|

|

James R. Moore

Charg� d�affaires, a.i.

Embassy of the United States |

Message of Charg� d�affaires, a.i.

marking

the 233rd Independence Day of the

United States of America

Today marks the 233rd

anniversary celebrating the signing of America�s

Declaration of Independence. America�s Founding

Fathers knew that achieving independence would

require winning a difficult war that risked

bringing ruin on their fortunes, friends, and

families if they did not succeed. The Founding

Fathers� tremendous courage to fight for their

independence is not the most striking aspect of

the Declaration, however. It is, without a

doubt, their bold assertion that individual

rights must form the core of the society that

they were willing to risk so much to create.

The Declaration of

Independence demonstrates the primacy of

individual rights by stating that all men are

created equal and that they are endowed with

inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the

pursuit of happiness. The Founding Fathers use

these principles as the foundation of their

desired government, one that exists in order to

enable its citizens to secure their individual

rights. Because governments exist to serve their

citizens, the Declaration concludes that

governments should always be accountable to the

citizenry, deriving power entirely from their

consent.

It is with this sense of

individual rights and liberties that America

seeks to engage with other peoples around the

world today. The United States and Sri Lanka

have an extensive history of mutually beneficial

relations, beginning in 1789 when merchant ships

from New England docked in Sri Lanka�s harbors.

The first official American presence in

then-Ceylon began nearly 160 years ago in 1850

when John Black, an American merchant residing

in Sri Lanka, was named the American Commercial

Agent in Galle. Fifty years after Black�s

appointment, the American Commercial Agency

moved to Colombo and became a Consulate, which

paved the way for establishing an American

Embassy there shortly after Sri Lanka�s

independence in 1948.

Our strong partnership

continues today. In the past two years, the

United States has contributed over $60 million

for humanitarian assistance to Sri Lanka. The

funds have helped provide food, shelter, medical

supplies and other urgent needs to those

affected by the conflict. Moving forward, the

United States will continue to assist the

Government of Sri Lanka in its efforts to heal

the wounds of the 26-year conflict and to pave

the way for people to return to their homes as

soon as possible.

Our cooperation extends far

beyond government to government relations. Each

year, over 2500 Sri Lankans study in the United

States. At the same time, numerous Americans

come to Sri Lanka through programs such as

Fulbright and the American Institute of Sri

Lankan Studies to study Sri Lankan culture and

society. On the business front, the United

States remains Sri Lanka�s number one market for

exports, with almost $2 billion in goods in

2008. Likewise, Sri Lanka is a destination for

hundreds of millions of dollars of American

goods and services each year. U.S. goods

exports to Sri Lanka in 2008 were $283 million,

up 24.7 percent from 2007. In addition,

numerous American non-governmental organizations

are playing an important role in supporting the

Government�s efforts to build a lasting peace in

Sri Lanka.

Programs and partnerships like

these follow in the tradition of America�s

Founding Fathers by promoting a prosperous

global community that respects human rights and

dignity. With the recent election of a new

American President, the arrival later this

summer of a new American Ambassador to Sri

Lanka, and the dawn of peace in the country,

there is great opportunity to continue to expand

the positive relations between the American and

Sri Lankan people. On July 4, 1776, America�s

Founding Fathers announced the creation of a new

nation predicated on equality and respect for

all. We look forward to continuing that legacy

by building many more bridges of cooperation and

mutual understanding between the people of our

two countries in the years to come.

James R. Moore

Charg� d�affaires, a.i.

Embassy of the United States

|

|

Map of USA |

State Capitals and

Largest Cities

The following table lists the capital and largest city of

every state in the United States.

|

State |

Capital |

Largest city |

|

Alabama

|

Montgomery |

Birmingham |

|

Alaska

|

Juneau |

Anchorage |

|

Arizona

|

Phoenix |

Phoenix |

|

Arkansas

|

Little Rock |

Little Rock |

|

California

|

Sacramento |

Los Angeles |

|

Colorado

|

Denver |

Denver |

|

Connecticut

|

Hartford |

Bridgeport |

|

Delaware

|

Dover |

Wilmington |

|

Florida

|

Tallahassee |

Jacksonville |

|

Georgia

|

Atlanta |

Atlanta |

|

Hawaii

|

Honolulu |

Honolulu |

|

Idaho

|

Boise |

Boise |

|

Illinois

|

Springfield |

Chicago |

|

Indiana

|

Indianapolis |

Indianapolis |

|

Iowa |

Des Moines |

Des Moines |

|

Kansas

|

Topeka |

Wichita |

|

Kentucky

|

Frankfort |

Lexington |

|

Louisiana

|

Baton Rouge |

New Orleans |

|

Maine

|

Augusta |

Portland |

|

Maryland

|

Annapolis |

Baltimore |

|

Massachusetts

|

Boston |

Boston |

|

Michigan

|

Lansing |

Detroit |

|

Minnesota

|

St. Paul |

Minneapolis |

|

Mississippi

|

Jackson |

Jackson |

|

Missouri

|

Jefferson City |

Kansas City |

|

Montana

|

Helena |

Billings |

|

Nebraska

|

Lincoln |

Omaha |

|

Nevada

|

Carson City |

Las Vegas |

|

New Hampshire

|

Concord |

Manchester |

|

New Jersey

|

Trenton |

Newark |

|

New Mexico

|

Santa Fe |

Albuquerque |

|

New York

|

Albany |

New York City |

|

North Carolina

|

Raleigh |

Charlotte |

|

North Dakota

|

Bismarck |

Fargo |

|

Ohio |

Columbus |

Columbus |

|

Oklahoma

|

Oklahoma City |

Oklahoma City |

|

Oregon

|

Salem |

Portland |

|

Pennsylvania

|

Harrisburg |

Philadelphia |

|

Rhode Island

|

Providence |

Providence |

|

South Carolina

|

Columbia |

Columbia |

|

South Dakota

|

Pierre |

Sioux Falls |

|

Tennessee

|

Nashville |

Memphis |

|

Texas

|

Austin |

Houston |

|

Utah |

Salt Lake City |

Salt Lake City |

|

Vermont

|

Montpelier |

Burlington |

|

Virginia

|

Richmond |

Virginia Beach |

|

Washington

|

Olympia |

Seattle |

|

West Virginia

|

Charleston |

Charleston |

|

Wisconsin

|

Madison |

Milwaukee |

|

Wyoming

|

Cheyenne |

Cheyenne |

Source:

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000 figures. |

USA Facts and Figures

OFFICIAL NAME: United

States of America

CAPITAL CITY:

Washington, D.C.

TOTAL AREA: 9,826,630 sq km (3rd largest in the world, behind

Russia (1st) and Canada (2nd))

BIRTH RATE: 13.82

births/1,000 population

OVERALL LIFE EXPECTANCY:

78.11 years (75.65 years for men, 80.69 years for women)

POPULATION SIZE:

307,212,123 (3rd largest in the world, behind China (1st)

and India (2nd))

URBANIZATION: 82% of

total population

LITERACY RATE: 99% of

total population

RELIGIONS: Protestant

51.3%, Roman Catholic 23.9%, Mormon 1.7%, other Christian 1.6%, Jewish 1.7%,

Buddhist 0.7%, Muslim 0.6%, other or unspecified 2.5%, unaffiliated 12.1%, none

4% (2007 est.)

