|

Buddhist Spectrum

Doctrines of the Buddha’s six contemporaries

Lionel WIJESIRI

There are references in Buddhist literature to some six senior

contemporaries of the Buddha, for instance, samannaphala-sutta (the

second sutra in the Digha Nikaya). It appears from the context of these

references that Ajatshatru, the king of Magadha, had met a number of

these teachers and asked them each separately to state in clear and

unambiguous terms the result of their ascetic practices.

|

|

The

Buddha’s first followers |

At that time, all of them were well known in the country as founders

of religious schools, each having a large following. Their names and the

doctrines they upheld are briefly stated in the samannaphala sutta. It

is interesting to study their views in order to understand correctly as

well to appreciate the views of the Buddha.

Of these six thinkers, Mahavira (also known as Nigantha Nathaputta)

was the founder of Jaina tradition. He was slightly older than Buddha.

His ethical code consisted of five rules: not to kill living things, not

to take articles of use unless they are given, and not to tell a lie,

not to take a wife or to lead a celebrate life and not to have worldly

possessions except basic clothes.

According to Jaina sources, however, Jainism is not a purely ethical

system, but also a philosophy based on the doctrine of many

possibilities, known as Anekanta or Syadvada. The doctrine looks at two

aspects of everything, the eternal and the non-eternal. The soul

undergoes migration according to good or bad deeds. As Jainism regards

the existence of jiva in everything, it enjoys such behaviour as does

not cause injury to any jiva.

The soul becomes impure and is engulfed by samsara if it is subjected

to the influence of sense objects. In order to keep the soul pure from

their contamination, and to secure its release, it is necessary to

practice restraint. To achieve this stage, one must resort to or acquire

right knowledge, faith and conduct.

Buddhist sources do not agree with the Jaina doctrine, particularly

its idea of overcoming sin and its restraint on movements.

Other teachers

The second contemporary of the Buddha was Makkhali Gosala. He

belonged to the select of the Acelakas or naked ones, and, as the as the

first part of his name indicates, carried a stuff of bamboo. It is said

that he was for some time a disciple of Mahavira, but later broke away

from him. Afterwards he probably founded an independent school known as

Ajivika School.

The doctrine advocated by Gosala is styled samsara visuddhi or the

doctrine of attaining purity only by passing through all kinds of

existence. Gosala did not believe that there was any special cause for

either the misery of human beings or for their deliverance. He did not

believe in human effort, and held that all creatures were helpless

against destiny.

He maintained that all creatures, whether wise or foolish, were

destined to pass through samara, and that their misery would come to an

end at the completion of the cycle. No human efforts would reduce or

lengthen this period. Like a ball of thread, samsara had affixed term,

through which every being must pass.

The other four teachers, who are mentioned as contemporaries of the

Buddha, did not leave their mark on posterity as did Mahavira and to a

lesser degree, Gosala. Of these four, Purana Kassapa held the doctrine

of Akriya or non-action. He maintained that a man did not incur sin

through actions, which were popularly known as bad, e.g., killing,

committing theft, talking another man’s wife, or telling a lie. Even if

a man killed all the creatures on earth and raised a heap of skulls, he

incurred no sin. .

Ajita keshakambalin, the fourth contemporary of the Buddha, did not

believe the utility of gifts, in sacrifice, the fruits of good and bad

acts, the existence of heavenly worlds or persons possessing higher or

supernatural powers. He held that the body consisted of four elements,

into which it dissolved after death. He also held that it was useless to

talk of the next world; that both the wise and ignorant die and have no

further life after death. His doctrine may be styled Ucchedavada.

The doctrine of Pakudha Kaccayana, fifth contempory, may be called

Asasvatavada. According to him, there are seven elements which are

immutable, and do not in any way contribute to pleasure or pain. The

body is ultimately dissolved into these seven eternal elements.

The last among these teachers is Sanjaya Belatthiputta. His doctrine

is known as Viksepavada, or a doctrine, which diverts the mind from the

right track. According to the Samannaphala sutta, he always declined to

give categorical answers to problems facing the human mind. There are a

number of unexplained and unanswered questions that have always

exercised the mind of man and have frequently been mentioned in Buddhist

literature, which Sanjaya never even attempted to answer. According to

the Buddha, his skepticism is derived from both the fear of falling into

error and the ignorance of giving answer to any question put to him for

discussion.

