|

|

|

Release your mind

Let go the past. Let go the future. Let go the present. Crossing

to the farther shore of existence, with mind released from

everything, do not again undergo birth and decay.

- Tanha Vagga - The Dhammapada |

Understanding akusala and kusala

Kingsley Heendeniya

KUSALA: The words akusala, kusala and kamma are probably the

commonest words familiar to every Buddhist.

They are also the words commonly mistranslated and popularly

misunderstood with dire consequences or miccaditthi which the Buddha

says is the worst akusala kamma, the single most of impediment to

progress in Dhamma. It shuts the door to freedom from dukkha. Why is

that?

Sammaditthi is the opposite of miccaditthi where ditthi means ‚Äėwrong

view’. Sammaditthi is right view, seeing the true teaching, gaining

insight of its content, intent and meaning.

Venerable Sariputta, when teaching bhikkhus in higher training [sekha]

said: ‚ÄėFriends, in what way is a noble disciple one of right view, whose

view is straight, who has perfect confidence in the Dhamma, and has

arrived at this true Dhamma?’

They answered: ‚ÄėIndeed, friend, we would come from far away to learn

from the venerable Sariputta the meaning of this statement. It would be

good if the venerable Sariputta would explain the meaning of this

statement.

Having heard it from him, the bhikkhus will remember it.’ Then

venerable Sariputta, the foremost disciple of the Buddha, delivered a

deep discourse on sixteen ways to arrive at Sammaditthi. [MN 9]. He

began by describing akusala and kusala kamma.

“When a noble disciple understands akusala and kusala and their

origin ... one has arrived at this true Dhamma. Killing living beings,

stealing, sensual misconduct; false, malicious, harsh speech, gossip;

covetousness, ill-will and wrong view is akusala.

They originate from greed (lobha), aversion (dosa) and delusion (moha).

Kusala is abstention from these ten actions and intentions, originating

in non-greed (alobha), non-aversion (adosa) and non-delusion (amoha).

When a noble disciple has thus understood the akusala and kusala

together with their root cause, he entirely abandons addiction to lobha,

dosa and moha.

Consequently, he extirpates the conceit‚Äô ‚ÄėI-am‚Äô (asmi mana), and by

abandoning nescience (avijja) and arousing true knowledge (vijja) he

here and now makes an end of dukkha. In this way too a noble disciple is

one of sammaditthi...and has arrived at this true Dhamma.‚ÄĚ

Elsewhere he says: ‚ÄėJust as the dawn heralds and foretells the rising

of the sun, right view heralds and foretells penetration of the four

noble truths, as they actually are.’ In the Mahahattipadomasutta, he

says: ‚ÄėJust as the footprint of the elephant can include in it the

footprint of any animal, all kusala things are included in the four

noble truths.’

These statements (paraphrased) highlight the great importance and

relevance of correctly understanding akusala and kusala.

Four concepts can immediately be noted: (a) it is essentially about

intention (cetana), (b) akusala is defined in positive terms or

intention (e.g. killing), (b) kusala is in negative terms, abstaining

specified intention or action (e.g. not-killing) and (c) both originate

in either presence or absence of lobha, dosa, moha (kilesa).

The kilesa in consciousness attenuate in the ordinary man with

progressive abstention. All are extirpated in the arahat, from

overcoming the root, the conceit ‚ÄėI am‚Äô. It follows that kusala is

action that does not produce arising of (new) action or intention. There

is no one by whom or for whom intentions arise.

‚ÄėThe arahat has lived the holy life, done what had to be done, there

is no more work to do, there is no more of this to come.’ But the

householder cannot extirpate the root conceit ‚ÄėI am‚Äô or asmi mana here

and now to make an end of dukkha. That is why akusala/kusala contains

these four concepts. Let me explain further.

Kusala or ethical actions are means to an end. But we often confuse

means with ends. Why help an old lady cross-road? For reward? How make a

choice in intentional duality to ignore her (akusala) or help her (kusala)?

Intention is actually intentional intention, and negative: ‚Äėignore

her‚Äô in immediate consciousness denying the intention ‚Äėhelp her‚Äô in

reflexive consciousness or the other way around - the present in the

absent, or the absent in the present; and whichever, the relationship of

akusala/kusala is the same.

Consciousness is intention. The intention or reason for ethical

action is not self- evident. It is learnt. Venerable Sariputta spelled

out ten things that should not positively be done, and conversely,

negative to be done.

We can accept or reject his advice, all or some. They are not divine

putative imperatives. And this is exactly the point at which the words

akusala and kusala are misinterpreted.

