|

Rabindranath Tagore:

Nation and the world

Reba Som

Rabindranath Tagore the first Asian to be awarded the Nobel Prize for

Literature in 1913, was born in 1861, three years after India came under

the British crown. In the history of India through time immemorial,

people of different races from across its borders have entered India in

waves. Each cultural encounter whether from Central Asian tribes or from

Muslim invaders, had left behind an indelible layer over an ancient

Hindu civilisation in the palimpsest fabric of India. In a song written

in 1910 Tagore celebrated the arrival of streams of people into India

through historical times – Aryans, non-Aryans, Dravidians, Chinese,

Shakas, Huns, Pathans, and Mughals. In waves they had come only to merge

into India’s sea of humanity.

|

|

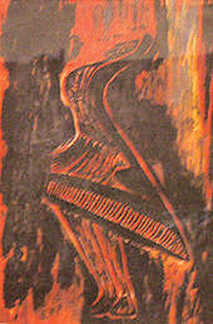

Tagore’s painting ‘Dancing Girl’,

undated ink-on-paper |

The arrival of the British, first as merchants and then as colonisers

was viewed very differently by Tagore. Unlike in the case of the

previous migrations he felt the British had come to India principally as

a commercial venture and there was little interest in merging with the

cultural ethos of India. He had of course in the same song that I

mentioned, written that to the west which had now opened its doors, his

message was – give and receive, meet and be met and do not return from

the shores of Bharat’s sea of humanity. However Tagore observed that

British imperialism came to India with its territorially-bounded model

of the western Nation-state, which sought to create a homogenised

entity.

To Tagore nations were “organisations of power – organisations for

production.” They were in essence monotonously the same – their

differences being merely differences in degrees of efficiency. However

people were living beings with distinct personalities finding self

expression in literature, art, social symbols and ceremonials. They

could not be regimented into one unit for production. Tagore’s free

spirit cried against such rigours of regimentation. He felt that India,

which was a ‘world in miniature’, had a ‘looseness in its diversity’ and

a ‘feebleness in its unity’, and could not be forced into the mould of a

Nation-state.

Tagore’s thoughts on the Nation crystallised as he lived through the

years of the national struggle for freedom. Although freedom came to

India in 1947 after the Poet had passed away in 1941, he had lived

through the long years of the anti-imperialist struggle and was able to

judge critically the concept of Nation brought by the British and found

it did not measure up to the ethos of a country like India.

It was remarkable that Tagore could make a fine distinction between

the Nation of the West, a straitjacketed British formula of Nation state

which he resisted and the Spirit of the West, with values of liberty and

equality which he welcomed. At a time when the idea of nationalism was

clubbed in the minds of ordinary people with the concepts of patriotism

and anti imperialism Tagore could dissociate his passionate opposition

to imperialism from the project of nationalism which he saw as being

alien to Indian tradition.

Tagore recognised that India had its fair share of racial problems

which it tried to deal through social regulation of differences as well

as spiritual recognition of unity. Although errors were constantly made

there was always an attempt to work out adjustments through experiments.

Tagore feared that the British formula of creating an administrative

unit with a uniform set of regulations and laws would regiment a diverse

people into an artificial entity. Tagore wrote: “In the west the

national machinery of commerce and politics turns out neatly compressed

bales of humanity which have their use and high market value but are

bound in iron hoops.”

Tagore made it clear that he had the highest regard for the British

as a people and treasured his interaction with outstanding intellectuals

and creative minds that he had met in the course of his visits to

Britain. But the British had come to India with narrow self interest

which made them manipulative and coercive without paying heed to the

spiritual core of India’s civilisational identity.

|

|

Tagore dabbled in primitivism: a

pastel-coloured rendition of a Malagan mask from northern

New Ireland |

Nor did Tagore ever discount the immense value of science in human

development which was introduced by the colonisers but he argued that

with the reasoning mind there must also be scope for the creative

imagination. Tagore was wary of the environmental degradation, popular

dislocation and dehumanising impact of mechanisation. In many of his

writings such as his celebrated play Rakta Karabi or the Red Oleanders

he speaks of the soul killing mechanised character of industrialisation

which can take away the simple joy of creativity in a people.

