|

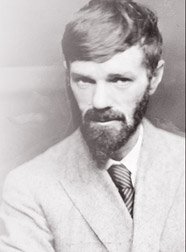

D H LAWRENCE:

In the hands of the unknown God

Referring to the determinants of Blake’s muse earlier in this series

reminded one of D H Lawrence (1885-1930). It is not surprising,

therefore, that the introduction of the latter should recall the former.

Both writers shared a loathing for the oppressiveness of British

civilisation and a passion to reveal a new world of human experience.

Both held that the key to this to lay in the rediscovery of the

instinctive, intuitive side of the human personality .And both pursued

their mission with a religious fervour which led to excesses of

expression both quantitative and qualitative. As TS Eliot said of

Lawrence, he had to write a lot badly in order to write well sometimes.

But those times were enough to put Lawrence among the outstanding poets

and poetic influences of the modern age. Referring to the determinants of Blake’s muse earlier in this series

reminded one of D H Lawrence (1885-1930). It is not surprising,

therefore, that the introduction of the latter should recall the former.

Both writers shared a loathing for the oppressiveness of British

civilisation and a passion to reveal a new world of human experience.

Both held that the key to this to lay in the rediscovery of the

instinctive, intuitive side of the human personality .And both pursued

their mission with a religious fervour which led to excesses of

expression both quantitative and qualitative. As TS Eliot said of

Lawrence, he had to write a lot badly in order to write well sometimes.

But those times were enough to put Lawrence among the outstanding poets

and poetic influences of the modern age.

|

D H Lawrence |

Lawrence believed that the re-integration of the psyche brought about

a new vitality of being, what he called being “man alive”, which led in

its turn to the reforging of the vital relationship between man and his

“circumambient universe”. Thus his poetry often deals with experiences

which provide an insight, to an extent hitherto unrealised in English

poetry, into the unique otherness of inanimate and animate nature.

Emerald trees

“The Enkindled Spring” finds the poet lost in wonder at the

springtime “flaming” of nature around him: “This spring as it comes

bursts up in bonfires green, Wild puffing of emerald trees, and

flame-filled bushes, Thorn-blossom lifting in wreaths of smoke between

Where the wood fumes up and the watery, flickering rushes.

“I am amazed at this spring, this conflagration Of green fires lit on

the soil of the earth, this blaze Of growing, and the sparks that puff

in wild gyration...” Note how the remarkableness of the phenomenon of

spring, usually taken for granted and described in conventional terms,

is captured by the elaborated metaphor of fire.

The wonder and the insight grow deeper in the contemplation of the

“Snake” “A snake came to my water-trough On a hot, hot day, and I in

pyjamas for the heat, To drink there.....

“Someone was before me at my water trough, And I, like a

second-comer, waiting.

“He lifted his head from his drinking, as cattle do, And looked at me

vaguely, as drinking cattle do, And flickered his two-forked tongue from

his lips, and mused a moment, And stooped and drank a little more, Being

earth-brown, earth-golden from the burning bowels of the earth On the

day of Sicilian July, with Etna smoking.”

Rather like Hopkins’ “heart in hiding stirring for a bird in “The

Windhover”, the poet is transfixed by the spectacle of the reptile. But

unlike Hopkins, Lawrence does not compare the creature to himself and

apply it to his own experience.

The abiding effect of the poem is of the strangely dignified

otherness of the snake, its deep connection with “the secret earth”.The

poet’s belated abortive attempt to kill it, which he immediately

regrets, adds to this effect by demonstrating that conventional human

responses to the natural world invariably disrupt man’s vital ties with

it.

Unlike the “spring” poem, this has neither rhyme nor lines of regular

length. And a regularly accentuated rhythm, which even the former poem

had little enough of, is almost completely absent.

Prose-writing

This is, in fact, the first example of “free verse” we have

encountered in this series, and which has increasingly come to

characterise modern poetry..However, as Eliot pointed out, no verse is

entirely free if the poet wants to do a good job, and such is the case

here. Even if there is no conventional verse rhythm, there is

nevertheless a rhythm that is determined by the sense and the cadence of

the words themselves, rather like the rhythm of creative prose-writing

of which Lawrence was a pioneer.

His own view was that “poetry of the present or instant poetry”,

dealing with the immediate experience of life, the living moment, and

emanating from “the instant, whole man”, should not be subjected to the

“static perfection of restricted verse.” The success of this beautiful

poem certainly vindicates that view.

Yet, some of Lawrence’s best poetry is also written in more or less

regular verse, and this is often the case when he is dealing with

personal relationships, where the sense of the past or the future or

both is as present as the present itself.

Such is “In a Boat”: “See the stars, love, In the water much clearer

and brighter Than those above us, and whiter, Like nenuphars...

“When I move the oars, love, See how the stars are tossed, Distorted,

the brightest lost, - So that bright one of yours, love....

“What then, love, if soon Your light be tossed over a wave? Will you

count the darkness a grave, And swoon, love, swoon?”

Satirical verse

Lawrence is partly associated with the early 20th century Imagist

movement which insisted on verbal economy with hard, clear-cut images

that spoke for themselves. In the above poem the larger but fragile

image of the stars in the water is beautifully traced, while Lawrence

with a modicum of comment endows the imagery with the dramatic context

that intensifies the sense of the fragility of human love.

Lawrence’s hatred of British civilisation for its artificiality and

its repression of, or “doing dirt upon”, the true sources of human

vitality, often found expression in satire. His satirical verse is

humourless like Pope’s but lacks the latter’s grace, it is serious like

Johnson’s but without his urbanity.

These are compensated, however, by devastating psychological insight.

Consider this from “How Beastly the Bourgeois Is.” “Isn’t he handsome?

Isn’t he healthy? Isn’t he a fine specimen? Doesn’t he look the fresh

clean Englishman, outside?.....

“Oh, but wait! Let him meet a new emotion, let him be faced with

another man’s need, Let him come home to a bit of moral difficulty, let

life face him with a new demand on his understanding And then watch him

go soggy, like a wet meringue. Watch him turn into a mess, either a fool

or a bully...” Although Lawrence’s particular bugbear was the British

specimen, the ubiquity of this species in all cultures is only too

evident.

Ideal experience

Lawrence’s most famous poem is probably “Piano”, which shows that,

for all his vaunted commitment to the the demands of the present, he was

not immune to the power of nostalgia. Who among us, too, has not

experienced that “The glamour Of childish days is upon me, my manhood is

cast Down in the flood of remembrance, I weep like a child for the

past.”

In fact, as this and some of the other examples above show, Lawrence

wrote his finest poetry when he realised that his own limitations often

brought him in conflict with the ideal experience of life he so

restlessly sought. The greatest limitation he had to come to terms with

was his impending death (of tuberculosis).

This is why in “Shadows” he seems at last to have found peace in

realising that, no longer able to come to his own salvation through

being “man alive’, he was now, whether he lived or died, in the hands of

a hitherto unknown God.

It begins, “And if to-night my soul may find her peace In sleep, and

sink in good oblivion, And in the morning wake like a new-opened flower

Then I have been dipped again in God, and new created.

And it ends, ”Then I must know that still I am in the hands of the

unknown God, He is breaking me down to his own oblivion To send me forth

on a new morning, a new man.” |