FLAG DESCRIPTION / SIGNIFICANCE: 13 equal

horizontal stripes of red (top and bottom) alternating with white; there is a

blue rectangle in the upper hoist-side corner bearing 50 small, white,

five-pointed stars arranged in nine offset horizontal rows of six stars (top and

bottom) alternating with rows of five stars; the 50 stars represent the 50

states, the 13 stripes represent the 13 original colonies; the design and colors

have been the basis for a number of other flags, including Chile, Liberia,

Malaysia, and Puerto Rico

US FEDERAL HOLIDAYS:

|

Thursday, January 1 |

New

Year�s Day |

|

Monday,

January 19 |

Birthday of Martin Luther King, Jr. |

|

Monday,

February 16* |

Washington�s Birthday |

|

Monday,

May 25 |

Memorial Day |

|

Friday,

July 3** |

Independence Day |

|

Monday,

September 7 |

Labor

Day |

|

Monday,

October 12 |

Columbus Day |

|

Wednesday, November 11 |

Veterans Day |

|

Thursday, November 26 |

Thanksgiving Day |

|

Friday,

December 25 |

Christmas Day |

|

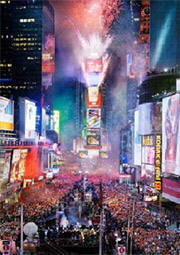

NEW YEAR�S DAY:

Like many countries around the world,

America celebrates the new year on January

1st, the first day on the American calendar.

Americans celebrate New Year�s eve, the

night leading into the first day of the new

year, in many different ways - the most

famous of which is the lowering of a large

illuminated ball on top of a skyscraper in

New York City�s Times Square. Although many

Americans celebrate New Year�s eve by

attending such displays, most Americans

spend the evening with family and friends,

usually at celebratory parties, and often

watch the public displays on television

instead. Both public and private New Year�s

eve celebrations last until midnight, when

the new year begins. Many adults celebrate

the beginning of the new year with a glass

of champagne, and couples often exchange a

kiss at the stroke of midnight. Many

championship, or �bowl,� games for

college-level American football take place

later on New Year�s Day, making it an

especially important occasion for sports

fans. Like many countries around the world,

America celebrates the new year on January

1st, the first day on the American calendar.

Americans celebrate New Year�s eve, the

night leading into the first day of the new

year, in many different ways - the most

famous of which is the lowering of a large

illuminated ball on top of a skyscraper in

New York City�s Times Square. Although many

Americans celebrate New Year�s eve by

attending such displays, most Americans

spend the evening with family and friends,

usually at celebratory parties, and often

watch the public displays on television

instead. Both public and private New Year�s

eve celebrations last until midnight, when

the new year begins. Many adults celebrate

the beginning of the new year with a glass

of champagne, and couples often exchange a

kiss at the stroke of midnight. Many

championship, or �bowl,� games for

college-level American football take place

later on New Year�s Day, making it an

especially important occasion for sports

fans. |

|

|

Martin Luther King Day:

Martin Luther King, Jr. Day marks the

birthday of the Reverend Doctor Martin

Luther King, Jr. It is observed on the third

Monday of January each year, which always

falls close to Dr. King's actual birthday of

January 15. It is one of three United States

federal holidays to commemorate an

individual person. In the 1950�s and 1960�s,

Dr. King was the chief spokesman of the

nonviolent civil rights movement, which

successfully opposed racial discrimination

in American federal and state laws. Although

he was assassinated in 1968, Dr. King�s

legacy continues to have a strong impact on

American politics and social life today. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day marks the

birthday of the Reverend Doctor Martin

Luther King, Jr. It is observed on the third

Monday of January each year, which always

falls close to Dr. King's actual birthday of

January 15. It is one of three United States

federal holidays to commemorate an

individual person. In the 1950�s and 1960�s,

Dr. King was the chief spokesman of the

nonviolent civil rights movement, which

successfully opposed racial discrimination

in American federal and state laws. Although

he was assassinated in 1968, Dr. King�s

legacy continues to have a strong impact on

American politics and social life today. |

|

|

|

WASHINGTON�S BIRTHDAY:

Washington's Birthday is celebrated

on the third Monday of February. It is also

commonly known as Presidents Day. Although

schools and businesses previously were

closed during the holiday, its proximity to

Abraham Lincoln�s birthday, another holiday,

led the Federal Government to honor both

presidents on the same day. When Martin

Luther King, Jr. Day was created as an

additional day off of work, many employers

stopped closing shop on Presidents� Day to

compensate for the new day off. Because many

businesses now stay open during Washington�s

Birthday, it has lost much of its luster in

recent years. Today, Washington�s Birthday

is most familiar to Americans as an occasion

for special sales at retail outlets,

particularly car dealerships. Washington's Birthday is celebrated

on the third Monday of February. It is also

commonly known as Presidents Day. Although

schools and businesses previously were

closed during the holiday, its proximity to

Abraham Lincoln�s birthday, another holiday,

led the Federal Government to honor both

presidents on the same day. When Martin

Luther King, Jr. Day was created as an

additional day off of work, many employers

stopped closing shop on Presidents� Day to

compensate for the new day off. Because many

businesses now stay open during Washington�s

Birthday, it has lost much of its luster in

recent years. Today, Washington�s Birthday

is most familiar to Americans as an occasion

for special sales at retail outlets,

particularly car dealerships. |

|

|

MEMORIAL DAY:

Memorial Day is a national holiday

that is observed on the last Monday of May.

It commemorates U.S. men and women who died

while serving in the military. Although the

holiday was first enacted to honor veterans

of the American Civil War, it was expanded

after World War I to honor American

casualties from any war or military action.

Because the holiday falls on a Monday, many

American families take advantage of the

extended weekend to travel. Additionally,

many Americans also hold �Memorial Day

Barbeques,� outdoor cookouts where they

gather with friends and family to enjoy

grilled hamburgers, hot dogs, and other

snacks. Memorial Day is a national holiday

that is observed on the last Monday of May.

It commemorates U.S. men and women who died

while serving in the military. Although the

holiday was first enacted to honor veterans

of the American Civil War, it was expanded

after World War I to honor American

casualties from any war or military action.

Because the holiday falls on a Monday, many

American families take advantage of the

extended weekend to travel. Additionally,

many Americans also hold �Memorial Day

Barbeques,� outdoor cookouts where they

gather with friends and family to enjoy

grilled hamburgers, hot dogs, and other

snacks. |

|

|

INDEPENDENCE DAY:

American Independence Day is

celebrated every year on July 4th. Commonly

referred to as the Fourth of July, it

commemorates the signing of the Declaration

of Independence in 1776. The Declaration

officially severed ties between the United

States and the British Monarchy, and is the

formal beginning of the American Revolution.

A little known fact about the holiday is

that the Declaration of Independence was

actually signed on July 2, but the public

did not know that it had been signed until

two days later, at which point until the

Declaration had been edited into its final

form and was widely distributed. Americans

commemorate the Fourth of July with outdoor

picnics and barbeques, and sit down to enjoy

elaborate fireworks displays at night. American Independence Day is

celebrated every year on July 4th. Commonly

referred to as the Fourth of July, it

commemorates the signing of the Declaration

of Independence in 1776. The Declaration

officially severed ties between the United

States and the British Monarchy, and is the

formal beginning of the American Revolution.