Tagore observed that the West could never understand the East as it

had not sent to her its humanity but only its machine. If the East had

to learn from the West it could not merely be the sum total of legal

codes and systems of civil and military services. The East and West had

to meet in the fullness of truth – the right hand wielding the sword had

need of the left which held the shield of safety.

Tagore’s views on the Nation were expressed in a series of lectures

delivered in Japan in 1916 and the United States in 1916-17. While

appreciating the artistic and aesthetic contributions of Japan, he did

not hesitate to critique militant Japanese imperialism against China in

his celebrated talk on Nationalism. Equally in his American tour that

followed, he launched on a sharp critique of the western state which he

felt was driven by the self-interest of a whole people which lacked

human and spiritual qualities – the lecture series, a major fund raiser

for Tagore’s university, was very successful but there was inescapable

irony in the fact that money had been earned in America while attacking

materialism.

Tagore’s main quarrel with the nationalism project was that he felt

that in the zeal to make money by exploitation of human and natural

resources the finer qualities of life – compassion, creativity and moral

and ethical values were being sacrificed. The strength of India he

repeatedly pointed out was in its spiritual tradition, where the wise

men of ancient times had reiterated the importance of keeping the focus

on the inner self. Tagore explained in his Sadhana lecture: “India put

all her emphasis on the harmony that exists between the individual and

the universal…the fundamental unity of creation was not simply a

philosophical speculation for India; it was her life-object to realise

this great harmony in feeling and in action. With meditation and

service, with a regulation of her life, she cultivated her consciousness

in such a way that everything had a spiritual meaning to her. The earth,

water and light, fruits and flowers were not merely physical phenomena

but necessary in the attainment of her idea of perfection. India was not

merely impelled by scientific curiosity or greed of material advantage

but with a larger feeling of joy and peace…This is not mere knowledge,

as science is, but it is a perception of the soul by the soul. This does

not lead us to power, as knowledge does, but it gives us joy.”

Tagore’s described his personal religion as the religion of Man. The

creativity of the human mind, its ability to face challenges and

transcend day to day obstacles to reach a state of equilibrium made man

God’s unique creation. The creative impulse in man made him the “dreamer

of dreams, the music-makers.”

Tagore believed that in each individual there was a consciousness of

the divine which was for him to discover and fathom. This god-within,

which he called jivan devata was in close communication with the larger

cosmic energy without. There was no hierarchy in this relationship but

mutual dependence. He elaborated by saying that the divinity in man and

the humanity in divinity together resulted in a creative unity which

made the universe pulsate with life.

Tagore sought to find this universal man in the world. He wrote: “I

do not put my faith in any new institution but in individuals all over

the world, who think clearly, feel nobly and act rightly, thus becoming

the channels of moral truth.”

|

|

Bauls in

Santiniketan during Holi |

In the days immediately preceding the First World War Tagore felt

that the west was going through a period of spiritual vacuum. It seemed

that there was a hand of destiny behind an overseas visit that took him

to England in 1912. The poem collection called Song-offerings or

Gitanjali that he brought with him to England on this visit was a

manuscript of translations of some of his own poems in Bengali, made

during a period of recuperation after an illness. These song/poems

seemed to soothe the minds of his international readers. He felt that as

a poet from the east he had been destined to carry to the west his poems

of cosmic beauty. This collection – Gitanjali – went on to win the Nobel

Prize for Literature in 1913.

Like Gandhi, Tagore was an ‘enlightened anarchist’, who believed in

the right of the individual to be the arbiter of his own destiny. The

strength of India lay in a loose universalism necessary because its

fabric was textured with many races and influences. Both Gandhi and

Tagore were reinforced in this belief from their respective overseas

experiences.

Gandhi’s South Africa experience – the satyagraha campaign in 1913-14

which knit Indians from multiple backgrounds into a mass movement

despite their vast differences was a universalism fashioned because of a

migration of peoples across the ocean, against all odds all in search of

livelihood – what Amitabha Ghosh calls in his Sea of Poppies the

solidarity of jahaj bhais.

