Sunil Santha: The keynote of hela music

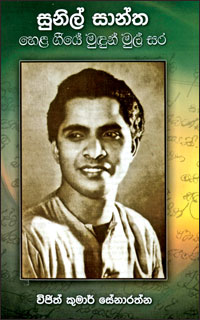

Sunil Santha: Hela Geeye Mudun

Malsara

Author:

Vijith Kumar Senaratne

It is indeed a sad irony of Sri Lankan musical criticism that great

local artistes are sung only posthumous accolades. Thirty years have

gone by since the death of Sunil Santha and we yet await an in-depth

study of the musical corpus left behind by this genius. It was Tissa

Abeysekera who embarked upon an initial assessment of Sunil's work and

his considered opinion that 'Sunil Santha remains the greatest Sinhala

musician of the twentieth century' seems to sound a veritable judgement

on those who neglected this musician, attempting to cast him and his

music into oblivion.

Sunil Santha set out on an admittedly ambitious project in the mid

20th century to develop an authentic Sinhala music based on the concepts

expounded by his ideological guru, Cumaratunga Munidasa, who strode the

Sinhala literary world like a colossus during the early part of the 20th

century. That Sinhala poetry must be the basis of Sinhala music was

Cumaratunga's main thesis.

Thus Sunil Santha sought the cooperation of the highly erudite poets

of the Hela school to provide him lyrics in the idiom of Classical

poetry, following the rules of ancient prosody. There are critics who

would deem this very fact as having been detrimental to the full

flowering of Sunils' talents. Indeed, his own lyrical ability was

remarkable. However it was in the composition of the music itself that

the real problem came to light.

There was no authentic folk tradition or musical form which could be

used as melodic templates to create new Sinhala songs. The pirith chant

and the rustic folk songs which many would have thought to be obvious

and rational choices for melodic templates were rejected by Sunil Santha

as being inadequate and unusable for the genesis of a truly contemporary

art form. His predecessors in the field had sought to ground themselves

on melodic styles of Rabindra Sangeet and North Indian Raga music. To

this dilemma, Sunil Santha gave no clear, fully conceptualized answer.

Instead, it appears as if he experimented with all available forms of

musical traditions prevalent in the country at that time.

This included authentic folk songs, Raga based music, Rabindra

Sangeet, English light music, Christian hymnology and even the

undeservedly despised Kaffringa songs, all providing thematic

inspiration for the composition of his music.

In this endeavour, the specifically Sinhala flavour was to abound in

his creations, chiefly because of the linguistic purity of the lyrics

and his own inherent Sinhala genius intensely nurtured in the Hela

movement of Cumaratunga Munidasa.

Sunil Santha always realized that his were but the first steps

towards the goal of creating a body of modern music with a Sri Lankan

identity. His were the pioneering efforts to halt the desertification of

the Sinhala musical field, a threat that has been fortunately averted

thanks to the endeavours of a handful of dedicated Sinhala musicians.

Sunil Santha was highly trained in the Ragadhari musical tradition.

He had drunk deep from that stream at Bhatkande College, earning two

degrees in the highest rank of merit.

However, his sharpest criticisms were directed against local

exponents of Raga music and he did not baulk at derogatory remarks with

uncharacteristic lack of sympathy, equating their singing to the

nocturnal howling of cats and dogs. It was not the Ragadhari system that

he objected to, but the unaesthetic performance of it. Even in India,

not all would accept the current renditions of Raga as ideal. Prof.

Ediriweera Sarathchandra records in his reminiscences an anecdote from

the time he spent in Tagore's Shanthinikethan, sounding very much like

Sunil Santha's remarks on some performances of Raga music:

"In Shanthinikethan itself, there are differences of opinion about

the relative value of Classical and modern music. I remember the first

concert I attended at Shanthinikethan. There were several items of

Bengali, Hindustani, Tamil and even Sinhalese songs, including

instrumental items.