A little known fact about the holiday is

that the Declaration of Independence was

actually signed on July 2, but the public

did not know that it had been signed until

two days later, at which point until the

Declaration had been edited into its final

form and was widely distributed. Americans

commemorate the Fourth of July with outdoor

picnics and barbeques, and sit down to enjoy

elaborate fireworks displays at night. |

|

|

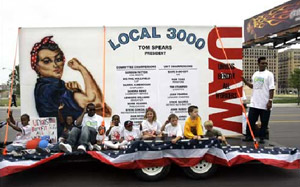

LABOR DAY:

Labor Day is observed every year on

the first Monday in September. The holiday

originated in 1882 as the Central Labor

Union of New York City sought to create "a

day off for the working citizens," and the

American Congress declared it a federal

holiday on 1894. Traditionally, Labor Day is

celebrated by most Americans as the symbolic

end of the summer. Today, Labor Day is often

regarded as a day of rest and parades, and

an occasion for picnics, barbecues, water

sports, and a last chance for travel before

the end of summer. Labor Day marks the

beginning of the American football season at

both the professional and university level. Labor Day is observed every year on

the first Monday in September. The holiday

originated in 1882 as the Central Labor

Union of New York City sought to create "a

day off for the working citizens," and the

American Congress declared it a federal

holiday on 1894. Traditionally, Labor Day is

celebrated by most Americans as the symbolic

end of the summer. Today, Labor Day is often

regarded as a day of rest and parades, and

an occasion for picnics, barbecues, water

sports, and a last chance for travel before

the end of summer. Labor Day marks the

beginning of the American football season at

both the professional and university level. |

|

|

COLUMBUS DAY:

Columbus Day commemorates Christopher

Columbus�s discovery of America, and is

celebrated on the second Monday in October.

Many schools and businesses around the

country close in recognition of the holiday,

although many choose to stay open as well.

Schools often have special lesson plans in

the days leading up to the holiday that

teach students about Columbus�s voyage and

the importance of his arrival in the New

World. Many members of the Italian-American

community consider the holiday a celebration

of their heritage. Columbus Day commemorates Christopher

Columbus�s discovery of America, and is

celebrated on the second Monday in October.

Many schools and businesses around the

country close in recognition of the holiday,

although many choose to stay open as well.

Schools often have special lesson plans in

the days leading up to the holiday that

teach students about Columbus�s voyage and

the importance of his arrival in the New

World. Many members of the Italian-American

community consider the holiday a celebration

of their heritage. |

|

|

VETERANS DAY:

Veterans Day is an annual American

holiday honoring military veterans, and is

celebrated on November 11. If November 11th

falls on a weekend during a particular year,

then the nearest weekday is designated for

holiday leave. It was originally called

Armistice Day, marking the anniversary of

the signing of the Armistice that ended

World War I. In 1954 the name of the holiday

was officially changed to Veterans Day, in

order to recognize the sacrifices of

American soldiers in subsequent military

conflicts. Veterans Day is marked with

parades and ceremonies to honor American

servicemen and women around the country. Veterans Day is an annual American

holiday honoring military veterans, and is

celebrated on November 11. If November 11th

falls on a weekend during a particular year,

then the nearest weekday is designated for

holiday leave. It was originally called

Armistice Day, marking the anniversary of

the signing of the Armistice that ended

World War I. In 1954 the name of the holiday

was officially changed to Veterans Day, in

order to recognize the sacrifices of

American soldiers in subsequent military

conflicts. Veterans Day is marked with

parades and ceremonies to honor American

servicemen and women around the country. |

|

|

THANKSGIVING DAY:

Thanksgiving Day is celebrated on the

fourth Thursday in November. Although it was

historically a religious observation to give

thanks to God, it is now considered a

secular holiday. Thanksgiving commemorates

early English settlers� success and

gratitude after surviving an especially

brutal first winter in America. Most

Americans celebrate by gathering at home

with family or friends for a holiday feast.

The feast reflects the food eaten by

American colonists, traditionally featuring

dishes like mashed potatoes with gravy,

sweet potatoes, cranberry sauce, sweet corn,

other fall vegetables, and pumpkin pie. A

full turkey (often baked or fried) serves as

the meal�s centerpiece, and has become so

symbolically linked with the holiday that

Thanksgiving is often referred to as �Turkey

Day.� Although the Thanksgiving feast may

appear to be an unnecessary indulgence,

Thanksgiving is also an occasion for

community service. Many Americans help to

feed the needy at Thanksgiving time, and

most communities have annual food drives

that collect packaged and canned foods for

this purpose. Thanksgiving Day is celebrated on the

fourth Thursday in November. Although it was

historically a religious observation to give

thanks to God, it is now considered a

secular holiday. Thanksgiving commemorates

early English settlers� success and

gratitude after surviving an especially

brutal first winter in America. Most

Americans celebrate by gathering at home

with family or friends for a holiday feast.

The feast reflects the food eaten by

American colonists, traditionally featuring

dishes like mashed potatoes with gravy,

sweet potatoes, cranberry sauce, sweet corn,

other fall vegetables, and pumpkin pie. A

full turkey (often baked or fried) serves as

the meal�s centerpiece, and has become so

symbolically linked with the holiday that

Thanksgiving is often referred to as �Turkey

Day.� Although the Thanksgiving feast may

appear to be an unnecessary indulgence,

Thanksgiving is also an occasion for

community service. Many Americans help to

feed the needy at Thanksgiving time, and

most communities have annual food drives

that collect packaged and canned foods for

this purpose. |

|

|

CHRISTMAS DAY:

Like in many countries around the

world, Christmas Day is a cause for

celebration in the United States. Celebrated

on December 25th, Christmas gives Americans

of all religions time away from work and

school that they can spend with friends and

family. Although many Christian Americans

commemorate the holiday by exchanging

presents, many Americans of other faiths

engage in holiday gift giving as well.

Although the holiday has a strong religious

foundation that is a key part of many

Americans� Christmas experience, for other

Americans the holiday�s festivities take on

a more secular role of setting the mood at

the beginning of the winter season. Many

neighborhoods and public areas are

illuminated with strings of lights to give a

festive mood, with many of these displays

installed shortly after Thanksgiving. Some

of the more famous Christmas displays

include an enormous Christmas tree in

Rockefeller Center in New York City, and

Washington D.C.�s impressive National

Christmas Tree that is displayed across the

street from the White House. Like in many countries around the

world, Christmas Day is a cause for

celebration in the United States. Celebrated

on December 25th, Christmas gives Americans

of all religions time away from work and

school that they can spend with friends and

family. Although many Christian Americans

commemorate the holiday by exchanging

presents, many Americans of other faiths

engage in holiday gift giving as well.

Although the holiday has a strong religious

foundation that is a key part of many

Americans� Christmas experience, for other

Americans the holiday�s festivities take on

a more secular role of setting the mood at

the beginning of the winter season. Many

neighborhoods and public areas are

illuminated with strings of lights to give a

festive mood, with many of these displays

installed shortly after Thanksgiving. Some

of the more famous Christmas displays

include an enormous Christmas tree in

Rockefeller Center in New York City, and

Washington D.C.�s impressive National

Christmas Tree that is displayed across the

street from the White House. |

|

|

Other

celebrations in US:

HALLOWEEN:

Halloween is a non-Federal holiday

celebrated on October 31. The day is often

associated with the colors orange and black,

and is strongly associated with symbols such

as the jack-o'-lantern, a hollowed-out

pumpkin whose sides are carved to create

small openings that become illuminated when

a lit candle is placed inside it. Halloween

activities include bonfires, costume

parties, visiting seasonal attractions,

carving jack-o'-lanterns, reading scary

stories, and watching horror movies. Perhaps

the most notable Halloween activity,

however, is called �trick-or-treating.�

Trick-or-treating in America began in the

early 1900�s when youths would knock on

people�s doors on Halloween night and

threaten to cause mischief unless the

residents bribed them with food. In the last

fifty years, however, trick-or-treating has

become a much more wholesome endeavor.

