Distressed hearts

In the shade of the house, in the sunshine on the river bank by the

boats, in the shade of the sallow wood and the fig tree, Siddhartha, the

handsome Brahmin's son, grew up with his friend Govinda.

The sun browned his slender shoulders on the river bank, while

bathing at the holy ablutions, at the holy sacrifices. Shadows passed

across his eyes in the mango grove during play, while his mother sang,

during his father's teachings, when with the learned men. Siddhartha had

already long taken with Govinda and had practiced the art of

contemplation and meditation with him. Already he knew how to pronounce

Om silently - this word of words, to say it inwardly with the intake of

breath, when breathing out with all his soul his brow radiating the glow

of pure spirit. Already he knew how to recognize Atman within the depth

of his being, indestructible, at one with the universe.

|

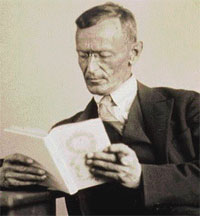

Hermann Hesse |

There was happiness in his father's heart because of his son who was

intelligent and thirsty for knowledge; he saw him growing up to be a

great learned man, a priest, a prince among Brahmins.

There was pride in his mother's breast when she saw him walking,

sitting down and rising; Siddhartha - strong, handsome, supple-limbed,

greeting her with complete grace.

Love stirred in the hearts of the young Brahmin's daughters when

Siddhartha walked through the streets of the town, with his lofty brow,

his king-like eyes and his slim figure.

Govinda, his friend, the Brahmin's son, loved him more than anybody

else. He loved Siddhartha's eyes and clear voice. He loved the way he

walked, his complete grace of movement; he loved everything that

Siddhartha did and said, and above all he loved his intellect, his fine

ardent thoughts, his strong will, his high vocation. Govinda knew that

he would not become an ordinary Brahmin, a lazy sacrificial official, an

avaricious dealer in magic sayings, a conceited worthless orator, a

wicked sly priest, or just a good stupid sheep amongst a large herd. No,

and he, Govinda, did not want to become any of these, not a Brahmin like

ten thousand others of their kind.

He wanted to follow Siddhartha, the beloved, the magnificent. And if

he ever became a god, if he ever entered the All-Radiant, then Govinda

wanted to follow him as his friend, his companion, his servant, his

lance-bearer, his shadow.

That was how everybody loved Siddhartha. He delighted and made

everybody happy.

But Siddhartha himself was not happy. Wandering along the rosy paths

of the fig garden, sitting in contemplation in the bluish shade of the

grow, washing his limbs in the daily bath of atonement, offering

sacrifices in the depths of the shady mango wood with complete grace of

manner, beloved by all, a joy to all, there was yet no joy in his own

heart. Dreams and restless thoughts came flowing to him from the river,

from the twinkling stars at night, from the sun's melting rays. Dreams

and a restlessness of the soul came to him, arising form the smoke of

the sacrifices, emanating form the verses of the Rig-Veda, trickling

through from the teachings of the old Brahmins.

Siddhartha had begun to feel the seeds of discontent within him. He

had begun to feel that the love of his father and mother, and also the

love of his friend Govinda, would not always make him happy, give him

peace, satisfy and suffice him. He had begun to suspect that his worthy

father and his other teachers, the wise Brahmins, had already passed on

to him the bulk and best of their wisdom, that hey had already poured

the sum total of their knowledge into his waiting vessel; and the vessel

was not full, his intellect was not satisfied, his soul was not at

peace, his heart was not still.

The ablutions were good, but they were water, they did not wash sins

away, they did not relieve the distressed heart. The sacrifices and the

supplication of the gods were excellent - but were they everything? Did

the sacrifices give happiness? And what about the gods? Was it really

Prajapati who had created the world? Was it not Atman, He alone, who had

created it? Were not the gods forms created like me and you, mortal,

transient? Was it therefore good and right, was it a sensible and worthy

act to offer sacrifices to the gods? To whom else should one offer

sacrifices, to whom else should one pay honour, but to Him, Atman, the

Only One? And where was Atman to be found, where did He dwell, where did

His eternal heart beat, if not within the Self, in the innermost, in the

eternal which each person carried within him? But where was this self,

this innermost? It was not flesh and bone, it was not thought or

consciousness.

That was what the wise men taught. Where, then, was it? To press

towards the Self, towards Atman - was there another way that was worth

seeking? Nobody showed the way, nobody knew it - neither his father, nor

the teachers and wise men, nor the holy songs. The Brahmins and their

holy books knew everything, everything: they had gone into everything -

the creation of the world, the origin of speech, food, inhalation,

exhalation, the arrangement of the sense, the acts of the gods. They

knew a tremendous number of things but was it worth while knowing all

these things if they did not know the one important thing, the only

important thing?

Many verses of the holy books, above all the Upanishads of Samaveda,

spoke of this innermost thing. It is written: 'Your soul is the whole

world.' It says that when a man is asleep, he penetrates his innermost

and dwells in Atman. There was wonderful wisdom in these verses; all the

knowledge of the sages was told here in enchanting language, pure as

honey collected by the bees. No, this tremendous amount of knowledge,

collected and preserved by successive generations of wise Brahmins,

could not be easily overlooked. But where were the Brahmins, the

priests, the wise men, who were successful not only in having this most

profound knowledge, but in experiencing it?

(An excerpt from Hermann Hesse's Siddhartha - translated from German

into English by Hilda Rosner) |