Translation Prizes 2012

Adrian Tahourdin

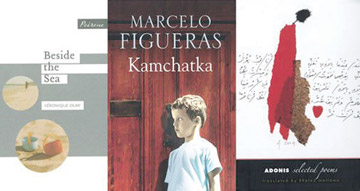

Two of this year’s translation prizewinners were first published in

their original languages in 1947, which hints at the intriguing prospect

of a world library out there waiting to be rendered into English. Four

of the five awards – the Arabic, French, German and Spanish – are annual

fixtures, joined on this occasion by the Flemish.

Adonis (Ali Ahmad Said Esber) was born in 1930 in a village in

western Syria. According to his latest translator Khaled Mattawa, he was

“unable to afford formal schooling for most of his childhood”; instead

he learnt the Qur’an and memorized classical Arabic poetry.

He later gained a degree in philosophy from the University of

Damascus. In 1955–6 Adonis was imprisoned for membership in the Syrian

National Socialist Party, after which he and his wife settled in Beirut

and became Lebanese nationals. He now lives in Paris. He later gained a degree in philosophy from the University of

Damascus. In 1955–6 Adonis was imprisoned for membership in the Syrian

National Socialist Party, after which he and his wife settled in Beirut

and became Lebanese nationals. He now lives in Paris.

For several years Adonis has been talked of as a possible Nobel

Prize-winner, yet he remains, as Eric Ormsby pointed out in a review of

an earlier translated collection, A Time Between Rose and Ashes (TLS,

April 14, 2006), “relatively unknown in the English-speaking world,

largely for lack of good translations”.

Ormsby prefaced that comment with the observation that Adonis’s

“impact on the Arab literary world has been huge, if controversial”, and

that he is “deemed the most provocative and successful innovator of

Arabic verse in our time”. In the words of the critic Marilyn Hacker,

Adonis is “recognized as one of the most important poets and theorists

of literature in the Arab world . . . . His influence on Arabic poetry

can be compared with that of Pound or Eliot on poetry in English,

combined, however, with a radical and secular critique of his society”.

Khaled Mattawa has been working on his translations of Adonis’s work

for two decades and wins the Saif Ghobash–Banipal Prize for translation

from Arabic for his compendious Selected Poems (399pp; Yale University

Press; $30; 978 0 300 15306 4). Mattawa, who is himself a published

poet, writes of his approach: “Much of Adonis’s early poetry makes

frequent use of rhyme, but I have not tried to replicate his rhyming.

The same can be said for meter. Given that Arabic metrical feet are

quite different from Western ones, I have not stuck to any metrical

pattern, even when the poems are metrically composed”.

Adonis’s work is acknowledged to be densely allusive, drawing on the

work of the great Arab poets of the past, while also paying tribute to

European poets such as Nerval and Baudelaire.

Although Mattawa’s Introduction is informative, his notes (four pages

to nearly 400 pages of poetry) sell the reader a little short on the

influences. Where the work is baffling – the sense in lines such as “We

are a single face, / my shirt is not made of apples and you are not a

paradise”, or “My neck is a ladder climbing the horizon / and my head is

a blue sun”, is not immediately evident – a little more assistance from

the translator would have been welcome. Mattawa suggests that Adonis

“has entrusted language with the role of stretching our conceptual

faculties while trusting the reader’s natural ability to occupy new

realms of thought out of sheer curiosity”.

The work, as translated into English, rarely appears overtly

political, although Mattawa explains that The Book of Siege (1985) found

its source in the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982. This collection

includes a lengthy meditation (in long lines) on enforced darkness,

“Candlelight” – “I return to the warm companionship of the slim candle .

. .” . Elsewhere he writes “‘I will never return to my country,’ said a

young woman almost crying. / Indeed, how miserable it is to be an Arab

today”. There is lyricism aplenty too, as in “The rose leaves its

flowerbed / to meet her / The sun is naked / in autumn, nothing except a

thread of cloud around her waist”.

Mattawa points out that “Adonis has been a consistent critic of

Western societies’ and governments’ treatment of the rest of humanity”,

and that he is “a seasoned and controversial public intellectual . . .

[but] first and foremost a poet”. In August last year, he urged

President Bashar al-Assad to step down.

Louis Paul Boon (1912–79) was a Flemish author of mainly historical

epics and scabrous novels. Very little of his work has been translated

into English, which makes Paul Vincent’s version of My Little War

(125pp. Dalkey Archive Press; paperback, $12.95; 978 1 56478 558 9)

particularly welcome.

The book, a series of vignettes, gives a vivid impression of Belgian

life under German occupation: “Now the Germans were here, and really

people shouldn’t go around saying that all Flemish nationalists were in

the pay of the Germans . . .”. We hear about Mr Swaem who runs a factory

that made boots throughout the war, first for the Organisation Todt and

then for the Wehrmacht, and of “Boone, who lived next door and sold

tires to the German army and had earned a fortune from it”. Elsewhere,

we learn that

“. . . there’s been an assassination attempt on Hitler and there’s a

revolution going on and they’re already fighting in the streets of

Hamburg and Berlin and Kiel, the sailors are destroying their own

weapons and the army is fighting against the S.S. – there’s been a

revolution just like in 1914–18 and the war is over. And it’s not true,

Hitler isn’t dead and there isn’t a revolution just like in 1914–18 and

the war isn’t over – the Germans commandeer all the remaining cars and

the first V-1 flies overhead.”

The novella first appeared in Flemish in 1947 as Mijn kleine oorlog.

Vincent, winner of this year’s Vondel Prize, has produced a fluent and

idiomatic version (apart from one jarringly anachronistic note, where he

refers to “African American or Native American” soldiers). In a

Translator’s Note, he explains that the book had a “three-stage

publishing history”, during which the author “toned down the Flemishness

of its idiom, and bowdlerized some of its physical and sexual

explicitness. Ironically, Boon’s (successful) accommodation of a wider

readership in the Netherlands attracted growing criticism in Flanders,

where he was seen by many as compromising his youthful revolutionary

principles”. Vincent has chosen the 1960 Dutch edition.

Comedy in a Minor Key was also published in 1947, as Komödie in Moll.

Its author Hans Keilson (who died last year, aged 101) was a

psychiatrist who worked with Jewish survivors of the Holocaust.

He had fled Germany in 1936 and settled in Holland (his parents were

to die in Auschwitz).

The novella is set in Amsterdam during the Second World War and tells

the story of Marie and Wim, a couple in their twenties who have taken in

a refugee, Nico, a Jewish perfume salesman.

The situation produces comic moments, as when the cleaning lady

mistakenly opens the wrong bedroom door and is confronted with him (she

doesn’t give him away).

But there is pathos too: Nico is in poor health, and the doctor who

pays regular visits ingeniously suggests to Marie and Wim that they

explain to their neighbours that he calls on them in order to listen to

music. Nico doesn’t survive the novella and the couple’s attempts to

dispose of his body clandestinely produce further dark comedy. Damion

Searls wins the Schlegel-Tieck Prize for Translation from German for his

elegant version.

Véronique Olmi’s punchy, short first novel Bord de mer was published

in 2001 by the admirable Arles-based firm of Actes Sud. (Olmi was born

in 1962.) The narrator of Beside the Sea, a single mother who is being

treated for depression, takes her two sons Stan (nine) and Kevin (five)

for a first holiday to an unnamed seaside town, where it rains

ceaselessly – “The rain was spattering against our window, poison

released from above” (later, raindrops are likened to “gobs of saliva”).

The Hindu

|