Instead of mischievous youths, young

children dressed in

costumes

knock on neighbors� doors, threatening no

harm and instead saying �trick or treat� as

a polite way to ask for some pieces of

candy. Halloween is a non-Federal holiday

celebrated on October 31. The day is often

associated with the colors orange and black,

and is strongly associated with symbols such

as the jack-o'-lantern, a hollowed-out

pumpkin whose sides are carved to create

small openings that become illuminated when

a lit candle is placed inside it. Halloween

activities include bonfires, costume

parties, visiting seasonal attractions,

carving jack-o'-lanterns, reading scary

stories, and watching horror movies. Perhaps

the most notable Halloween activity,

however, is called �trick-or-treating.�

Trick-or-treating in America began in the

early 1900�s when youths would knock on

people�s doors on Halloween night and

threaten to cause mischief unless the

residents bribed them with food. In the last

fifty years, however, trick-or-treating has

become a much more wholesome endeavor.

Instead of mischievous youths, young

children dressed in

costumes

knock on neighbors� doors, threatening no

harm and instead saying �trick or treat� as

a polite way to ask for some pieces of

candy. |

|

|

VALENTINE�S DAY:

Americans celebrate Valentine�s Day

on February 14th. Although Valentine�s Day

is not a Federal Holiday, it is nonetheless

an important holiday for many Americans. The

day is most closely associated with the

mutual exchange of love notes in the form of

"valentines". Valentine�s Day symbols

include the heart-shaped outlines, doves,

and images of the winged Cupid. Since the

19th century, handwritten notes have largely

given way to mass-produced greeting cards.

Many couples use the holiday as an occasion

to go out to a nice dinner, and most

exchange small presents. These gifts

typically include roses and chocolates

packed in a red satin, heart-shaped box. In

the 1980s, the diamond industry began to

promote Valentine's Day as an occasion for

giving jewelry. In some North American

elementary schools, children decorate

classrooms, exchange cards, and eat sweets

to celebrate the holiday. In the greeting

cards, these students often mention what

they appreciate about each other. The rise

of Internet popularity is creating new

traditions. Every year millions of people

use digital means of creating and sending

Valentine's Day greeting messages such as

e-cards, or printable greeting cards. Americans celebrate Valentine�s Day

on February 14th. Although Valentine�s Day

is not a Federal Holiday, it is nonetheless

an important holiday for many Americans. The

day is most closely associated with the

mutual exchange of love notes in the form of

"valentines". Valentine�s Day symbols

include the heart-shaped outlines, doves,

and images of the winged Cupid. Since the

19th century, handwritten notes have largely

given way to mass-produced greeting cards.

Many couples use the holiday as an occasion

to go out to a nice dinner, and most

exchange small presents. These gifts

typically include roses and chocolates

packed in a red satin, heart-shaped box. In

the 1980s, the diamond industry began to

promote Valentine's Day as an occasion for

giving jewelry. In some North American

elementary schools, children decorate

classrooms, exchange cards, and eat sweets

to celebrate the holiday. In the greeting

cards, these students often mention what

they appreciate about each other. The rise

of Internet popularity is creating new

traditions. Every year millions of people

use digital means of creating and sending

Valentine's Day greeting messages such as

e-cards, or printable greeting cards. |

|

|

Built in America

Golden Gate Bridge, San Francisco,

California.

An international icon of American

engineering genius, the Golden Gate Bridge

opened in 1937 and remains one of the

longest suspension bridges in the world. The

main span of 4,200 feet crosses the

turbulent waters at the entrance to San

Francisco Bay. Chief engineer Joseph B.

Strauss started the construction project in

1933. An international icon of American

engineering genius, the Golden Gate Bridge

opened in 1937 and remains one of the

longest suspension bridges in the world. The

main span of 4,200 feet crosses the

turbulent waters at the entrance to San

Francisco Bay. Chief engineer Joseph B.

Strauss started the construction project in

1933.

|

|

|

The Statue of Liberty

The

Statue of Liberty (French: Statue de la

Libert�), officially titled Liberty

Enlightening the World (French: La libert�

�clairant le monde), is a monument that was

presented by the people of France to the

United States of America in 1886 to

celebrate its centennial. Standing on

Liberty Island in New York Harbor, it

welcomes visitors, immigrants, and returning

Americans traveling by ship. The

Statue of Liberty (French: Statue de la

Libert�), officially titled Liberty

Enlightening the World (French: La libert�

�clairant le monde), is a monument that was

presented by the people of France to the

United States of America in 1886 to

celebrate its centennial. Standing on

Liberty Island in New York Harbor, it

welcomes visitors, immigrants, and returning

Americans traveling by ship.

The copper-clad statue,

dedicated on October 28, 1886, commemorates

the centennial of the signing of the United

States Declaration of Independence and was

given to the United States by France to

represent the friendship between the two

countries established during the American

Revolution. Fr�d�ric Auguste Bartholdi

sculpted the statue and obtained a U.S.

patent for its structure. Maurice Koechlin�chief

engineer of Gustave Eiffel's engineering

company and designer of the Eiffel

Tower�engineered the internal structure.

Eug�ne Viollet-le-Duc was responsible for

the choice of copper in the statue's

construction and adoption of the repouss�

technique, where a malleable metal is

hammered on the reverse side.

The statue is of a robed woman holding a

torch, and is made of a sheeting of pure

copper, hung on a framework of steel

(originally puddled iron) with the exception

of the flame of the torch, which is coated

in gold leaf (originally made of copper and

later altered to hold glass panes). It

stands atop a rectangular stonework pedestal

with a foundation in the shape of an

irregular eleven-pointed star. The statue is

151 ft (46 m) tall, but with the pedestal

and foundation, it is 305 ft (93 m) tall.

Worldwide, the Statue of Liberty is one of

the most recognizable icons of the United

States[10] and was, from 1886 until the jet

age, often one of the first glimpses of the

United States for millions of immigrants

after ocean voyages from Europe. Visually,

the Statue of Liberty appears to draw

inspiration from il Sancarlone or the

Colossus of Rhodes.

The statue is the central part of Statue of

Liberty National Monument, administered by

the National Park Service. |

|

|

AMERICAN HISTORY ON A PLATE

By Andrew Weisberg

From

the signing of the Declaration of

Independence through the present day, few

aspects of American life can be said to

reflect the American experience as much as

American foods. Over their country�s

history, Americans have gone from worrying

about having enough food to eat to deciding

which foods they should choose to eat in

order to have a healthier and longer life.

While the broad category of what can be

considered �American food� encompasses

dishes, tastes, and cooking styles from

around the world, it is clear that the

evolution is indicative of America�s larger

journey as a nation.

At the time of American

independence, most Americans lived in rural

areas and food staples varied by region.

Most of these early Americans relied on the

land for both food and economic livelihood.

Americans living on the Atlantic coast

relied on fish, whales, and crabs, and many

of these states are still renowned for their

seafood. Although early Americans made good

use of their country�s expansive coastline,

they reaped even greater benefits from its

rich soil. Most early Americans were

farmers, and even famous American leaders

like George Washington owned large farming

plantations. Farmers in early America grew

cash crops like tobacco and cotton as well

as food crops like wheat, barley, rice, and

corn. Most American farms at the time were

self-sufficient, growing multiple crops and

raising different types of livestock on the

same piece of land. Early American farmers

ate what they grew, turning wheat into

flower for bread and pies, or mixing it with

cornmeal to make cornbread and an

oatmeal-like snack called �corn mush.� Meat

was often roasted, salted, or smoked, and

came from livestock raised on the farm or

animals like deer, rabbits, and turkeys that

were hunted in the wild.