At the end of the program, there was to be a Classical Hindi song by

the new Professor of classical music, a Sangeeta Visharadha of the

Lucknow College of Music. Half the crowd got up and walked away even

before the item began. The alap went on for about half an hour without

much hope of ending. I was anxious to listen to a good rendering of a

classical song and was eagerly awaiting the actual raga after the alap

was over. The fellows go on howling ah...ah....ah... There is no end to

their ah... ah.... ah...s".

Sunil Santha's musical compositions, therefore, are rich in thematic

content drawn from diverse musical traditions but emerging as a fresh

and dynamic musical system in its own right, propelled by the potent

creative force of the composer. Sunil's music was influenced by many

sources but he was a slave to none. Sunil Santha's melodies are uniquely

his. They are deceptively simple, rarely travelling out of the bounds of

the diatonic scale. Although critic complain that his music lacks

complexity, that is an illusion of superficial analysis. These melodies

make abundant use of the 'shrutis' (ie. notes interspersed inbetween

notes of the chromatic scale), so that the accurate melody cannot really

be reproduced precisely on any of the usual musical instruments. Attempt

to play the first two lines of the ever popular Kokilayange song and you

will be convinced of this fact. This was brilliantly perceived by Tissa

Abeysekera when he worked on these melodies with the musician Piysiri

Wijeratne. Thus, there is a melody within the melody. The composer's

musical ability sometimes shows up in greater measure in the gracefully

light but melodically rich songs such as Vasantha Geethaya and Lanka

Lanka.

Vijith Kumar Senaratne's anthology of nine pieces written by him over

a period of several years, is a welcome contribution to Sunil Santha

studies as it records the personal journey with the singer from 1966

right up to the time of his demise. Little known facts of Sunil Santha's

chequered life emerge to add vibrancy and colour to the artist it

portrays. Specially interesting are Sunil Santha's comments on more

modern singers as these are not commonly known to any but his closest

associates.

Senaratne is no mean critic. His analysis of the music of Kethaki

Patali shows a deep musicological knowledge. A great many other songs

are briefly analysed and notes of appreciation are constructed in the

article Athamebula, which I myself appreciate most. Senaratne's

extensive knowledge of Sunil Santha's musical compositions enables him

to highlight the later experimental creations which Sunil Santha

broadcast in programs such as Madhura Madhu. These have received scant

notice from musical analysts of Sri Lanka and I believe that Senaratne's

book should help 'popularise' these gems of art music as they are never

aired nowadays and are not available on commercial CDs. Songs in the

films Rekawa and Sandeshaya are modern classics, but how many know that

the melodies were created by Sunil Santha?

Senaratne is fearless in his criticism (as much as his hero Sunil

Santha). His analysis of the vocalization of Sunil songs by other

artists is true enough. Almost never is a song rendered so that its full

glory is brought out. Senaratne's comments on Rohana Weerasinghe's

opinion of Sunil Santha and his response to the critique regarding the

song Kukulu Heavilla many seem uncharitable to some, but he speaks

frankly because he speaks truly from his heart.

It is appropriate that Ivor Dennis, the erstwhile devoted pupil of

Sunil Santha has received due mention in the book. I am personally aware

that even in his advanced years, Ivor Dennis' powerful and sensitive

rendition of Sunil songs is considered by some to surpass even the

recordings of the great maestro himself.

Perhaps the most important message of Vijith Kumar Senaratne's book

is that Sunil Santha's mission was not fruitless; that the musical

corpus he bequeathed to the Sri Lankan musical heritage has yet to

receive its due place in contemporary Sinhala culture, as these songs

are timeless and therefore cannot and should not be compartmentalised as

belonging to any era. Sunil Santha was not merely a singer of immensely

popular songs, but a creative artist whose work must be accorded the

highest recognition due to art music, an artist who will be commemorated

by future generations as a legend. In the present context, the part we

have to play would be to initiate a critical study of Sunil Santha's

music, and our major duty would lie in preserving for posterity the fast

disappearing rare recordings of the maestro. Sunil himself died

harbouring the belief that the tapes of his new songs had been

destroyed. This, we know, is not true. The time is truly ripe for a

retrieval and a revival.

Dr. Ruvan Ekanayaka |