What is the difference in the ethics of killing an ant and killing an

elephant? The simplest answer is that there is no difference - the

intention is to kill a living being. We can assume that there is

magnitude in the result or outcome (vipaka), if any.

So what has the Buddha advised in this regard? ‚ÄėDo not think of the

ripening of action - it will make you go mad!’ The permutations of

results of variables in intentions, past, present (and future) are not

determinable. It is impossible to know the discrete result of a specific

intent.

It is impossible to know the result waiting (in this life or in

next). It is impossible to know what was done in the past, how much is

ripened, how much reaped and how much remains to ripen. (Culadukkakkhandasutta

and elsewhere).

The great stress and emphasis in the Dhamma is to know for oneself.

The aim is to go at a tangent to re-becoming, make effort here and now

to escape re-becoming. It is a do-it-yourself-teaching.

The kilesa are defilements in one’s consciousness. They have to be

deleted, in part or full, by consciousness, through consciousness (cetana)

trained, guided, developed and maintained as instructed by the Buddha,

from complete confidence in him and in his teaching (aveccappasada).

The implication is that to do this yourself, one should have skill,

energy and resolve to understand, penetrate, practice and experience the

Dhamma. Herein is the clue to correctly understand akusala and kusala.

Note that it is akusala that is first mentioned and explicitly

defined. Commonly, akusala/kusala is translated ‚Äėunwholesome/wholesome‚Äô,

understood in terms of demerit/merit, bad/good, implying collecting,

accruing, storing, forwarding, transferring - not abstaining,

abandoning, not letting go but the opposite of the Teaching.

This is a grave misdirection. The mistranslation has done great harm

such as when rites and observances - lighting 84,000 oil lamps, saving

animals from slaughter, ceremonial gifting - are promoted as ‚Äėwholesome‚Äô

kusala kamma notwithstanding that such intentions (silabbata paramasa)

are the third of four things holding back (upadana) from escape (vimutti).

Innocent devotees are either deliberately misled or misled by persons

misled themselves. So what is correct?

From the basic structure of intention (cetana) above, and the only

aim of the Buddha in teaching, it is evident that akusala/kusala are

properly translated ‚Äėunskilful/skilful‚Äô (as in Pali Text Society

translations). There can be now no misunderstanding of the role of

ethics in the Dhamma, as when there is no arising of action in the

arahat and nibbana is understood as the end of ethics.

In the famous parable, a man makes a raft with grass and reed to

cross to the other shore using his hands and feet. But he then does not

carry it on his shoulder. He leaves it behind and fares along. The

Dhamma is like that raft, to cross-over. The Buddha says: ‚ÄėMonks, when I

say this (ethical) Dhamma is to be abandoned, how much more so unethical

things?’

As mentioned, the ordinary householder is unable to extirpate the

fundamental conceit ‚ÄėI am‚Äô and with it all holdings (upadana) preventing

escape.

That is, while all intentions of the arhant are neither akusala/kusala,

all intentions of the householder are necessarily selfish - either

akusala kamma when killing or kusala kamma when imbued with intentions

of love, truthfulness, giving without expecting reward and so on.

With proper attention (yoniso manasikara) there is attenuation (yatodhi)

of the kilesa thus, from learning, understanding and practicing as

instructed. It is possible to shed the coarse obsession of the self (sakkaya)

and thereafter to be led onwards for extirpation of the resilient subtle

asmi mana in a future re-becoming, dependent on akusala/kusala already

done.

It is only in terms of unskilful and skilful that akusala/kusala

should be correctly understood by the householder.

Art of ancient Buddhist chant (Paritta)

Bhikkhu Saranapala

|

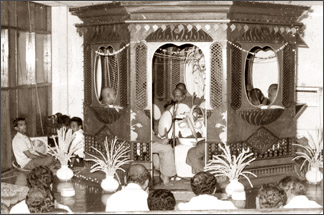

Monks chanting Pritht at a Pirith chanting ceremony. The Chant

itself is intended to inspire in both the chanter and the audience

total dispassion and detachment (anatta) and concentration. Usually

chanted in unison by an entire congregation of Buddhist monks in

‚Äúrecto tone‚ÄĚ, ancient Buddhist Chant creates an impressive

atmosphere of serenity and even grandeur.

|

The content of the Ancient Buddhist chant was invariably Buddha’s own

Teaching (Dharma), usually his own discourses to his disciples.

It is mentioned in the Buddhist literature that people from various

religious traditions sought benedictions from Sakyamuni Buddha, who

became known as a healer, at different times when people encountered

misfortunes and when they were scared of invisible evil forces.

