|

Short Story:

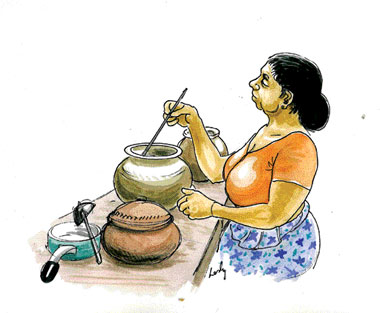

Lucy Nona becomes a cook

A F Dawood

I was posted to a school in Batticaloa. It was a punishment transfer

soon after the Government came to power. I travelled by the night train

to Batticaloa and it was a very tedious journey; I reached there before

dawn.

As it was dark I dawdled in the station on one of the benches,

killing time. As the first streak of light appeared, I came out of the

station and surveyed the area. There were two or three roads, lonely and

narrow, and in one corner of the street was a kiosk and a hurricane lamp

hung there.

I crossed over to this kiosk and saw about five Tamil men jabbering

in Tamil. I was a stranger in my own country because I was not able to

converse in Tamil. An old woman who was baking hoppers saw me and asked

in Tamil.

Doray, enna veynum? (sir, what do you want?) I smiled but did not

respond. I wanted to find out where my school was situated but nobody

could help me as they did not know Sinhala. After a meal of hoppers and

a cup of tea, I stepped out and it was seven in the morning. I walked

along the desolate street skirted by fields and bare lands; there were

no dwellings.

A man carrying a bundle of straw was coming from the opposite

direction and when he approached me, I asked him the direction of my

school. He could not speak Sinhala and he simply stretched out his hand

to show the direction. I did not understand what he said.

Having walked for more than half an hour, I met another man and he

too was not in a position to help me. I lost all hope of meeting someone

who could speak my language. I simply traversed, passing fields and

brown earth of sparse vegetation, some places dotted with bijou huts and

I thought I was on a wild goose chase.

I would have walked about three kilometres when I met another man

clad in white verti (white cloth), coming from the opposite direction. I

greeted him with vanakkam and he reciprocated my greeting, flashing a

smile.

He was conversant in Sinhala. In fluent Sinhala he told me that I was

closer to the school and advised me to walk another half a kilometre. I

resumed my weary walk, now and then mopping up my face of perspiration.

At last I reached a dilapidated building of mud wall and thatched

roof and its rickety wooden gate was barred (closed) with a corroded

chain. A signboard in Tamil was fixed to the mud wall. I thought it must

be the name of the school.

Strangely, not a student was sighted. Opposite to the school was a

ramshackle boutique with thatched roof. An old woman, seemingly in her

sixties, and a boy of fifteen years were weaving cadjan leaves. The

woman saw me standing near the gate.

“Ah! sir, mey iskoleta patweem deela vaagey. Koluwa, athulata gihin

kiyaapang sir kenek awilla kiyala “ (I think you have got an appointment

to this school. Go inside and tell a teacher has come)

The boy crept through the fence and ran inside, “Ammata hondata

Sinhala Katakaranna puluwan ney.” (You can talk Sinhala well) I told

her. “Mama Sinhala, mahatmaya, demala noweyi

Two Tamil teachers came to welcome me. They took me to their lodging

which I had to share with them. The lodging was a wattle and daub

structure with thatched roof and was adjoining the school which

comprised about one hundred and fifty students and five teachers

including me. The two teachers who met me for the first time were

Tambimuttu and Vairanathan. About one hundred and fifty yards away from

the lodging was the well.

“Where do you have your meals?”

“There’s a boutique opposite the school run by Lucy Nona. We take our

meals from there.” Tambimuttu said. “Why no school today?”

“Today it was raining here till seven in the morning; so the children

didn’t come and we have a holiday.” Tambimuttu explained laughingly. By

eleven in the morning, the two teachers took me to Lucy Nona’s kiosk

opposite the school. The old woman offered us plain tea in crude

utensils and each a piece of jaggery; I sat hesitantly on a wonky bench

and drank the tea.

“Aney, alut gurumahatayaata mehe honda putu naha” (Oh new teacher,

there’s no good chairs here) On the following day I met the other two

teachers, Selvarajah and Tawamani, the only female teacher in the

school; all the four teachers were very kind and cordial to me.

I was able to work in the school as English assistant only for six

months because violence erupted in Batticaloa and the LTTE gave orders

to evacuate the area.

Curfew was imposed throughout and the school remained closed. With

the LTTE threat mass exodus of people, Sinhala, Tamil and Muslims, began

in Batticaloa. The whole area looked deserted but Lucy Nona did not

move. She continued her weaving and a little bit of farming.

“Lucy Nona yanne nedda?” (Lucy Nona, you’re not going?)

“Mame koheda yanne, mung mehe avilla godak kal.” (where shall I go, I

came here a long time ago)

“Lucy Nonage gama?” (Where’s your village, Lucy Nona?)

Then she told a very pathetic story. She told that she was befriended

by an Indian man who had promised her to look after her well. He had

shown her jewellery and had enticed her. So she had eloped with him from

Kandy a long time ago and settled down in Kurunegala.

Later she had come to know that the Indian man had women in every

part of the island. So she had left him fourteen years ago and had come

to Batticaloa with her one-year old infant.

“Lucy Nonata Kawuruth nadda mahalu vayase balaganna?” (Lucy Nona, you

don’t have anyone to look after you in old age?)

“Okkomala tarahai mang Indian karayaath ekka penala giyaa kiyala”

(They’re all angry with me because I eloped with an Indian)

“Ehenam api giyoth Lucy Nona taniwenawaa.” (Then when we all go you

will be alone)

“Kamak naha demala koti maava marala dai.” (Doesn’t matter, Tamil

tigers will kill me)

It is fifteen years since leaving Batticaloa. I was teaching in a

school in Colombo. One day after my lunch I stepped out of a hotel when

a car pulled up near me. The man at the wheel put out his head through

the window and smiled. I looked hard at him but could not recognize him.

“Hello! Can you recognize me?” I was trying to recollect.

“I’m Tambimuttu,” he said, “from Krishna Vidyalaya, Batticaloa.” At

once memories of my first day in that school flashed in my mind. “Oh!

Tambimuttu, you’ve changed a lot. What’re you doing now?”

“I am doing business.”

“So you’re not in Batticaloa?”

“I’m still in Batticaloa, but not teaching.” Tambimuttu said.

“What happened to our school?”

“When all the people left there were no children. So the school

remained closed. The LTTE captured the school and converted it to a

bunker.”

“Then what happened to Lucy Nona? Did she leave Batticaloa?”

“No, no, she is there. The LTTE captured her.”

“Oh what a pity. I told her to leave when trouble broke then?”

“No Derrik, she is well off now; there’s no need to feel sorry about

her.” Tambimuttu told me.

“She is still running that rickety boutique?”

“No. Lucy Nona became a cook for the LTTE.”

(This story was

written before LTTE terrorism was vanquished) |