My curse on

plays That have to be set up in fifty ways, On the day’s war with every

knave and dolt, Theatre business, management of men....”

How different this verse is from the dreamy style of “Innisfree.” The

phrasing is tough and sinewy, the idiom and rhythm are those of modern

speech, and the tone is bitter and disillusioned. Yeats never departed

from traditional verse form, notably rhymed iambic pentameter. What he

did was to intensify from within and develop a uniquely individual

poetic that outstandingly proved the axiom: “Le style-c’est l’homme meme

(Style- it is the man himself).” His Irishness became a matter of

expression as well as of subject matter.

The bitterness deepens to despair in the title poem of

“Responsibilities_-1914: as he contemplates the childlessness that

infatuation has cost him and addresses his forefathers: “Pardon that for

a barren passion’s sake, Although I have come close on forty-nine I have

no child, I have nothing but a book, Nothing but that to prove your

blood and mine.” In “Men Improve with the Years”-1916, the bitterness is

tinged with scorn not only for himself but for humanity: “I am worn out

with dreams; A weather-worn, marble triton Among the streams; And all

day long I look Upon this lady’s beauty As though I had found in a book

A pictured beauty....For men improve with the years; And yet, and yet,

Is this my dream, or the truth? O would that we had met When I had my

burning youth! But I grow old among dreams, A weather-worn, marble

triton Among the streams.”

In “Nineteen-Hundred and Nineteen” of the same date, Yeats’ verse

assumes a Shakespearean density and a cynical intensity as he describes

the brutality on both sides occasioned by British reprisals for the

abortive Irish revolt of 1916: “Now days are dragon-ridden, the

nightmare Rides upon sleep: a drunken soldiery Can leave the mother,

murdered at her door, To crawl in her own blood, and go scot-free; The

night can sweat with terror as before We pieced our thoughts into

philosophy, And planned to bring the world under a rule, Who are but

weasels fighting in a hole.”

What we find in these examples is, in Eliot’s words, “that sense of a

unique personality which makes one sit up in excitement and eagerness to

learn more about the author’s mind and feelings.” In consequence, Yeats

achieves the “impersonality of the poet who, out of intense and personal

experience is able to express a general truth; retaining all the

particularity of his experience, to make of it a general symbol.” As in

the case of Blake, there is a terrifying honesty about Yeats’ mature

poetry, and this comes through because of a commensurate technical

accomplishment.

It is the poems that reflect such honest self-expression – and not

some of the more famous poems that rather spuriously draw their

inspiration from magic and occultism (eg. the two “Byzantiums” and “Leda

and the Swan”) - that create genuine value for the reader. “A Prayer for

my Daughter” draws on Yeats’ experience of disappointed love: “May she

be granted beauty and yet not Beauty to make a stranger’s eye

distraught, Or hers before a looking glass, for such, Being made

beautiful overmuch, Consider beauty a sufficient end, Lose natural

kindness and maybe The heart-revealing intimacy That chooses right, and

never find a friend.” What parent would not realise the wisdom of that

prayer from the felicity of its expression?

The context of “Among School Children” is Yeats’ visit to a school as

“a sixty-year-old smiling public man. He imagines his beloved Maud Gonne

as a child and is shaken by the thought of “her present image” as an old

woman “hollow of cheek” and feeding on “shadows.” This gives rise to

meditations on the way old age seems to mock the labours of mothers to

bring forth life and of philosophers to claim that a spiritual

permanence underlies its physical transitoriness. The final stanza is a

supreme example of the “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” that,

according to Wordsworth, should follow “emotion recollected in

tranquility”:

“Labour is blossoming or dancing where the body is not bruised to

pleasure soul, Nor beauty born out of its own despair, Nor blear-eyed

wisdom out of midnight oil. O chestnut-tree, great-rooted blossomer, Are

you the leaf, the blossom or the bole? O body swayed to music, O

brightening glance, How can we know the dancer from the dance?”

The emotional logic of this glorious verse defies paraphrase. Perhaps

Frost’s lines best convey the sense of it: “The fact is the sweetest

dream that labour knows.” The fact, that is, of life in all its

blossoming, chestnut-tree-like, fullness, without any self-defeating

efforts to analyse its complexity and rationalise its ephemeral nature.

“Anything more that (this) truth would have been too much.” This poem is

surely the acme of the poetic achievement that mad Ireland hurt Yeats

into.

|