This extreme skepticism (vicikicchaa), according to the Buddha, is a

mental hindrance, fetter or defilement, which will lead to

non-development towards achievement of its intellectual and spiritual

goal or to non-productivity of mind (cetokhila).

Aajiivikism, like Materialism, is a school of Naturalists. The

well-known founder of this school is Makkhali Gosaala. He believed in

the ultimate reality of matter, on one hand, and admitted the continuity

of human existence after death, on the other. Thus, they differ from

Materialists from the charge of nihilism. The naturalist philosophy of

Aajiivikism is covered in three important concepts, viz., fate (niyati)

species (sangati) and inherent nature (bhaavasvabhaava).

Fate (niyati) is the principle of coming into existence. Species

(sangati) determines species of a being as a human or an animal. And

inherent nature (bhaavasvabhaava) determines characteristics and nature

of that being. The major Buddhist rejection of Aajiivikism is on the

ground that the latter does not believe in human effort on the part of

individual.

The Aajiivikism’s rejection of human effort, thus, entails the denial

of the freedom of will. Following this, purification is impossible by

one’s own transformation but through the fixed cycles of existence

(saasaara-suddhi). Thus it falls into the form of past-determination

(pubbekatahetuvaada), a determined theory against moralism through human

effort in the present, and of the theory of external causation

(parakatam). Jainism as systematized by Nigantha Nataputta, is different

from Buddhism in terms of philosophy and ethics.

So far as ethics is concerned, Mahaaviira seems to ignore the

emphasis on the importance of psychological motive (chetana) of the

moral action (karmakiriya), as uniquely does the Buddha. For Mahaviira,

bodily action performed with or without one’s intention will produce

equal consequence. Mahaaviira appears to believe in partially biological

determination and partial human action, when he says “things are

partially determined and partially undetermined”. His ethical theory can

be, thus, grouped under past-determination (pubbekatahetuvaada), a

deterministic theory explaining every human experience is due to past

action, which is condemned by the Buddha as against human cultivation of

ethics. Another ground on which the Buddha rejects Mahavira’s theory of

moral action (kiriyavada) is the latter’s advocating non-doing and

expiating one’s past actions by extreme austerities or

self-mortification (attakilamathaanuyoga) as a means to attain

liberation, which is painful, ignoble and unbeneficial.

If the history of the philosophical thought currents at the time were

surveyed, it would be clear that the Buddha had to face thinkers who

held extreme views of the different types mentioned above and each of

them had their own answer to them. Mahavira answered the problems in

terms of his Anekantavada or Syadvada, while the Buddha’s answer was

based on his paticca-samuppada. While Mahavira clung to the doctrine of

Attakilamatha or self mortification, as against Kassapa, Ajita, Gosala

and Sanjaya, the Buddha preached the Majjhimapatipada or the middle

path.

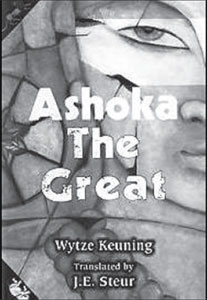

Book Review

Life and times of Ashoka

Title: Ashoka the Great

Author: Wytze Kuening

Translated from Dutch:

J Elisabeth Steur

Published: Rup publications

India Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi

Page count: 1060 pages

The publication of Ashoka the Great has a dual historical

significance. First, it resuscitates a Dutch Trilogy written in

Netherlands from 1937 to 1947 during the tumultuous years of the Second

World War by Wytze Keuning, whose voluminous work was not known even to

his family while his other novels were apparently known.