Professor Sugata Bose speaks in his book A Hundred Horizons, about

the interplay of nationalism and universalism in the normative thought

and political practice among expatriates. The Gandhian satyagraha in

South Africa ended successfully because among the diaspora Indians there

was a “creative accommodation of differences rather than the imposition

of a singular uniformity”. Gandhi learnt much from his South Africa

experience and when he returned to India in 1914 he carried back the

conviction that instead of a narrow nationalism a loose universalism was

more efficacious.

Tagore too in the course of his sea voyages came to the realisation

that world culture flowed beyond the restricting barriers of nations. An

inveterate traveller he was fascinated to see how in south-east Asia

there had taken place the skilful interweaving of Indian and Islamic

cultural patterns on pre-existing local ones. He was fascinated to

discover pronounced Indian influences in the architecture, cuisine,

textiles and folklore in the region which had travelled over centuries

along the oceanic routes. In 1932 he exhorted people across the globe to

awaken from their post-modern slumber and weave together communities and

fragments into a larger and more generous pattern of human history.

Voice of Bengal

T B Ekanayaka - Culture and Arts Minister

In his native Bengal, Tagore was called the voice of Bengal, but he

is indeed a poet of the world. Tagore has touched millions of people

around the world with his novels, short stories, poetry, songs and

paintings. He was the only Indian to win the Nobel Prize for literature.

His contribution to art can stand the comparison with any art in

anywhere in the world. Tagore as a poet was mesmerized by mystery,

beauty and love of nature. It was his song, originally known as ‘Song of

Bengal’ later adopted as the Indian national anthem.

Santiniketan, which has shaped up the spiritual character of many of

the Sri Lankan outstanding personalities such as Professor E R

Sarachchandra, Ananda Samarakoon, Dr W D Amaradeva and Chitrasena,

established by Tagore, stands as a golden monument memorizing this great

artist and teacher.

Tagore visited Sri Lanka thrice. His last visit to Sri Lanka was in

1934 when he came with his troupe to stage some of his plays. It was

during this visit that he laid the foundation stone of Sri Palee College

at Horana, which was modeled on Santiniketan. Many Sri Lankan poets,

writers, dancers and painters were inspired by his works.

Rabindranath Tagore passed away on August 7, 1941. As Mahatma Gandhi

sadly noted, we, on that day lost not only the greatest poet of the age,

but an ardent nationalist who was also a humanitarian.

Programmes to commemorate Tagore anniversary

* Release of Commemorative Postal Stamp and First Day Cover by the

Government of Sri Lanka.

* Publication of a Volume on Tagore in English, Sinhala and Tamil

edited by Sandagomi

Coperahewa, University of Colombo.

* Rabindra Sangeet by Amar- Daya Foundation

* Essay competition in Sinhala, English and Tamil on Tagore for the

undergraduate students in the universities in Sri Lanka.

* A festival of feature films based on novels and stories of Tagore.

The Films include Agantuk, Pather Panchali, Charulatha, Ghare Baire and

Teen Kanya .

In September

* Exhibition of the digital copies of paintings of Tagore

* Photo exhibition on the life and travels of Tagore

In November

* Performance of Troupe from ICCR (Shaap Mochan). Shaap Mochan, the

play that enacted earlier in 1934 by Tagore in Sri Lanka, will be

performed by Manipuri Nartanalaya. Bimbavati Devi and her group of 21

artistes will be having performances in Sri Lanka.

* Visit of a five-member delegation from Sri Palee Campus and Sri

Palee college to Santiniketan

* Presentation of Books to Sri Palee Campus and Sri Palee College

The events are organized with the support of the Ministry of Posts,

Government of Sri Lanka, Ministry of Cultural Affairs and Arts,

Government of Sri Lanka, Universities of Colombo, Sri Jayawardenepura,

Kelaniya, High Commission of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, Tagore

Society of Sri Lanka, India Sri Lanka Foundation and Sarvodaya. |