This type of diet was

prevalent in America until after the Civil

War. The industrial revolution of the late

1800�s brought a rapid increase in urban

jobs, which in turn brought waves of

immigrants, as well as migrants from rural

America, to the cities. As more and more

people moved to America�s cities, food

demand increased although the number of

farmers supplying it diminished. This

imbalance, as well as the increased distance

between Americans and where their food was

produced, necessitated revolutions in

farming methods that dramatically increased

per-acre crop yields, as well as advances in

canning technology and ever-increasing

railroad networks that made food easier to

preserve and transport. Technology�s

relationship to American food progressed

from one of handling food to new methods of

creating the food itself after the Second

World War. Americans embraced many of these

new products, and items like instant coffee,

which had originally been created for use by

Allied troops serving overseas, became

ingrained in mainstream American life during

the post-war years.

The immigrants arriving on

both of America�s coasts before and after

World War Two brought with them new tastes,

recipes, and ideas that have since become

firmly established in American culture.

Chinese immigrants brought their cuisine to

America�s West Coast, although in its

present version American Chinese food

features sweeter, tangier tastes and

includes much more meat than traditional

Chinese food does in order to appeal to

American preferences. Dishes now considered

some of the most iconic American foods

today, moreover, came from European

immigrants to America�s East Coast, who

introduced their fellow Americans to the

pizza, the hamburger, and of course the

frankfurter � better known as the hot dog.

Although many of America�s

iconic foods are variations on dishes

originally introduced from abroad, some

American favorites are completely original.

A sandwich called the Philadelphia cheese

steak is one such example. In its simplest

form, a Philadelphia cheese steak consists

of thinly sliced pieces of beef steak and

melted cheese that are placed along the

inside of a long sandwich roll. The cheese

steak was created during the 1930s in the

Italian immigrant section of Philadelphia,

in a hot hog stand run by two brothers,

Harry and Pat Olivieri. Tired of eating hot

dogs, one day the two brothers sliced up

some beef and grilled it with some onions.

The brothers piled the meat on rolls and

were about to dig in when a cab driver

arrived for lunch, smelled the meat and

onions cooking and demanded one of the

sandwiches. The sandwich soon became

immensely popular, and the two brothers

eventually opened up a restaurant to sell

it. 20 years later, an improvising employee

at the Oliveris� restaurant was the first to

add cheese to the sandwich, and the

combination became an overnight sensation.

As the United States has

become even more culturally diverse in

recent years, American palates have expanded

to accommodate new dishes and styles as well

as old favorites. Mexican dishes, especially

tacos and burritos (meat, beans, rice, and

vegetables wrapped in a flour pancake) are

increasingly popular today, as is

Spanish-style tapas dining, where a group of

people orders a variety of appetizer dishes

for all to share instead of each person

ordering a main dish. Japanese sushi is

another growing trend, and is generally

viewed as a stylish and trendy food choice.

Perhaps the most important

recent trend in American eating habits

relates to Americans� growing desire for

knowledge about the food that they eat.

Increased access to information over the

internet, as well as new laws mandating the

publication of food products� ingredients

and nutritional value, have led many

Americans to seek out foods that are

healthier, organic, and often locally

produced. Many supermarkets have begun

carrying organic foods in response to this

demand, and one nationwide supermarket chain

was launched in order to cater exclusively

to it. Because this movement is relatively

recent, however, it is difficult to tell

whether or not the organic food movement is

a momentous shift in American dietary habits

or just a passing trend.

America�s food has evolved

throughout its history, drawing inspiration

from other cultures while at the same time

contributing some of its own unique

creations. American food, like America

itself, has been shaped by historical events

and technological revolutions since its

founding. America�s existence not only as a

melting pot of culinary styles, but as a

melting pot of ideas, is what gives American

food, and the country itself, its enduring

strength.

|

|

|

Globalization and the U.S.

Financial System

By Charles R. Geisst

Globalization helped fuel the

current financial crisis, and it will

undoubtedly be employed to help resolve it.

Charles R. Geisst is a

professor of finance at Manhattan College.

His many books include

Wall Street: A History,

and he is the editor of the Encyclopedia

of American Business History.

In the decades following

World War II, the idea of globalization

became more and more popular when describing

the future of the world economy. Some day,

markets for all sorts of goods and services

would become integrated and the benefits

would be clear. The standard of living would

be raised everywhere as barriers to trade,

production, and capital fell. The goal was

noteworthy and has been partially realized.

But recently it hit a major bump in the

road.

Globalization has many

connotations. Originally, it meant

international ease of access. Barriers to

trade and investment eventually would

disappear, and the international flow of

goods and services would increase. Free

trade and common markets were created to

facilitate the idea. A world without

barriers would help distribute wealth more

evenly from the wealthy to the poor.

To date, only financial

services have succeeded in becoming truly

global. Fast-moving financial markets, aided

by speed-of-light technology, have swept

away national boundaries in many cases,

making international investing effortless.

Government restrictions have been removed in

most of the major financial centers, and

foreigners have been encouraged to invest.

This has opened a wide panorama of

investment possibilities.

This phenomenon is not new.

Since World War II, many governments have

loosened restrictions on their currencies,

and today the foreign exchange market is the

world�s largest, most liquid financial

market, trading around the clock. And there

is no distinction made in it because of

those national peculiarities or restrictions

for the major currencies. If governments

allow their currencies to trade freely, as

most in developed countries, then a dollar

or a euro can trade in Hong Kong or Tokyo as

easily as it does in Dubai or New York.

Cross-Border Trading

Other financial markets

quickly followed this precedent. The

government bond markets, corporate bond

markets, and the equities markets all

started to develop links based on new and

faster technology. Forty years ago, Gordon

Moore, one of the founders of software giant

Intel, made his famous prediction (Moore�s

Law) that microchip capacity would double

every two years. New, faster chips were able

to accommodate an increasing number of

financial transactions, and before long that

capacity spawned even more transactions.

Soon, traders were able to cross markets and

national boundaries with an ease that made

the supporters of globalization in other

sections of the economy jealous. During the

same time period, manufacturers had been

promoting the idea of the universal car,

without the same level of success.

Wall Street and the other

major financial centers prospered. Customers

were able to obtain executions for their

stock trades with a speed unimaginable in

the mid-1990s. The NYSE (New York Stock

Exchange) and the NASDAQ (National

Association of Securities Dealers Automated

Quotations) abandoned their old method of

quoting stock prices in fractions and

adopted the decimal system. Computers did

not like fractions, nor did the old method

encourage trading at the speed of light.

Customers were now able to trade via

computer in many major markets as quickly as

in their own home markets. True cross-border

trading was born, making financial services

the envy of other industries that long had

dreamed of globalization.

The results were astonishing.

Volume on the NYSE increased from a record 2

billion shares in 2001 to a record 8 billion

in 2008. Volume on the foreign exchange

markets was in the trillion-dollar

equivalents on a daily basis. The various

bond markets were issuing more than a

trillion worth of new issues annually rather

than the billions recorded in previous

record years. The value of mergers and

acquisitions equally ran into the trillions

annually. The volumes and the appetite for

transactions appeared endless.

A Traditional Cycle

The U.S. economy

traditionally had witnessed long periods of

prosperity before slowing down

substantially, usually brought to a

temporary halt by an asset bubble that

finally ran out of hot air. The situation

had been replayed many times since 1793,

when the first major economic downturn was

recorded in New York. Similar problems were

recorded at least eight times until 1929.