It needed persevering research in her home-town by the translator

until all three volumes could be found. Second, the laborious task of

elaborating the life and times of Ashoka in three volumes reveals the

degree of approbation which the third Mauryan Emperor had received from

Western scholars. As far as Netherlands was concerned, a popular play on

Ashoka and the Kalinga War called Asoca, a Buddhist Play in Four Acts

was published by G. Gonggrip in 1921. It needed persevering research in her home-town by the translator

until all three volumes could be found. Second, the laborious task of

elaborating the life and times of Ashoka in three volumes reveals the

degree of approbation which the third Mauryan Emperor had received from

Western scholars. As far as Netherlands was concerned, a popular play on

Ashoka and the Kalinga War called Asoca, a Buddhist Play in Four Acts

was published by G. Gonggrip in 1921.

In 1879, Edwin Arnold wrote in his Light of Asia

And where he [the Buddha] passed and what proud emperors

Carved his words up on the rocks and caves.

Colonized glory

In 1890, Romesh Dutt of India stated, “No greater prince had ever

reigned in India since the Aryans first colonized and no succeeding

monarch equaled his glory, if we only except Vikramaditya of the 6th

century and Akbar the Great in the 16th century.” Bishop Copleston in

1892 said, “He was not merely Constantine of Buddhism, he was Alexander

with Buddhism for the Hellas, an unselfish Napoleon with ‘mettam’ in

place of ‘gloire.’” Vincent Smith writing a monograph on Asoka

concluded, “He was strong enough to sheath his sword in the ninth year

of his reign, to treat the unruly border tribes with forbearance, to

cover his dominions with splendid buildings and devote his energy to the

diffusion of morality and piety.”

The most eloquent of all was H. G. Wells who in his ‘Outline of

History’ wrote, “Amidst the tens of thousands of names of monarchs that

crowd the columns of history, their majesties and graciousness and

serenities and royal highnesses and the like, the name of Asoka shines,

and shines almost alone, a star.”

Did WytnzeKeuning, a headmaster of a school in Groningen

(incidentally the home-town of the translator), have access to all this

to be inspired and motivated to spend ten years of his life to write

three novels on this Indian emperor of the third century before Christ?

From where did he get the information? Whom could he have consulted at a

time when a deadly war cut communications not only with India but also

the neighbouring countries? Intense work

There is no doubt that he had access to the most reliable data on

Ashoka. As Elisabeth Steur says with reference to my own intense work on

Ashoka, “It was, though, not until I found the last comprehensive study

of Ashoka by Ananda W. P. Guruge (Asoka the Righteous: A Definitive

Biography, 1993) that I discovered that whatever was known about Ashoka

for certain was woven into the stories of the books. Then the last

doubts I may have had were erased. The books had to be translated.”

The trilogy of Keuning dealt with the life of Ashoka in three phases:

1. Ashoka, the Wild Prince

2. Ashoka, the Wise Ruler

3. Ashoka, the World’s Great Teacher

All three now appear in English as “Ashoka the Great.” It is indeed

very thoughtful that they are published together in a single volume.

What baffled me as I read several versions of ElisabethSteur’s

translation of the three novels over a decade or so of our close

association was that Kuening knew not only the literature on Ashoka but

also the voluminous research in Europe, which by the beginning of the

twentieth century, had shed much light on the social conditions of

ancient India. His family found as one of his sources the excellent work

of Radha Kumud Mookerji, published in 1928.

There is no doubt that he had made an in depth study of the

background. He had access to much of the Sanskrit and Pali works on

Ashoka in addition to his inscriptions which Mookerji had included in

his work. For example, he shows great familiarity with the Divyavadana

account that Ashoka was not good-looking (p. 5) as well as his

assignment to quell a rebellion in Taxila to which only the Sanskrit

sources refer. Similarly, Sumana as Ashoka’s elder brother is known from

only Pali sources. Keuning has also portrayed accurately the political,

military and diplomatic relations between the Mauryan Empire and the

Greek Kingdoms to its west as reflected in the Ashokan inscriptions.

Deep scholarship

There is no doubt about the authenticity of the narrative and the

research leading to his novels had been perfect. The appendices reveal

the depth of his scholarship which covered practically all fields of

Indology known at the time. For example he defines Ataman on 328 pp as

follows: “principle of explanation of the world; World-soul, All-one

(Atman), that unfolds itself in all living beings and so is only to be

known by the human being in his inner-being (atman). Upon this the sutra

of soul being one is founded. ‘Tat tvamasi’, i.e. That Thou Art, express

(sic!) the identity of the world-soul and the human-soul unity of life

and spirit.” Equally fascinating are his notes on Gods (p.329),

Sacrifice (p. 330), Stages of Life (p. 330), the intricacies of the

Indian drama (pp. 880 ff.) and how he weaves the story of the Buddha’s

instructions to Kisagotami on the inevitability of death by sending her

to get a mustard seed from a home that had not experienced death (804

-805 pp).