For example, the royal family and the people of the Kingdom, when

stricken by menacing epidemics, sought protection and blessings from

Sakyamuni Buddha who later asked his personal attendant, Ananda, upon

the request from the royal family, to chant the Discourse on Jewels (Ratana

Sutta) by sprinkling water around the city of Visala.

The chant itself, devoid of any sensual stimuli, is intended to

inspire in both the chanter and the audience total dispassion and

detachment (anatta) and concentration. Usually chanted in unison by an

entire congregation of Buddhist monks in ‚Äúrecto tone‚ÄĚ, ancient Buddhist

Chant creates an impressive atmosphere of serenity and even grandeur.

While no such mystical union as in the care of the Gregorian chant

forms intended, its gear, earthly appeal renders one to be intensely

contemplative.

The Ancient Buddhist chant has been used for therapeutic purposes

since the time of the Buddha. It’s no small significance that early

Buddhist missionary monks sent to West by Indian Emperor, Asoka the

Great came to be known as therapeutics in the Greco-Roman world.

Among the many discourses, Buddhist chant derives from three

fundamental discourses, normally chosen by ancient Buddhist teachers, of

Sakyamuni Buddha, the Fully Awakened One.

These discourses, which contain the word of Sakyamuni Buddha, were

preserved in Pali, the ancient language the Buddha spoke. The Discourse

on Blessings, the Discourse on Jewels and the Discourse on Universal

Goodwill are the three key discourses. These are daily recited by

Buddhist monks and lay people alike for inspirational experience.

The Discourse on Blessings (Mangala Sutta from the Sutta Nipata)

contains thirty-six characteristic benedictions identified by the Buddha

himself as being most noble and propitious.

These benedictions, when recited with focused attention, advance

inner peace and serene joy. The Discourse on Jewels (Ratana Sutta,

another discourse from the Sutta Nipata) offers a remedial technique

through contemplation on spiritual riches bestowed by the Holy Triple

Gem - Buddha (Fully Awakened One), Dhamma (Doctrine) and Sangha (the

community of monks and nuns).

It is said that an ancient city stricken by three menacing epidemics,

evil spirits, diseases and famine was saved and continued to be

protected by the healing power of this discourse.

The Discourse on Universal Goodwill (Karaniya Metta Sutta, another

discourse chosen from the Sutta Nipata) contains a meditative theme on

universal love and compassion which during Sakyamuni Buddha’s own life

time came to the aid of a group of monks to continue to live in their

forest habitations unhindered by fear of evil spirits.

Building self-confidence and strength seem to be the primary

objective of this popular Discourse on Universal Goodwill At the end of

chanting of each discourse, the chanters, mainly the monks, perform an

act of truthfulness.

That is to say that the chanters use their spiritual powers to invoke

blessings by saying, ‚Äėby the power of the Holy Triple Gem may all

blessings be always upon you (the audience), may you enjoy good health

and may you live long.‚ÄĚ

According to the modern psychologists, human language and mind can

bring either evils or blessings to another human being. If the language

is wrongly used, this act could hurt the listeners where as if the

language is compassionately and rightly used, this act will definitely

bring blessings and healings to the listeners.

This is a scientifically experimented fact. Knowing the power of

wholesome language, Sakyamuni Buddha admonished the monks to do the

chanting with a compassionate mind and with pure awareness.

Following Sakyamuni Buddha’s advice, even today the Buddhist monks

perform the chanting out of great love and compassion with an undivided

attention. It is the teaching of Sakyamuni Buddha that a human mind,

replete of love, compassion, altruistic joy and equilibrium (four divine

virtues of Buddhist doctrine), can absolutely bring healings to others.

And also, a mind, replete of greed, anger, hatred, jealousy, pride

and self-centredness, would certainly bring miseries to oneself and

others alike.

Now, one may wonder as to why do Buddhists still listen to the

discourses that have been taught about two thousand five hundred years

ago by the Buddha. How could such words bring healings to others?

Sakyamuni Buddha, as a Fully Enlightened One, would never speak words

empty of meanings and benefits. The Enlightened One is always concerned

about sufferings of other beings and happiness of all living beings.

This is because of his infinitely great compassion and wisdom which

have been cultivated by eradicating all evils and cultivating spiritual

virtues. Sakyamuni Buddha, attaining the ultimate evolution of human

consciousness, became an embodiment of universal love and compassion.

He spoke with absolute purity of mind and hence, he brings

inner-transformation in the audience who is paying utter attention to

the words. It’s the inner-transformation that generates the spiritual

healing in the listeners. It is the belief that spiritual teachers

invariably use powerful and spiritually profitable words which became an

art of healing technique.