Each boom was followed by a bust, some more

severe than others. The post-1929 depression

finally ushered in far-reaching reforms of

the banking system and securities markets.

Until 1929, these recessions

were called �panics�. The term �depression�

was used once or twice in the early 20th

century, but during the 1930s the term

became associated exclusively with that

decade. The traditional cycle is still in

evidence. The recession of 2001 followed the

dot-com bust, and many of the day traders

who had employed the new computer technology

retreated to the sidelines much as their

forebears had done in the 19th century. A

recession followed, temporarily slowing down

the appetite for speculative gains.

The 19th and the 21st

centuries had more in common than might have

been imagined. After gaining its

independence from Britain, the United States

had been dependent on foreign capital for

the first 120 years of its existence. Until

World War I, much of the American

infrastructure and industry had been

financed with foreign money, mostly in the

form of bonds. Americans produced most of

the goods and services they needed, but

capital was always in short supply until the

war changed the face of geopolitics.

The situation remained

unchanged until the late 1970s, when the

position again was reversed. The U.S.

household savings ratio declined and foreign

capital poured into the country. Bonds were

the favorite again, but the equities markets

also benefitted substantially. Consumers,

accounting for about two-thirds of the U.S.

gross domestic product since the 1920s,

bought domestic and foreign goods, while

foreigners supplied the capital necessary to

finance the federal government and many

American industries. The situation persists

today, with about half the outstanding U.S.

Treasury bonds in the hands of the Chinese

government alone.

The Mortgage Boom

After the dot-com bust and

the Enron and WorldCom scandals, it appeared

that Wall Street was due to take a breather

for lack of new ideas to fuel another

bubble. But it was a combination of cyclical

trends that reappeared and together fueled

the greatest short-term boom yet.

Globalization, an influx of foreign capital,

and esoteric financial analytics combined

with residential housing to produce the most

explosive � and potentially destructive �

boom/bust cycle ever witnessed in American

history.

The recent market bubble was

created by the boom in residential housing.

Normally, housing follows stock market booms

but has not caused them. In the wake of the

dot-com bust and the post-September 11

trauma, the situation became reversed. The

home became the center of many investors�

attention. First-time buyers abounded, and

many others clamored to refinance their

existing mortgages. The new thing was really

an older thing dressed up by modern finance.

This phenomenon was difficult

to detect in its early stages. All of the

factors that converged to produce it had

been seen before. Many were well-known and

time-proven methods in finance.

Securitization had been used for several

decades by the U.S.-related housing finance

agencies to convert pools of residential

mortgages into securities that were

purchased by investors. This provided even

more available funds for the housing market

at a time that demand was very high after

2001. The new thing on Wall Street became

financing the �American Dream� � the idea

that everyone should own his or her own

home.

Demand for the securitized

bonds proved strong, so strong that Wall

Street securities houses began cranking them

out at increasingly fast speed. Much of the

demand came from foreign investors � central

banks, banks, sovereign wealth funds, and

insurance companies � all drawn by their

attractive yields. Dollars were being

recycled by these investors, especially

central banks and the sovereign wealth

funds, from the current account balances

they were accumulating with the United

States. The money left the United States as

Americans purchased imports from foreign

producers and found its way back as

investments.

Victims of Their Own Success

The mortgage boom began after

2001, and within a couple of years it was in

full stride. Demand remained strong for

mortgage-backed securities, and soon

subprime mortgages, credit default swaps,

and other exotic collateral based on

derivatives became part of the asset

backing. By the late summer of 2007, as

short-term interest rates rose from

historically low levels, cracks began to

appear in this collateral and asset values

began to collapse, creating the banking and

insurance crises within months. In the past,

without the technology, the results would

have taken years.

The boom was aided

immeasurably by the deregulation of the U.S.

financial markets in 1999, officially

culminating over two decades of a gradual

easing of once stringent rules. The new

financial environment it created allowed

banks and investment banks to cohabit,

something that had not been allowed since

1933. When they began to share the benefits

of deregulation under the same roof, older

ideas of risk management began to crumble in

a greater quest for profit.

The credit market and

collateral crisis marks the end of the

almost 40-year legacy of the federally

related housing agencies and all of the

benefits they provided since the social

legislation passed during the 1960s. Wall

Street, the credit markets, and the U.S.

housing industry all were victims of their

own success when the markets collapsed in

2008. Greed, lack of regulatory oversight,

and the sophistication of structured

finance, which created many of these exotic

financial instruments, all played a role in

the most recent setback for the markets and

the economy as a whole.

Most importantly, the crisis

demonstrates the pitfalls of deregulation

and globalization. Unfortunately, the

appropriate skepticism that must accompany

every boom has been missing. Globalization

helped fuel the crisis and will undoubtedly

be employed to help resolve it. Deregulation

will be swept aside in favor of more

stringent institutional controls on

financial institutions designed to prevent

fraud and deceit. It took almost four years

after the market crash of 1929 to erect a

regulatory structure to separate different

types of banks and establish national

securities laws. Moore�s Law suggests that

it will occur faster this time around. The

forces that shaped globalization will demand

it. |

|

|

U.S. Energy Efficiency

Advances in 2009

A summary of efficiency

initiatives in the American Recovery and

Reinvestment Act of 2009.

The

economic stimulus law enacted in February

2009 recognizes the close ties between the

economy and energy production, and provides

a variety of funding sources and incentives

to increase efficiency and encourage broader

adoption of renewable energy technologies.

In announcing his budget plan

for the forthcoming year, President Obama

also emphasized his commitment to greater

investments in renewable technologies. �We

will invest $15 billion a year to develop

technologies like wind power and solar

power; advanced biofuels, clean coal, and

more fuel-efficient cars and trucks built

right here in America,� the president said

in his February 24 speech to Congress.

Highlighted below are

selected new measures targeting efficiency

initiatives.

� $5 billion for the

Weatherization Assistance Program. This

30-year-old program pays for improvements to

the homes of low-income families to increase

energy efficiency. More than 5.6 million

low-income families have received these

services since the program began in 1976.

The program increases the comfort of these

homes and lowers families� energy bills for

the long-term.

� $4 billion for energy

efficiency retrofits in public housing units

maintained by the Department of Housing and

Urban Development.

� $300 million for rebates

paid to consumers who purchase

energy-efficient appliances.

� $3.2 billion in grants to

states and local governments to support

energy efficiency and conservation projects

in government buildings.

� $4.2 billion to the U.S.

General Services Administration to convert

federal buildings into high-performance

green buildings, combining increased

efficiency techniques and renewable energy

production.

� $6.9 billion to the

Federal Transit Administration for

distribution to local public transit

agencies� investments in conservation and

expansion of mass transit options.

� $50 million for efforts

to increase the energy efficiency of

information and communication technologies.

� Increased tax credits for

homeowners and businesses that make

efficiency improvements to their own

properties. |

|

|

A Musical Tour of America

A tour of U.S. musical

shrines in every region of the country

There are dozens of ways to

organize a visit to the United States�you

can tour its major cities, hike the national

parks, or sightsee the famous monuments. In

this essay, Dr. John Hasse suggests a more

unique way: explore America by touring its

many and varied musical shrines which can be

found in every region of the country.

Even people who have

never visited the United States are familiar

with its music. During its nearly 230 years

as a nation, this country has developed an

enormous amount of original music that is

astonishing in its variety, vitality,

creativity, and artistic accomplishment.

