Trojan Horse: Going back to the Greeks

Marina Warner

The way the Greek myths have been told has disguised the joins and

touched up the weirdness. Writers like Nathaniel Hawthorne in Tanglewood

Tales and Charles Kingsley in The Heroes, who enthralled me when I was a

child devouring the stories under the bedclothes by torchlight, patched

and pieced the myths into the coherent plots that we are familiar with.

Writers continue to work a ragbag of scraps into whole cloth,

disentangling the threads and recomposing the patterns. Very few readers

today go back to the sources, to handbooks like Apollodorus’ The

Library, or to the work of Quintus of Smyrna, who in the fourth century

wrote a sequel to the Iliad in 14 books.

When one does attempt to read these works, it’s often disappointing

to find how little their authors tried to shape the stories: some just

set down events like clerks in a court of law tallying ‘celestia crimina’,

heavenly crimes, as Ovid calls them.

|

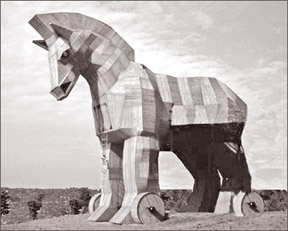

Trojan Horse |

When you look up the first known mention of this or that strand in a

myth, it’s hard to keep in mind that it might have been noted 700 years

before the next passage was set beside it to form a consistent plot.

Who remembers that Homer mentions only in passing the Judgment of

Paris, when Paris’ choice of Aphrodite over Hera and Athena sparked the

war in heaven that set in train the Trojan War? Or that the famous

episode when the Trojan Horse is smuggled into Troy does not take place

in the Iliad and isn’t fully dramatised in the Odyssey, but is known

chiefly from the Aeneid, written centuries later by a Roman with a

political agenda.

Homer could assume that his audience knew the outline of the myth of

Helen of Troy, and that in consequence he didn’t need to lay it all out.

But perhaps there never was a consistent and complete version of any

myth, one that you could walk all the way around and find that

everything matched and agreed from every angle.

In the 17th century, the grandest patrons like Cardinal Mazarin and

Cardinal Richelieu had their classical sculptures lavishly repaired,

with porphyry and gold additions to re-create a lost limb or a missing

nose.

This kind of mending is completely out of fashion now: restorers

prefer to make their own work distinguishable and even reversible so

that the original state can be recovered if wanted. But a desire for

authenticity hasn’t shaped the critical approach to the ruins of

stories, except in studies like this one, which pays out the multiple

strands in the myth of Helen of Troy.

Greek tragedy, Jean-Pierre Vernant wrote, presents its protagonists

as objects of debate, not examples of good conduct or even heroes

deserving of sympathy; the same can be said of characters in epic, like

Helen.

Laurie Maguire’s literary biography of Helen of Troy makes us face up

to moral ambiguities as it tracks the most beautiful woman in the world

across time and across media, from Homer to Hollywood, as her subtitle

has it.

Since historians can find no trace of the real Helen on a coin, a

stone or in a factual document, the search for her leads only to dreams

and fantasies. Bettany Hughes attempted an archaeological quest in her

Helen of Troy (2005), but was left wistfully hoping that Helen’s tomb

might be discovered one day.

Maguire finds traces of Helen of Troy everywhere, far beyond the

poems and plays in which she is a character, but an individual Helen

disappears, to emerge as the embodiment of a fundamental principle:

absolute beauty.

In Homer’s epics, in the Faust story taken up by Marlowe and in

Goethe’s long, eccentric poetic drama about the same legend, Helen of

Troy makes readers and audiences think about different issues: the good

of beauty, the reasons for war, eroticism and women’s sexuality,

responsibility and love.

Maguire considers what is meant by Helen’s beauty, what her history

was, how much she was to blame (was she abducted by Paris or did she go

willingly?), and what implications her story has for women at different

times.

Her book is packed with enthusiastic reading and looking, at

little-known classical material (Quintus of Smyrna) and at her own

academic specialism, Elizabethan literature (John Lyly gives Helen a

scar on her chin – the equivalent of the flaw in a Ming vase that

perfects it).

The book opens with the Iliad and closes with Derek Walcott’s

novel-like epic poem Omeros, in which Helen is a servant in the house of

Major and Mrs Plunkett, colonials in the Caribbean; this Helen wears a

yellow dress which she has either been given by her mistress or stolen

from her, a dress whose colour recalls the golden robes worn by the

divine Helen of Troy, woven for her by her mother, Leda. But such

continuities are only intermittent.

Maguire treats dozens of retellings: one mythographer has an immortal

Helen marry Achilles in the Underworld, while Thomas Heywood describes

her killing herself for her sad grey hairs.

Maguire has kept her survey within bounds by setting aside the

political uses of Helen of Troy, even though these flourished in the

Elizabethan period; she has also set aside the dramatic or performance

history, though she can’t resist the temptation to describe various

manifestations of Helen on stage and film, including the first stark

naked one (seen by the audience chastely from the back), by Maggie

Wright in an RSC production of Marlowe’s Dr Faustus.

Such economies are prudent, but the boundaries between

representations of Helen and of the politics of war keep collapsing, and

it’s a pity to ignore the sharp and timely elements in Helen’s story

that have inspired numerous recent dealings with the matter of Troy, as

in Tony Harrison’s Hecuba, when the chorus curses:

I pray as a small revenge

For all our dead and for Troy’s burning

Helen ends up as a refugee.

Ever since Mephistopheles summoned a devil to delude Faust into

believing that Helen of Troy stood before him and would make him

immortal with a kiss, there has been something fugitive about her; for

Maguire, her beauty, being absolute, cannot be grasped, and so leaves

desire famished, unappeased.

Helen of Troy comes to represent, not an ideal worth dying for, but a

gap in meaning, a vanishing. ‘This book, like the Trojan narratives that

it explores,’ Maguire writes, ‘is a study of absence, lack, gaps,

ambiguity, aporia, and the narrative impulse to completion and closure.’

In this respect, Maguire is setting herself against the synthesising

and reparatory impulses of recent fictional or poetic interpreters of

Greek myth: tellingly, she quotes another critic’s remark, that the

famous lines by Marlowe, usually declaimed in rapture, can be read as

inflected with irony and doubt: ‘Was this the face that launched a

thousand ships?’

One version of the myth that Maguire doesn’t mention nevertheless

illuminates her argument that Helen’s labile and phantasmic state shapes

our vision of her.

According to this version, Helen never sailed to Troy with Paris, but

was spirited away to Egypt, where she spent the war years as a priestess

of Artemis.

The Helen who went to Troy was an eidolon, which duped the Trojans

and the Greeks alike. They fought over an illusion. This strand of the

myth is very ancient: the poet Stesichorus, active in the sixth and

seventh centuries BC, suggested it after he was blinded by the gods for

defaming Helen.

He retracted his accusations in a palinode that is less a chivalrous

defence of Helen (and womankind) than a brilliant indictment of the

folly of war – and of men.

To be continued |