Nari Kunjar an unusual art form

Sirimavo Ediriweera

This article looks at a quaint, if not quirky genre of art that has

had its origins in Medieval India. The earliest samples known are

assigned the 17th century A.D. This particular art form is identified by

the name, Kunjar, a Sanskrit word, which means, The Elephant. This is

largely due to the place of prominence attributed to the Elephant form

in its early designs.

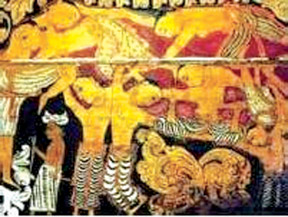

The Kunjar art form was also practised in Sri Lanka, samples of which

were found in Buddhist Temple Art of the 17th and 18th centuries A.D.

This superb painting of the model of Kunjar is from the temple murals of

the Dalada Maligawa, Kandy. It can also be taken as a useful guide to

support the view that the predominant feature of this art form is the

creation of ‘composites’, honing on the artist’s ability to manipulate a

composite design. The Kunjar art form was also practised in Sri Lanka, samples of which

were found in Buddhist Temple Art of the 17th and 18th centuries A.D.

This superb painting of the model of Kunjar is from the temple murals of

the Dalada Maligawa, Kandy. It can also be taken as a useful guide to

support the view that the predominant feature of this art form is the

creation of ‘composites’, honing on the artist’s ability to manipulate a

composite design.

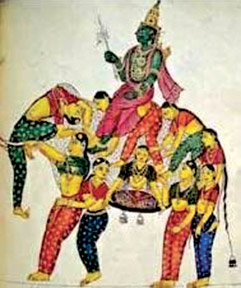

It is indeed an unusual form of art in that it is primarily designed

to highlight the artist’s skills of composition and ‘assemblage’, most

importantly within the parameters of a frame work. Animal frames were

commonly used though initially restricted, to those of the Elephant and

the Horse. As regards the use of inanimate frames, these appear also to

be restricted to that of the palanquin, pandal and ratha or chariot.

The most impressive aspect of this art form was the innovative use of

the figure of the woman, nari, presented usually in multiple numbers.

There were however limits to these as determined the artistic

excellence, or the lack of it of a particular composition. The

presentation of women, are most often carried out with a certain

artistic flair. Taking into consideration even the few samples produced

here, one can only but surmise that the male artists, as this art genre

was largely their domain, would have had a field day when it came to

depicting the figure of the female form. More so as no guide lines were

offered, the merits of each individual art work depended on how cleverly

the women were artistically presented and assembled within a given frame

work.

Often these women are portrayed as, brimming with exuberance

revelling in some acrobatic stance, flying high or huddled together in a

tight squeeze or moulded into a knot. Revealed with curvaceous body

forms and projected suppleness of limbs they exude an air of pride and

elegance.

A very interesting article written by Shanthi Balasubramaniam

(electronic source, used also for other information and photographs)

titled ‘Teaching of drawing in Ceylon’, gives us a clue as to how this

quaint art form may have evolved firstly in India and then transmitted

into Sri Lanka.

According to her, the early art Gurus, as part of the drawing course,

taught the gola, their students, drawing of curious combinations, in

particular, those known as ‘Nari combinations’. It may be noted however,

that in the course of transmission of these art motifs to Sri Lanka, the

label ‘Nari Kunjar’, by which these were identified within the Indian

art context, appears to have lost its currency. They are now

differentiated largely by the number of participating women. According to her, the early art Gurus, as part of the drawing course,

taught the gola, their students, drawing of curious combinations, in

particular, those known as ‘Nari combinations’. It may be noted however,

that in the course of transmission of these art motifs to Sri Lanka, the

label ‘Nari Kunjar’, by which these were identified within the Indian

art context, appears to have lost its currency. They are now

differentiated largely by the number of participating women.

Their skills were transmitted through parampara tradition from father

to son. According to her, the Kammalar came to Sri Lanka, either of

their own accord or were brought down as part of conquests of the

Sinhalese kings.

It can be assumed that both the Ridi Vihara and the Dalada Maligawa

temples where this specific art form is present may have had the impact

of South Indian influence in light of their close association with the

Kandyan Kingdom where that influence was dominantly felt.

In passing it may be mentioned that the other known location

revealing this art form, is Kande Vihara, a temple dated to 18th century

A.D, located few miles off the town of Aluthgama. She also points out

that the Kammalar, south Indian master craftsmen had a major say in the

early teaching of art and combinations of the Kunjar art form.

That is, Saptha-Nari Kesara - seven women Lion, and Nava-Nari

Vrashabha -nine women Bull. Both these reveal a major drift from the

most iconic motif used in this art form: the Nine Women Kunjara, (the

Elephant). In conclusion it may be said that in India this art form

continues to grow with a host of innovative additions. Women no longer

are the primary participants, as seen from the drawing of the Pashu

(Animal) Kunjar. It is filled with a ‘zoo’ of animals and reptilian

forms and it reveals somewhat of a grotesque portrayal.

|