In order to reap the healing from the ancient Buddhist therapeutic

chant, the audience have to observe few steps. One must take a

comfortable sitting posture having the back straight so as to have a

balance between the mind and physicality.

In order to avoid all unnecessary distractions, the disconnection of

mind from the external world is recommended. It is imperative that the

listeners maintain the mind in the present moment to have an undivided

attention. Take a deep breath consciously so as to let the entire body

relax.

Conscious inhalation and exhalation are indispensable to become

natural within by following the breath all the way in and out. All

unwholesome thoughts and energies must be released along with exhalation

and all wholesome thoughts and energies must be developed along with

inhalation.

Finally, pay absolute attention to the melodious chant and keep on

inhaling and exhaling mindfully by feeling wholesome vibrations of the

chanting.

The following are benefits the audience may reap.

Stress-tension-Problem-free life, life of confidence free from fear, all

embracing Protection assurance, protection from unforeseen harm and

danger to one’s own self, good health, longevity, physical and mental

relaxation and calm, inner peace, serenity, healing physical &

psychological ai well-being are the immediate results that the audience

experience.

(The writer is a resident at the Westend Buddhist Centre Toronto,

Canada. He has a Pundit degree from Sri Lanka, M. A. from McMaster

University Hamilton and PhD from University of Toronto Canada).

Seeking solace in Buddhism

|

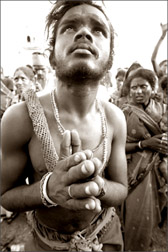

INDIA: Hindu dalits pray during a mass conversion to Buddhism

ceremony in Mumbai. AFP

|

Thousands of low-caste Hindus seeking to escape the oppression of

India’s rigid caste system embraced Buddhism in a mass conversion

recently.

Some 5,000 Dalits ‚ÄĒ those at the bottom of the ancient religious

hierarchy who were once known as untouchables ‚ÄĒ converted to Buddhism in

Mumbai, state capital of Maharashtra in western India, a Dalit group

said.

“We estimate that close to 5,000 Dalits have chosen the path towards

Buddhism by the end of the day,‚ÄĚ said Shravan Gaikwad, representative of

the Samatha Sainik Dal, a Dalit group.

Large-scale Dalit conversions take place periodically in India, with

close to 10,000 changing faith in October to mark the 50th anniversary

of the conversion of their deceased political leader Bhimrao Ramji

Ambedkar.

Ambedkar, a low-caste Hindu who rose to become a distinguished jurist

and played a key role in drafting India’s constitution, galvanised

Dalits with his public rejection of caste and Hinduism itself.

The conversion came just two weeks after a Dalit woman was sworn in

as chief minister of India’s largest state in an unexpected majority win

that some saw as a sign of how far the group has come.

But many Dalits say they still face severe discrimination and the

conversions are a way to make a fresh start, as well as to draw

attention to their plight.

Despite legislation banning caste discrimination, Dalits commonly

perform the most menial and degrading jobs in India. On occasion, they

are ostracised, beaten or even killed by members of upper-caste groups.

Sushil Kathe, who travelled thousands of kilometres to convert on

Sunday, remembers not being allowed to drink from the local well as a

child growing up in a village in a rice-growing district of the state.

“The upper caste came and did not allow us to drink water. They said

the place would be impure if we were allowed to take the water,‚ÄĚ said

Kathe, 25, who sells religious booklets.

|

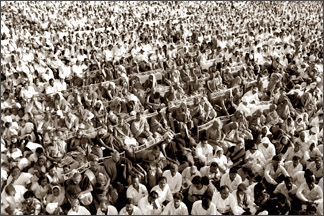

INDIA: Buddhist monks, draped with saffron robes, and Hindu dalits

sit during a mass conversion to Buddhism ceremony in Mumbai, 27 May

2007. AFP

|

The conversions have been opposed by right-wing Hindus who have

pushed some Indian states to legally restrict the practice, calling them

‚Äúforced.‚ÄĚ

But landless labourer D.G. Khade said conversion was his only hope of

a life of dignity in India.

“The Hindu religion is structured in such a way that we lower-caste

people will never get dignity,‚ÄĚ said Khade.

‚ÄúI am 45 and I don‚Äôt want my children to suffer my fate.‚ÄĚ

During the conversion, many of the Dalits wore blue caps to show

their brotherhood in their new religion, as they repeated the hymns

being chanted by Buddhist monks. Some also had their heads tonsured.

Low-caste Hindus constitute some 16 percent of India’s billion-plus

population and more than a fifth of Maharashtra’s population.

MUMBAI, AFP

|