The Growth illusion

DAVID C. KORTEN

To address

poverty, economic growth is not an option: it is an imperative.

- Mahbub ul Haq, former World Bank vice president

Economic growth

provides the conditions in which protection of the environment can be

best achieved, - International Chamber of Commerce

Perhaps no single idea is more deeply embedded in modern political

culture than the belief that economic growth is the key to meeting most

important human needs, including alleviating poverty and protecting the

environment.

Anyone who dares to speak of environmental limits to growth risks

being dismissed out of hand as an antipoor doomsayer. Thus most

environmentalists call simply for "a different kind of growth" although

it is seldom evident what kind it would be.

Nobel laureate economist Jan Tinbergen and his distinguished

colleague Roefie Hueting point out that there are basically two ways for

an economy to grow by our current mode of reckoning. One is to increase

the number of people employed.

|

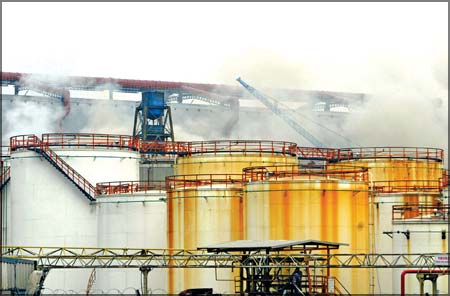

Heavy industries consume a substantial portion of our

nonrenewable energy reserves. |

The other is to increase the labour productivity - the value of

output per worker of those already employed. Historically, increases in

labour productivity have been the most important source of growth.

About 70 per cent of this productivity growth has been in the 30 per

cent of economic activity accounted for by the petroleum, pertochemical,

and metal industries; chemical intensive agriculture; public utilities;

road building, transportation; and mining-specifically, the industries

that are most rapidly drawing down natural capital, generating the bulk

of our most toxic wastes and consuming a substantial portion of our

nonrenewable energy reserves.

Furthermore, the more environmentally burdensome ways of meeting a

given need are generally those that contribute most to the gross

national product (GNP). For example, driving a mile in a car contributes

more to GNP than riding a mile on a bicycle.

Turning on an air conditioner adds more than opening a window.

Relying on processed packaged food adds more than using natural foods

purchased in bulk in reusable containers. We might say that GNP,

technically a measure of the rate at which money is flowing through the

economy, might also described as a measure of the rate at which we are

turning resources into garbage.

We could expend a lot of effort on the probably unrealistic goal of

making GNP go up indefinitely without creating more garbage. But why not

instead concentrate on ending poverty, improving our quality of life,

and achieving a balance with the earth? These are achievable goals-if we

can free ourselves from the illusion that growth is the path to better

living.

A disillusioned economist

In 1954, R.A. Butler, the British chancellor of the Exchequer, made a

speech to a Conservative Party conference in which he pointed out that a

3 percent annual growth rate would double the national income per capita

by 1980 and make every man and woman twice as rich as his or her father

had been at the same age. The speech proved to be a turning point in

British life.

Previously, national goals had been set in terms of specific targets,

such as building 300,000 houses a year or establishing a national health

service. Henceforth, the primary goal would be economic growth. The

ideological debate between Left and Right as to how a fixed pie would be

distributed was largely defused. Attention centered on how to increase

the size of the pie.

In 1989, Irish economist Richard Douthwaite set out to document the

benefits of the subsequent doubling of Britain's per capita income. In

his own words.

Problems only arose when I attempted to identify what they (the

benefits) were, especially as it quickly became apparent that almost

every social indicator had worsened over the third of a century the

experiment had taken.

Chronic disease had increased, crime had gone up eight fold,

unemployment had soared and many more marriages were ending in divorce.

Almost frantically I looked for gains to set against these losses which,

in most cases I felt, had to be blamed on growth.

Eventually . . . I gave up. The weight of evidence was overwhelming:

the unquestioning quest for growth had been an unmitigated social and

environmental disaster. Almost all of the extra resources the process

had created had been used to keep the system functioning in an

increasingly inefficient way.

The new wealth had been squandered on producing pallets and

corrugated cardboard, nonreturnable bottles and ring-pull drinks cans.

It had built airports, supertankers and heavy goods lorries, motor ways,

flyovers and car parks with many floors.

It had enabled the banking, insurance, stock brokering,

tax-collecting and accountancy sector to expand from 493,000 to

2,475,000 employees during the thirty-three years. It had financed the

recruitment of over three million people to the "reserve army of the

unemployed." Very little was left for more positive achievements when

all these had taken their share.

We might apply a similar test to the fivefold increase in global

output since 1950. The advocates of growth persistently maintain that

economic growth is the key to ending poverty, stabilising population,

protecting the environment, and achieving social harmony.

Yet during this same period, the number of people living in absolute

poverty has kept pace with population growth: both have doubled. The

ratio of the share of the world's income that went to the richest 20

percent and that which went to the bottom 20 per cent poor has doubled.

And indicators of social and environmental disintegration have risen

sharply nearly everywhere. Although economic growth did not necessarily

create these problems, it certainly has not solved them.

The limits of growth

Few would dispute that there has been real and consequential human

progress over the past several centuries and that advances in technology

and the consequent productivity increases have resulted in real gains in

human well-being.

At the same time, as this chapter elaborates, there is little basis

for assuming that economic growth, as we currently define and measure

it, results in automatic increases in human welfare. As British

economist Paul Ekins points out, it is possible to conclude that a

particular instance of growth has been a good thing only by:

* Showing that the growth has taken place through the production of

goods and services that are inherently valuable and beneficial;

* Demonstrating that these goods and services have been distributed

widely throughout the society; and

* Providing that these benefits outweigh any detrimental effects of

the growth process on other parts of society. Our measures of GNP make

no such distinctions. Indeed, a major portion of what shows up as growth

in GNP is a result of:

* Shifting activities from the nonmoney social economy of household

and community to the money economy with the consequent erosion of social

capital;

* Depleting natural resources stocks - such as forests, fisheries,

and oil and mineral reserves - at far above their recovery rates; and

* Counting as income the costs of defending ourselves against the

consequences of growth, such as disposing of waste, cleaning up toxic

dumps and oil spills, providing health care for victims of

environmentally caused illnesses, rebuilding after floods resulting from

human activities such as deforestation, and financing pollution-control

devices.

Depreciation

Standard financial accounting deducts from income an allowance for

the depreciation of capital assets. The economic accounting systems by

which economic growth is measured make no comparable adjustment for the

depletion of social and natural capital. Indeed, economic accounting

counts many costs of economic growth as economic gains, even though they

clearly reduce rather than increase our well-being.

The results are sometimes ludicrous. For example, the costs of

cleaning up the Exxon Valdez oil spill on the Alaska coast and the costs

of repairing damage from the terrorist bombing of the World Trade Center

in New York both counted as net contributions to economic output. By

this distorted logic, disasters that are tragic for the people and the

environment are often counted as good for the economy.

In their book For the Common Good, Herman Daly and John Cobb Jr.

reconstruct the national income accounts for the United States from 1960

to 1986, counting only those increases in output that relate to

improvements in well-being and adjusting for the depletion of human and

environmental resources. The result is an index of economic welfare

rather than gross output.

Their index reveals that, on average, individual welfare in the

United States peaked in 1969, then remained on a plateau and fell during

the early and mid 1980s. Yet from 1969 to 1986, GNP per person went up

by 35 per cent, and fossil fuel consumption increased by around 17 per

cent. The main consequence of this growth has been that most of us are

working harder to maintain a declining quality of life.

(Extracted from Daul C. Karten's when cooperation rule the world) |