Running the gamut from the humblest banjo

tunes and down-home dances to the haunting

blues of Robert Johnson and the brilliant

jazz cadenzas of Charlie Parker, American

music is one of the most important

contributions the United States has made to

world culture.

Arguably, no nation in

history has created such a wealth of vibrant

and influential musical styles as has the

United States. American music reflects the

energy, diversity, spirit, and creativity of

its people. You don't have to understand

English to feel the power of Aretha

Franklin, the plaintiveness of Hank

Williams, the joie de vivre of Louis

Armstrong, the directness of Johnny Cash,

the virtuosity of Ella Fitzgerald, or the

energy of Elvis Presley.

These musicians and their

musical genres are available to people

around the world via recordings, downloads,

Internet radio, Voice of America broadcasts,

and television and video. But to really

appreciate and understand them, there is

nothing like visiting the places where they

were born, and where their musical creations

evolved and are preserved.

This article offers visitors

a unique tour of the United States by

surveying music museums and shrines across

the country. Other musical traditions

brought here by more recent immigrants�such

as salsa and mariachi�and other new U.S.

styles, including grunge, rap, and hip-hop,

have yet to be associated with dedicated

museums or historical landmarks. They are,

though, easy to find in nightclubs and

festivals, or by searching the World Wide

Web. Nightclubs come and go at a dizzying

pace, and new festivals pop up all the time,

so the emphasis here is on those locations

that are likely to be around in the years

ahead.

Jazz.

Jazz is the most consequential, influential,

and innovative music to emerge from the

United States, and New Orleans, Louisiana is

widely known as the birthplace of jazz. No

city, except perhaps for New York City, has

received more visiting jazz aficionados than

New Orleans. In the wake of the devastating

blow to the "Crescent City" by Hurricane

Katrina on August 29, 2005, unfortunately,

international jazz enthusiasts may need to

remain alert to news reports concerning the

rebuilding of New Orleans.

New Orleans residents and

jazz devotees worldwide eagerly await the

reopening of the French Quarter and

Preservation Hall [http://www.preservationhall.com],

a bare-bones pair of wooden rooms that has

served since 1961 as a shrine of sorts to

the traditional New Orleans sound. Other New

Orleans treasures that will be revived

include the Louisiana State Museum's

exhibition on jazz [http://lsm.crt.state.la.us/site/],

complete with the musical instruments of

Louis Armstrong, Bix Beiderbecke and other

early jazz masters, and the New Orleans Jazz

National Historical Park Visitor Center

[http://www.nps.gov/jazz], which will once

again offer self-guided walking tours and

other information from its North Peters

Street location.

In the 1920s and 1930s,

Kansas City, Missouri was a hotbed of

jazz�Count Basie, Charlie Parker, Mary Lou

Williams, and other greats performed there.

You can get a sense of the music by visiting

the old jazz district around 18th and Vine

Streets, where you'll find the American Jazz

Museum [http://www.americanjazzmuseum.com]

and the historic Gem Theater.

In New York City, jazz from

all periods can be heard in the city's many

historic nightclubs, including the Village

Vanguard [http://www.villagevanguard.net/frames.htm],

the Blue Note [http://www.bluenote.net], and

Birdland [http://www.birdlandjazz.com].

Harlem's Apollo Theater [http://www.apollotheater.com]

has seen many great jazz artists, as has

Carnegie Hall [http://www.carnegiehall.org]

located at 57th Street and 7th Avenue. The

city's newest jazz shrine is Jazz at Lincoln

Center [http://www.jazzatlincolncenter.org],

a $130-million facility, opened in October

2004, featuring a 1,200-seat concert hall,

another 400-seat hall with breathtaking

views overlooking Central Park, and a

140-seat nightclub, Dizzy's Club Coca-Cola.

In the Queens borough of New

York City stands the home of, to my mind,

the most influential U.S. jazz musician,

Louis "Satchmo" Armstrong (1901-71). The

Louis Armstrong House [http://www.satchmo.net]

offers tours and a small gift shop.

Ragtime.

This syncopated, quintessentially piano

music is one of the roots of jazz. A small

display of artifacts from Scott Joplin, "The

King of Ragtime Writers," is at the State

Fair Community College in Sedalia,

Missouri�the town where Joplin composed his

famous Maple Leaf Rag. Sedalia hosts the

annual Scott Joplin Ragtime Festival. In

much larger St. Louis, you can visit one of

Joplin's homes, the Scott Joplin House State

Historic Site [http://www.mostateparks.com/scottjoplin.htm].

Blues.

The twelve-bar blues is arguably the only

musical form created wholly in the United

States; and the state of Mississippi is

often considered the birthplace of the

blues. Certainly the state produced many

leading blues musicians, including Charley

Patton, Robert Johnson, Howlin' Wolf, Muddy

Waters, and B.B. King. Most came out of the

broad floodplain known as the Mississippi

Delta, which runs 200 miles along the

Mississippi River from Memphis, Tennessee

south to Vicksburg, Mississippi. This part

of Mississippi boasts three modest blues

museums: the Delta Blues Museum [http://www.deltabluesmuseum.org]

in Clarksdale, the Blues & Legends Hall of

Fame Museum [http://www.bluesmuseum.org] in

Robinsonville, and the Highway 61 Blues

Museum located

[http://www.highway61blues.com] in Leland.

Highway 61 is a kind of blues

highway, the road traveled by blues

musicians heading north to Memphis,

Tennessee. In Memphis, there is a statue of

W.C. Handy, composer of "St. Louis Blues"

and "Memphis Blues," on famed Beale Street

[http://www.bealestreet.com] as well as a

B.B. King's Blues Club [http://www.bbkingclubs.com].

Bluegrass Music.

Bluegrass music�syncopated string-band music

from the rural hills and "hollers" (hollows

or valleys) of the eastern U.S. Appalachian

mountain range�has found a growing audience

among city-dwellers. You can visit the

International Bluegrass Music Museum

[http://www.bluegrass-museum.org] in

Owensboro, Kentucky and the smaller Bill

Monroe's Bluegrass Hall of Fame [http://www.beanblossom.com]

in Bean Blossom, Indiana. A newly-designated

driving route, the Crooked Road: Virginia's

Music Heritage Trail [http://www.thecrookedroad.org],

is a 250-mile route in scenic southwestern

Virginia that connects such sites as the

Ralph Stanley Museum, the Carter Family

Fold, the Blue Ridge Music Center, and the

Birthplace of Country Music Museum.

Country Music.

Long the epicenter of country music,

Nashville, Tennessee boasts the Grand Ole

Opry [http://www.opry.com], home of the

world's longest-running live radio

broadcast, with performances highlighting

the diversity of country music every Friday

and Saturday night, and the impressive

Country Music Hall of Fame [http://www.countrymusichalloffame.com].

Its permanent exhibit, Sing Me Back Home: A

Journey Through Country Music, draws from a

rich collection of costumes, memorabilia,

instruments, photographs, manuscripts, and

other objects to tell the story of country

music.

Nearby are Historic RCA

Studio B, where Elvis Presley, Chet Atkins,

and other stars recorded, and Hatch Show

Print, one of the oldest letterpress print

shops in America whose posters have featured

many of country music's top performers. In

Nashville, you can also see Ryman Auditorium

[http://www.ryman.com], former home to the

Grand Ole Opry, as well as many night spots,

such as the Bluebird Caf� [http://www.bluebirdcafe.com],

one of the nation's leading venues for

up-and-coming songwriters. In Meridian,

Mississippi, the Jimmie Rogers Museum

[http://www.jimmierodgers.com] pays tribute

to one of country music's founding figures.

