Poly sacks, post-harvest loss and profiteers

Last month, in the middle of the Christmas festive season, the price

of vegetables in Colombo and other urban areas skyrocketed. The reason

was that the government introduced a regulation requiring the transport

of all vegetables to be carried out in plastic or wooden crates rather

than gunny bags (hardly ever used nowadays) or polythene sacks. Last month, in the middle of the Christmas festive season, the price

of vegetables in Colombo and other urban areas skyrocketed. The reason

was that the government introduced a regulation requiring the transport

of all vegetables to be carried out in plastic or wooden crates rather

than gunny bags (hardly ever used nowadays) or polythene sacks.

The regulation was introduced in order to reduce the incidence of

spoilage in transport and handling and was expected to benefit farmers

and vendors in the long run. This followed on from studies which showed

that about half all post-harvest losses, which ranged from 16 percent

(ladies fingers) to 41 percent (cabbages and leeks), in the steps in the

marketing chain between the

The sources of post-harvest loss in the collection and transportation

stages were identified as exposure to sun, rough handling during loading

and unloading, transportation in poly sacks, tight packing and

overloading, compression damage during packing and stacking, damage due

to vibration and heat build up during transportation.

Vegetable farmers

The Institute of Post-Harvest Technology (IPHT) found that

transportation losses could be reduced from 15-20 percent with the use

of poly sacks to 3-6 percent with the use of plastic crates. The profit

from a single lorry load was found to increase by 25 percent.

Three-wheelers and Land-Masters were exempt from the law, which applied

only to lorries. The transporters, refusing to comply, went on strike

(and in certain areas, also on the rampage) until the regulation was put

on hold.

|

|

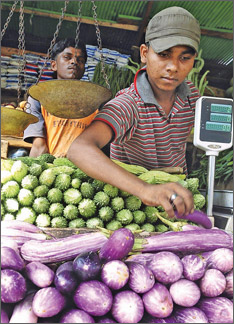

Vegetables

for sale |

This episode illustrates the extent to which vegetable farmers are

still dependent on middlemen. Even in times of glut, the middlemen,

while buying the farmers’ produce dirt-cheap sell it in Colombo at very

high prices. Consequently, Sri Lanka has one of the highest levels of

retail vegetable pricing in the region, surpassed only by Maldives.

Not so long ago, when farmers were receiving only about Rs 10 per

kilo of Tomatoes, the price in Colombo was Rs 50 per kg. It does not

take much arithmetic to figure out that the Rs 35 difference is far

higher than warranted by the cost of transport from Dambulla or Nuwara

Eliya (which is in fact about a rupee per kilogram).

The old Marketing Department (MD) was established to combat the

extreme exploitation of farmers by middlemen and to reduce the

occurrence of debt-peonage. At the time, most farmers were in the thrall

of the middlemen, who advanced them money at usurious rates for their

produce and collected it very cheap.

The problem of usury has been alleviated somewhat as banks

(particularly the state-owned banks) have proliferated in rural areas,

so that finding credit is not as big a problem as it used to be.

Nevertheless, the problem of exploitation by the transport-middleman

remains.

Capital accumulation

Given the small average size of Sri Lankan agricultural holdings,

transport to the market remains the central obstacle to achieving high

rates of capital accumulation in the sector; the surplus from

cultivation is taken mainly by the profiteer in the middle.

The IPHT research indicated that the implementation of the packaging

change from poly sacks to crates at the farmer’s level was impractical.

Farmers could not afford the cost of crates – an almost 18-fold increase

over poly sacks, even though the overall lifetime cost is only 15

percent of the latter.

Indeed, the average farmer cannot afford to invest in all the

measures the IPHT says can reduce post-harvest loss; for example,

packing house facilities having basic requirements such as washing

tanks, sorting and grading devices and cold storage facilities. They

could not even afford to install the low-technology (using a clay pot!)

evaporative cooling unit, developed by the IPHT and the University of

Peradeniya.

Obviously the onus should be on the middleman to introduce new

technologies and better practices to reduce post-harvest loss. However,

it appears that the middlemen, the collectors, transporters and vendors

are chary of doing so.

Their reasoning is not hard to find. The profit levels estimated by

the IPHT for the operations of middlemen were far below the actual

figures.

Packaging technology

Loss in transportation is minimal in comparison with the return, so

investing in more technology is a mere burden without commensurate

returns. The levels of profit can be measured by the fact that the big

supermarket chains are often able – despite higher overheads on such

things as air conditioning and refrigeration - to supply vegetables at

the same or lower prices as at retail greengrocers’ boutiques.

This is because they buy direct from the producers or from collection

centres, thereby eliminating the bulk of the supply chain. The MD was

established on precisely this premise, with the additional aim of

providing storage and packaging technology (for example its canneries)

in order to have year-round goods supply. Since the MD is no more, the

government shift its emphasis from the private sector to the

co-operatives.

The Co-operative Marketing Federation (Markfed) could become much

more active and step into the breach. It could establish the necessary

packing houses (complete with cooling facilities) close to the

producers, say at the central point in a village. This would enable

better packing and storage practices to be implemented at the base level

– as well as improved hygiene.

The co-op system could then become the hub of a vegetable supply

system oriented towards both producer and consumer - giving the former

high prices and the latter low ones.

Unfortunately, this is predicated on the response of the mafia of

vegetable middlemen. If this body of gentlemen can wreck such a small

thing as a regulation on the transport of vegetables, how far would it

go to prevent an effective solution to the needs of both producers and

consumers of vegetables?

|