Though he had never set foot in India, he had obtained, through

systematic study of a large volume of scholarly treatises in English,

German, French and Dutch, a fairly comprehensive understanding of the

social and religious environment in which Ashoka operated in India of

the third century before Christ.

Keuning has crafted his novels well as a tool for sharing his

understanding of the emperor as well as the history and culture of

India. He had purposely highlighted the prevailing religious dissensions

of the time which required Ashoka to issue an edict on interfaith

harmony and understanding in Rock Edict XII and another prohibiting

animal sacrifice (RE I).

Early scholars

How he handled Ashoka’s contribution to Buddhism clearly shows his

familiarity with the remarks made by early Indian Ashokan scholars, who

for an unknown reason found it necessary to ignore and even spitefully

denigrate the Sri Lankan Pali sources without which they would have not

even identified who Asoka was. While giving Ashoka credit for the purge

of the Sangha which is mentioned in three of his Minor Pillar Edicts,

Keuning leaves the thousand-member Third Buddhist Council and the

Buddhist missions – which are not referred to in any inscription found

so far – as activities of the Buddhist Sangha (p. 794).

Interestingly, Keuning narrated the account of the mission of

Mahindra to Lankan very much in the way it was dealt within the Sri

Lankan chronicles – the Dipavamsa and the Mahavamsa. (p. 759 ff. and 823

ff). Of course, he did add his own explanation on why Mahindra as the

first-born did not become the heir to the throne and how the mission to

Lanka was negotiated between Ashoka and Devanamapiya Tissa of Sri Lanka.

The reader will be pleasantly surprised by Keuning’s skill in

generating suspense through which his interest is sustained in the

account of the tragedy of blinding Kunala and the execution of its

perpetrator, Queen Tissarakshita, by fire that brings the story to a

close. The reader, who is not fully conversant with the life and career

of Ashoka as a truly exceptional monarch, would find Keuning’s novels

very instructive. They are both educational and entertaining. The

trilogy as a whole is a masterpiece.

A review of this magnificent trilogy cannot end without noting the

tenacity of its translator, Elisabeth Steur, who toiled under most

trying circumstances to have it translated into English and published.

That she tried to do it in India and succeeded is to her credit. Few

people would have had the patience, perseverance and firmness of

determination to overcome the many obstacles.

As a dedicated student of the manifold contributions of Ashoka to

humanity, I salute Wytze Keuning for giving us his own view of this

eminent monarch in his original Trilogy and Elisabeth Steur for bringing

it to our attention after nearly seven decades. Their joint effort must

be gratefully appreciated.

Dr Ananda W P Guruge

Meditation for daily life:

Strengthening concentration power

That is why we must do it throughout the day in a balanced manner.

Otherwise we will be spending the major portion of the day in a manner

in which the sins do not get worn off.

If we practise a meditation throughout the day we do so in a manner

in which sins get worn off. Therefore do not waste time. Even an

individual practicing Samadhi should do the same. If he thinks “I now

have the Samadhi” and neglects to meditate the pleasure he gets from the

Samadhi may get weakened. After sometime even the Samadhi might leave

him and he will lose the comfort he was receiving.

|

|

Meditation

leads to a peaceful mind |

Therefore what the person with the Samadhi should do is thinking of

practicing the Samadhi in the morning, daytime and night in a balanced

manner in order to maintain the Samadhi well and to generate other

merits which can be attained from Samadhi. The more one practises

Samadhi, the more he develops Samadhi, the more will be the comfort that

is obtained.