Rock, Rhythm & Blues, and

Soul.

Rock 'n' roll music shook up the nation and

the world, and more than 50 years after

emerging, it continues to fascinate and

animate hundreds of millions of listeners

around the globe. Memphis, Tennessee, is

home to Elvis Presley's kitschy but

interesting home known as Graceland [http://www.elvis.com],

the Sun Studio [http://www.sunstudio.com]

where Elvis made his first recordings (and

many other famous musicians have

subsequently recorded), the Stax Museum of

American Soul [http://www.staxmuseum.com]

which covers Stax, Hi, and Atlantic Records,

and the Memphis and Muscle Shoals sounds.

The Memphis Rock and Soul

Museum features a superb Smithsonian

exhibition tying together the story of

Memphis from the 1920s to the 1980s with

blues, rock, and soul�from W. C. Handy

through Elvis and Booker T. and the MGs

[http://www.memphisrocknsoul.org].

Detroit, Michigan offers the

Motown Historical Museum [http://www.motownmuseum.com]

with memorabilia from the Supremes,

Temptations, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye,

Aretha Franklin and other soul singers who

recorded for Motown Records.

If you're a big Buddy Holly

fan, you might trek to the Buddy Holly

Center [http://www.buddyhollycenter.org] in

Lubbock, Texas.

The formidable Rock 'n' Roll

Hall of Fame [http://www.rockhall.com] in

Cleveland, Ohio fills a stunning building

designed by renowned architect I.M. Pei with

hundreds of rock and roll artifacts and

audio-visual samples. In Seattle,

Washington, The Experience Music Project in

the Frank Gehry-designed building [http://www.emplive.org]

is a unique, interactive museum, which

focuses on popular music and rock.

Folk Music.

Most nations have their own indigenous

music�in Europe and the United States it is

often categorized as "folk music." Folk

music is passed along from one person to the

next via oral or aural tradition, i.e., it

is taught by ear rather than through written

music. Typically the origin of the songs and

instrumentals is shrouded in mystery and

many different variants (or versions) of

each piece exist, honed through the ears,

voices, fingers, and sensibilities of many

different performers. The easiest way to

find live folk music is at one of the many

folk music festivals held throughout the

United States. The biggest is the annual

Smithsonian Folklife Festival [http://www.folklife.si.edu]

held every June and July on the National

Mall in Washington, D.C. The 40th annual

festival will be held in 2006.

Latino Music.

Of course, the United States is a "New

World" country of immigrants and each new

ethnic group that arrives brings its own

musical traditions which, in turn, continue

to inevitably change and evolve as they take

root in their non-native soil. Hispanics now

account for the largest minority group in

the United States, and they practice many

musical traditions.

Played by ensembles of

trumpet, violin, guitar, vihuela, and

guitarr�n, Mexican mariachi music can be

heard in many venues in the American

Southwest; the closest thing to a mariachi

shrine is La Fonda de Los Camperos, a

restaurant at 2501 Wilshire Boulevard in Los

Angeles, which in 1969 pioneered in creating

mariachi dinner theater.

Bandleader-violinist Nati Cano has been

honored with the U.S. government's highest

award in folk and traditional arts, and his

idea of mariachi dinner theater has spread

to Tucson, Arizona; Santa Fe, New Mexico;

San Antonio, Texas; and other cities.

The vibrant dance music

called salsa, which was brought to New York

City by Cuban and Puerto Rican �migr�s, can

be heard and danced to in nightclubs of New

York, Miami and other cosmopolitan cities. A

museum exhibition called �Az�car! The Life

and Music of Celia Cruz, featuring the Queen

of Salsa who spent the majority of her

career in the United States, has been

mounted at the Smithsonian Institution's

National Museum of American History in

Washington, D.C. It will be on display

through October 31, 2005. An on-line

exhibition may viewed at http://www.americanhistory.si.edu/celiacruz/.

Cajun Music.

The Prairie Acadian Cultural Center in

Eunice, Louisiana (about a three-hour drive

west of New Orleans) tells the story of the

Acadian, or Cajun, peoples �who emigrated

here after being evicted from Canada in the

1750s�and their distinctive Francophone

music and culture [http://www.nps.gov/jela/pphtml/facilities.html].

The nearby Liberty Theater is

home to a two-hour live radio program,

Rendez-vous des Cajuns, featuring Cajun and

zydeco bands, single musical acts, and Cajun

humorists every Saturday night. Eunice is

also home to the Cajun Music Hall of Fame

[http://www.cajunfrenchmusic.org], and the

Louisiana State University at Eunice

maintains a web site devoted to contemporary

Creole, zydeco, and Cajun musicians [http://www.nps.gov/jela/Prairieacadianculturalcenter.htm].

Show Tunes and Classical

Music.

No tour of music in the United States would

be complete without mentioning two other

great offerings: show tunes and classical

music. Although the latter originated in

Europe, native composers such as Aaron

Copland and Leonard Bernstein brought an

exuberant American style to the classical

genre. The Lincoln Center [http://www.lincolncenter.org/index2.asp]

and historic Carnegie Hall in New York City

[http://www.carnegiehall.org/jsps/intro.jsp]

are the best-known venues for classical

offerings, although excellent performances

by some symphony orchestras can be found

throughout the country [http://www.findaconcert.com/]

For show tunes enthusiasts,

Broadway is America's shrine to live

theater. Broadway is the name of one of New

York City's most famous streets. It also

refers to the entire 12-block area around

it, known as "The Great White Way" of

theater lights. In the United States,

revivals of Broadway musicals appear

throughout the year at regional theaters.

Musical Instruments.

New York City's Metropolitan Museum of Art

[http://www.metmuseum.org/Works_of_Art/department.asp?dep=18]

exhibits rare musical instruments as works

of art. The Smithsonian's National Museum of

American History in Washington, D.C.

displays rare decorated Stradivarius

stringed instruments, pianos, harpsichords,

and guitars, and has, as well, exhibits

devoted to jazz legends Ella Fitzgerald and

Duke Ellington.

In Carlsbad, California�not

far from San Diego �the Museum of Making

Music [http://www.museumofmakingmusic.org]

displays over 500 instruments and

interactive audio and video samples. The

Fender Museum of Music and Arts [http://www.fendermuseum.com]

in the Los Angeles suburb of Corona,

California has an exhibition on 50 years of

Fender guitar history.

In the Great Plains town of

Vermillion, South Dakota, the National Music

Museum [http://www.usd.edu/smm] displays 750

musical instruments.

No matter where you go in the

United States, you'll find Americans in love

with "their" music�be it jazz, blues,

country-western, rock and roll, or any of

its other myriad forms�and happy to share it

with visitors. It's a fun and informative

way to tour every region of the U.S.A.

RECOMMENDED READING

Bird, Christiane. The Da Capo

Jazz and Blues Lover's Guide to the U.S. 3rd

Ed. New York: Da Capo Press, 2001.

Cheseborough, Steve. Blues

Traveling: The Holy Sites of Delta Blues.

2nd Ed. Jackson: University Press of

Mississippi, 2004.

Clynes, Tom. Music Festivals

from Bach to Blues: A Traveler's Guide.

Canton, MI: Visible Ink Press, 1996.

Dollar, Steve. Jazz Guide:

New York City. New York: The Little

Bookroom, 2003.

Fussell, Fred C. Blue Ridge

Music Trails. Chapel Hill and London:

University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

Knight, Richard. The Blues

Highway: New Orleans to Chicago: A Travel

and Music Guide. Hindhead, Surrey, UK: