|

Parnassian Poetry :

‘The roll, the rise, the carol, the creation’

In our consideration of the “Greats” of English poetry we have

considered examples of their poetry which have undoubtedly prompted us

to acknowledge the greatness of their artistic achievement. In our consideration of the “Greats” of English poetry we have

considered examples of their poetry which have undoubtedly prompted us

to acknowledge the greatness of their artistic achievement.

This does not mean, however, that everything these poets wrote must

necessarily have been great. Eliot did, after all, say of Lawrence that

he had to write a lot badly in order to write well sometimes. We might

even be justified in saying, along the lines of the nursery rhyme, that

when Lawrence is good he is very good, but when he is bad he is horrid.

As evidence we would only need to juxtapose his “Lizard” with his

“Snake.”

The preponderance of Lawrence’s “bad” poetry is, perhaps, an extreme

case, but the fact is that the collected works of any great poet

include, along with a healthy abundance of great poems, a considerable

number of lesser ones. Even the Sonnets of Shakespeare are not exempt

from this observation. This certainly does not demean the achievement of

these poets. Our appreciation of their greatness can only be enhanced by

our ability to identify any of their works that do not contribute to it.

But how are such works to be recognised?

Spontaneous overflow

This is where GM Hopkins, while still a 20 year old undergraduate,

comes to our assistance. Referring, in a letter to his friend Baillie,

to the subject of poetic diction, he makes a distinction between “the

language of inspiration” and what he calls “Parnassian” language. He

explains the latter as being the manner in which a great poet expresses

himself when he is writing according to the style that he has perfected,

and which he alone can reproduce, but without the inspiration that

raises his poetry from the level of competence to that of greatness. By

“inspiration” he means that “mood of great, abnormal in fact, mental

acuteness, either energetic or receptive, according as the thoughts

which arise in it seem generated by a stress or action of the brain, or

to strike into it unasked.”

|

|

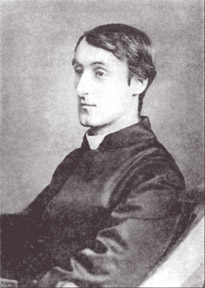

G M Hopkins |

If we were to resort to Wordsworth’s convenient definition of poetry,

inspiration could be said to refer to the “spontaneous overflow of

powerful feelings” that is meant to follow “emotion recollected in

tranquility” or the reconsideration, for poetical purposes, of an

emotional experience. Inspiration is, in fact, the condition in which

the poetic imagination seems to take over the poet’s creative process,

enabling him to arouse in us an emotional response corresponding to the

emotional experience he is describing.

Hopkins goes on to say that when a great poet “palls” on us, it is

because his poetry has become Parnassian or uninspired. He adds: “No

author palls so much as Wordsworth; this is because he writes such an

intolerable deal of Parnassian.” Let us put this to the test. Here is

Wordsworth describing, in “Tintern Abbey”, the influence of Nature:

during his youth: “For nature then (The coarser pleasures of my boyish

days, And their glad animal movements all gone by,) To me was all in

all. - I cannot paint What then I was. The sounding cataract Haunted me

like a passion: the tall rock, The mountain, and the deep and gloomy

wood, Their colours and their forms, were then to me An appetite: a

feeling and a love, That had no need of a remoter charm, By thought

supplied, or any interest Unborrowed from the eye.”

And here he is in “The Prelude”, his enormous autobiographical poem,

describing very much the same thing: “Oh! Soul of Nature, excellent and

fair, That didst rejoice with me, with whom I too Rejoiced, through

early youth before the winds And powerful waters, and in lights and

shades That march’d and countermarch’d about the hills In glorious

apparition, now all eye And now all ear; but ever with the heart

Employ’d, and the majestic intellect, Oh! Soul of Nature! That dost

overflow With passion and with life!”

The subject and the form (iambic pentametred blank verse) are the

same, but the quality of verse in the two passages is entirely

different. In the first Wordsworth is, in his own words, “a man speaking

to men”, the passage is in living speech as well as being descriptive.

Natural objects

As such, it recaptures for us the excitement that the youth felt amid

Nature. Consider the way the rhythm changes to support the exclamations,

eg. “Haunted me like a passion”; the way the natural objects crowd in

upon his memory – cataract, rock, mountain, and wood: and the way their

effect is described as if in the heat of the moment - “was all in all,

like a passion, an appetitie, a feeling, a love”. All this makes the

reflection of the last three lines sound logical and understandable. The

experience is heartfelt and the passage is clearly “inspired” by the

poetic imagination.

The picture changes with the second passage. The language is entirely

Wordsworthian and only he could have written it. Yet, in this case the

recollection of experience has not had the benefit of the participation

of the imagination.

Therefore the description of nature is somewhat generalised and

lifeless for all its eloquence, eg. “excellent, fair, powerful,

glorious, majestic”, none of which epithets convey a sense of actuality

or immediacy. The unwavering rhythm is not under any presssure from the

demands of expression. In fact, some words seem to be added on simply to

fill out the metre, eg “and fair......and countermarch’d” Thus we are

not touched, or emotionally affected, by the experience, and the passage

is obviously “Parnassian”. “Overflow with passion and with life” is

precisely what it does not do!

Such examples are obtainable, to a greater or lesser degree, from all

of the “Greats”, and the more we are acquainted with their inspired

poetry the better we will be able to identify their Parnassian. This, in

turn, will help us to appreciate how the creative imagination enables a

poet to harness his craftsmanship or stylistic accomplishment to produce

great poetry.

We have spoken much about the poetic or creative imagination in this

series, and this is how Coleridge authoritatively defines it: “The poet

brings the whole soul of man into activity...He diffuses a tone and

spirit of unity that blends and...fuses, each into each, by that power

to which we have exclusively appropriated the name of Imagination. This

power...reveals itself in the balance or reconciliation of opposite or

discordant qualities; of sameness, with difference; of the general, with

the concrete; the idea, with the image; the individual, with the

representative; the sense of novelty and freshness, with old and

familiar objects; a more than usual state of emotion, with more than

usual order.” MI Kuruvilla reckons this statement to be “the foundation,

the corner stone of modern literary criticism.”

Inspirational power

Hopkins himself rarely lapses into Parnassian, probably because of

his having identified the tendency so early in his career. Towards the

end, however, he was acutely conscious of a loss of inspirational power

and lamented this in lines such as the following:

“...birds build – but not I build; no, but strain, Time’s eunuch, and

not breed one work that wakes. Mine, O thou lord of life, send my roots

rain.”

“Sweet fire the sire of muse, my soul needs this; I want the one

rapture of an inspiration. O then if in my lagging lines you miss The

roll, the rise, the carol, the creation, My winter world, that scarcely

breathes that bliss Now, yields you, with some sighs, our explanation.”

The question we would like to leave you with, by way of a test, is

whether these lines, in which Hopkins describes his lack of inspiration,

are Parnassian or inspirational!

|