Samadhi happiness

Now let us think of an Arahant. He has annihilated all Raga, Dosa and

Moha. He can achieve a lot of happiness from Samadhi. When one remains

in Samadhi he is in immense comfort. When the Arahant gets back from the

Samadi his face is said to be very pleasant. If it is so with regard to

Arahants there is nothing to talk about ordinary people. If the person

who has annihilated Raga, Dosa, Moha enjoys immense joy when in Samadhi,

how much happiness will an individual with Raga, Dosa and Moha enjoy

when in a Samadhi?

Therefore do not develop laziness. Do not neglect to do it saying

that it is difficult. After a time one gets used. It is true that it is

difficult at the beginning. It is something like this. Many people find

it uncomfortable when wearing a new pair of shoes. Some people develop

shoe cuts. After some time there are no signs of that discomfort. It

becomes very comfortable.

Similarly when starting to practise meditation it is difficult at the

beginning. But after a time one gets used to it and it becomes

comfortable. We practise one meditation and start a new one.

It becomes difficult. It is difficult when starting something new. An

individual used to wearing shoes buys another pair. Then the discomfort

will come again.

Similarly when an individual used to one meditation starts a new one

discomfort arises. Why? Because there is no practice. Along with

practice the discomfort goes off. Sometimes laziness may exist in the

morning. The meditation may not develop. But do not think of it as not

developing. Sleepiness may come. Don’t get overcome by it. Practise with

the feeling “I must get used to this”. As time goes on things become all

right gradually. One gets used.

‘Doing it later’

It is the same in the daytime too. There may be sleepiness. Do not

yield to it. Don’t think. “It is difficult now. I am feeling sleepy”.

You may feel like doing it later. Do not take it that way. Think “I must

practise now” and practise. Later discomforts will go off and comfort

will come.

In the night one may feel “Now I am tired. I am feeling sleepy”. Do

not yield to it. Leave it out and practise. In that manner if we

practise systematically during morning, day and night it will be

possible for us to meditate, to attain a Samadhi at any time. Then we

can spend the entire day with a delightful mind. That comes along with

the practicing of Samadhi.

Samadhi is the path to Nibbana. Path to Nibbana is what helps us to

annihilate sins. Do all our sins get annihilated at the time we start

practicing the Dhamma? What have we got to do to annihilate sins? We

should develop the path to Nibbana. Path to Nibbana is Samadhi. Sins get

annihilated by developing Samadhi. Therefore we must develop the ability

to practise the Samadhi, to remain for a long time in the Samadhi. But

it has to be done systematically.

Why? It is the place where sins get worn out. Don’t we feel

comfortable when we wet our body with a little water during the hot

noon? After sometime we feel uncomfortable again. If one stays at a

place where there is water always will the heat be a problem for him?

No. In the same manner if we are always engaged in Dhamma and

meditation, if we practise Samadhi extensively, will the torments

arising from sin come? No. Such torments start getting annihilated.

Worn off sin

Then the sin gradually gets worn off. Why? Because we do not maintain

the sin. What we maintain is the merit. More and more we maintain merit

more and more sin gets worn out. That is why we should practise Samadhi

in the morning, daytime and night systematically. That has to be

remembered and practised. At the start it is difficult to do it for

hours. Don’t even think of doing so.

Don’t even do. Then we will be unsuccessful. Practise little by

little at the beginning. After sometime we will realize that it is

successful. If not we will not be able to reap the immense benefits of

Samadhi. We fail to acquire the merits not achieved so far. Therefore we

hope you will understand the facts indicated in this sermon. We hope you

will make use of them. If we get these facts clarified and adapt to our

lives we will be able to get some solace to our lives. In such a case we

get the opportunity to get that solace at the maximum level.

Think of even getting a maximum solace. We hope that opportunity will

dawn on you. We have the strong wish that you will practise the Dhamma

and mediate and thereby at least suppress the torments experienced due

to the defilements and remain in comfort. We wish that you will get rid

of the discomfort experienced due to Raga, Dosa and Moha. I wish

earnestly that you will get the ability someday to completely annihilate

Raga, Dosa and Moha. Leave aside completely annihilating. We wish that

you will realize the state of remaining with thinned down Raga, Dosa and

Moha.

(Compiled with instructions given by Ven Nawalapitiye Ariyawansa

Thera)

[email protected]

|