|

‘The emotion of art is impersonal’:

The process of depersonalization

We ended last time's discussion of Eliot's Objective Correlative

theory by looking at it in the light of Shakespeare's definition of

Imagination's role in the creative process. This, interestingly, was

even more of an ‘obiter dictum’ than Eliot's, being thrown up in the

course of the dramatic action of a play. The remarkableness of

Shakespeare's insight, and foresight, is aptly described by Owen

Barfield in ‘History in English Words': We ended last time's discussion of Eliot's Objective Correlative

theory by looking at it in the light of Shakespeare's definition of

Imagination's role in the creative process. This, interestingly, was

even more of an ‘obiter dictum’ than Eliot's, being thrown up in the

course of the dramatic action of a play. The remarkableness of

Shakespeare's insight, and foresight, is aptly described by Owen

Barfield in ‘History in English Words':

“In such a passage we seem to behold him standing up, a figure of

colossal stature, gazing at us over the heads of the intervening

generations. He transcends the flights of time and the laborious

building up of meanings and, picking up a part of the outlook of an age

which is to succeed his by nearly two hundred years, gives it momentary

expression before he lets it drop again.

That mystical conception which the word embodies in these lines—a

conception which would make imagination the interpreter and part creator

of a whole unseen world—is not found again until the Romantic Movement

has begun.”

Famous definitions

It is strange that Eliot's own theory makes no mention of Imagination

even though the Romantic Movement and Coleridge's famous definition

preceded his by over a hundred years. In fact, as noted last time,

Eliot's version makes the creative process look rather like a scientific

one. Indeed, it is reminiscent of another of his pronouncements which he

actually explains in scientific terms. This is found in his most famous

essay, ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent'. Speaking of the ‘process

of depersonalization’ whereby ‘art may be said to approach the condition

of science’, he invites us to consider the role of the catalyst in

chemistry and draws this analogy:

|

|

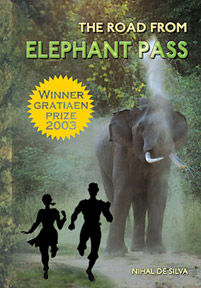

Nihal de

Silva |

“When the two gases (oxygen and sulphur dioxide) are mixed in the

presence of a filament of platinum, they form sulphuric acid. This

combination takes place only if the platinum is present; nevertheless

the newly formed acid contains no trace of platinum, and the platinum

itself is apparently unaffected: it has remained inert, neutral, and

unchanged. “When the two gases (oxygen and sulphur dioxide) are mixed in the

presence of a filament of platinum, they form sulphuric acid. This

combination takes place only if the platinum is present; nevertheless

the newly formed acid contains no trace of platinum, and the platinum

itself is apparently unaffected: it has remained inert, neutral, and

unchanged.

The mind of the poet is the shred of platinum. It may partly or

exclusively operate upon the experience of the man himself; but, the

more perfect the artist, the more completely separate in him will be the

man who suffers and the mind which creates; the more perfectly will the

mind digest and transmute the passions which are its material.”

Eliot goes on to speak of ‘significant emotion’, namely the ‘emotion

which has its life in the poem and not in the history of the poet. The

emotion of art’, he concludes, ‘is impersonal.’ The resulting concept of

the impersonality of true poetry has, needless to say, been tediously

overworked.

It hardly, for instance, holds good in the face of Shakespeare's

sonnets, most of Wordsworth's poetry and Eliot's own ‘Four Quartets'.

These surely represent the intensely personal experiences of the poets

themselves as presented directly to us. The notion of impersonality

seems quite inappropriate here. Yet, we cannot afford to throw out the

baby with the bath-water.

Substitute the word ‘detachment’ for impersonality, and the

desirability of there being a measure of detachment between the artist

and his work of art will be readily acknowledged. And if truth be told

such detachment is even to be found in the aforementioned works.

In these poems Wordsworth and Eliot are each, undoubtedly, ‘a man

speaking to men’ in accordance with the former's idea of what a poet

should be. Shakespeare, too, is obviously speaking to us as well as

addressing the objects of his devotion.

Yet all three achieve that necessary degree of detachment through the

imaginative use of situation and imagery. In the Sonnets the experience

of unrequited devotion becomes the occasion for profound thoughts about

life and death, time and permanence, love and lust, which absorb us more

than the actual experience of ‘the man who suffers'.

And while ‘Tintern Abbey’ is all about Wordsworth's deepening

awareness of nature's influence, nature itself becomes for us as well as

for him ‘a presence that disturbs'; it is through his evocation of that

presence rather than through his ‘elevated thoughts’ that we share the

‘joy’ of them, that indefinable ‘sense sublime.’

As for ‘Waste Land’, Eliot's profound meditations on time past,

present and future are distanced from himself by their association with

the locations that provide the titles of the four quartets, ‘Burnt

Norton’ etc., and by the myriad ancillary images these engender, eg. the

rose garden, the river etc.

Greater credence

Thus, even if you cannot talk about impersonality here the existence

of an ‘art emotion’ is undeniable. And when we range further afield the

idea of impersonality itself gains greater credence. What is personal,

for instance, about Keats ‘Ode to Autumn’, Wallace Stevens’ ‘Anecdote of

the Jar’ and Alfreda de Silva's ‘Stone Girl in an Indian Garden'? They

seem pretty impersonal for all that they are moving or

thought-provoking. And it is here that the theory of the objective

correlative makes its presence felt.

It is seen to be bound up with the process of depersonalization and

the production of the art emotion. Autumn becomes a symbol of the idea

that ‘change is the mother of beauty'. The jar seems to embody, inter

alia, the restrictive effects of the civilizing process and the

philosophizing tendency. The retold legend of the stone girl is a

frightening revelation of man's latent animalism. And when you look back

you see that the objectivity of these poems has been achieved through a

superb choice of correlatives for the subjective realities they

represent.

But we must remember that Eliot spoke of the objective correlative in

writing about a play, Shakespeare's ‘Hamlet'. And it is in the realms of

drama and fiction that the concept takes on an even greater relevance.

As we have discussed earlier a novel is not effective unless it has the

feel, gives the illusion, of real life. For this purpose its social

context, its characters and their relationships and its story or plot

are essential. So are these essential for drama, though here context

becomes less important and plot more so.

And it is these indispensable ingredients of fiction and drama that

provide the ‘set of objects, situations and chains of events’ that

function as objective correlatives to the subjective issues under

consideration.

When these correlatives are imaginatively conceived the experience of

the play or the novel moves into a dimension of impersonality; and

thence into one of universality. The artist has succeeded in embodying

his ideas and passions in his plot and characters, thereby transmuting

them into something rich and strange.

Thus Emily Bronte's yearning for romantic love and her adoration of

the earth are convincingly incorporated in the person of Cathy. And what

happens to the latter in the story shows her understanding of the

consequences of indulging these passions to an extreme.

It is the experience of Cathy, not of the author, that captures our

imagination, and this is because of the chain of events and the

situations in which Cathy moves and suffers. And in ‘The Road from

Elephant Pass’ Nihal de Silva's choice of the civil war as his context

and a credible escape story arising therefrom as his plot is what

enables him to objectify his hatred of prejudice and his longing for

brotherhood among the races.

‘Elephant Pass’ has been dismissed by some as an adventure story for

schoolboys. This is because they have failed to realise that the literal

adventure is the objective correlative of the greater adventure of the

development of a loving relationship between two deadly enemies: and

that the way this relationship develops is itself the objective

correlative of how, through mutual knowledge and understanding, the

rapprochement that is desired on a universal scale might be achieved.

For such critics ‘a hawk’ in Pound's words, ‘is a hawk'. But their

misjudgment too is a vindication of Eliot's theory!

Personal friendships

Turning to drama, Shakespeare finds in the events preceding and

following the assassination of Julius Caesar an objective correlative

for his thoughts about the difficulty of reconciling personal friendship

and commitment to the general good when the two loyalties came into

conflict; also the trauma that ensues when the high-minded soul is

persuaded to adopt questionable means to achieve an ideal. ‘Julius

Caesar’ is often linked with ‘Hamlet’ for its depiction of a hesitant

hero, Brutus, and for its profusion of compelling speeches. Our

reference to it, therefore, is is an appropriate prelude to our taking

up for consideration Eliot's contention that ‘Hamlet’ is an artistic

failure.

|