|

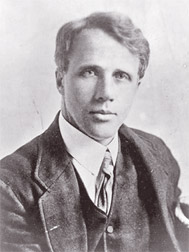

ROBERT FROST:

‘The fact is the sweetest dream’

Among MI Kuruvilla’s lectures that I remember best are those on the

North-American poet, Robert Frost (1874-1963). The first of his poems we

were introduced to was “Blue-Butterfly Day”, short enough to quote in

its entirety:

“It is blue-butterfly day here in spring, And with these sky-flakes

down in flurry on flurry There is more unmixed color on the wing Than

flowers will show for days unless they hurry.

“But these are flowers that fly and all but sing: And now from having

ridden out desire They lie closed over in the wind and cling Where

wheels have freshly sliced the April mire.”

This also serves to introduce us to Frost’s so-called naturalism. The

setting is rustic, the topic commonplace. The versification is

traditional - rhymed iambic. The diction is simple and unaffected. It

seems a straightforward nature poem. But is it?

The rhythm has a sad lilt that moderates the exuberance of the first

verse. This anticipates the butterflies’ eventual death in the mud,

their end seeming to proceed from their very joie de vivre, “having

ridden out desire.” It is the sadness of the brevity of life and beauty

in this world. Do the slicing wheels hint at man’s hand in this?

|

|

Robert

Frost |

In an essay entitled, “The Constant Symbol”, Frost declared about

poetry “that it is metaphor, saying one thing and meaning another,

saying one thing in terms of another, .the pleasure of

ulteriority....Every single poem written regular is a symbol small or

great...” In regard to his commitment to conservative prosody he

explained, “I have written my verse regular all this time without

knowing till yesterday that it was from fascination with this constant

symbol I celebrate.”

In “Mowing”, one of his most beautiful poems, there is a greater

personal involvement in the experience making the “symbolism” more

immediate. It is a partially rhymed sonnet: “There was never a sound

beside the wood but one, And that was my long scythe whispering in the

ground. What was it it whispered? I knew not well myself.” Note the

evocativeness of the language for all its simplicity. The sibilance

running through these lines recreates the swish of the scythe. Then,

after some speculation, comes the answer to the question: “Anything more

than the truth would have seemed too weak To the earnest love that laid

the swale in rows” and the conclusion: “The fact is the sweetest dream

that labour knows. My long scythe whispered and left the hay to make.”

That penultimate line, indicating that labour wholeheartedly

undertaken is its own reward, is far from being a moral appended to

justify a tale, as some critics have accused Frost of doing in his

poetry. The comment is the natural outcome of the poet’s being part of

the action. Interestingly, the line also explains Frost’s type of

symbolism. The “dream” of symbolic significance arises directly from the

uniqueness of the “fact” under consideration. It is like a further

development of Hopkins’ theory of Inscape, a matter, in Wordsworth’s

phrase, of “seeing into the life of things.”

The same can be said of “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”. When

the poet stops his cart to watch the woods “fill up with snow”, his

little horse “gives his harness bells a shake To ask if there is some

mistake.” Then comes the famous last verse (which Jawaharlal Nehru kept

displayed on his desk in his last years as India’s Prime Minister): “The

woods are lovely, dark and deep. But I have promises to keep, And miles

to go before I sleep, And miles to go before I sleep.” Kuruvilla

comments on this poem in his “Studies in World Literature”, “We are

aware of the moral value but we do at the same time hear the little

horse ‘give his harness bells a shake.’ So Frost was right when he said

that a poem begins in delight and ends in wisdom. The moral is fully

assimilated into the descriptive, concrete texture of the poem.”

“Mending Wall” is one of Frost’s shorter narrative poems. It is in

loose iambic blank verse. His style here is enriched by a quiet dramatic

sense and a mildly ironic manner. The poet and his neighbour have got

together to repair the wall that separates their properties. The poem

opens with the poet stating, “Something there is that doesn’t love a

wall”, and he repeats this when they come to a section where no wall

seems to be required. Yet the neighbour insists, uttering the truism,

“Good fences make good neighbours”, repeating this in the last line. We

realise that both viewpoints are right, but the inflexibility of the

brick-carrying neighbour makes him seem “like an old-stone savage armed,

(who) moves in darkness as it seems to me, Not of woods only and the

shade of trees.”

The implication is that the rigid exclusivity that individuals,

communities and nations tend to practice towards each other has a

primitive provenance that unfortunately prevails over the more flexible

openness that characterises true civilisation.

But there is also a darker, more tragic, side to Frost. “Design” is a

rhyming sonnet “I saw a dimpled spider, fat and white, On a white

heal-all, holding up a moth Like a white piece of rigid satin cloth -

Assorted characters of death and blight.”

The sestet asks the frenzied questions, “What had the flower to do

with being white, The wayside blue and innocent heal-all? What brought

the kindred spider to that height, Then steered the white moth thither

in the night? What but the design of darkness to appall? - If design

govern in a thing so small.” By a hideous concatenation of circumstances

these three entities have come together in the dark, all a deathly white

- even the usually blue, reputedly salutary, flower - to camouflage the

spider and trap the moth.

Rather like Thomas Hardy the poet supposes a sinister design behind

the seeming blindness of chance, whereby the innocent are invariably the

victims.Less terrifying, but no less tragic, is “The Most of It”. It is

the plea of one who is full of love for his fellowmen, yet feels himself

to be out of place “in this harsh world”, for a complementary concern on

the part of others.

“He would cry out on life, that what it wants Is not its own love

back in copy speech, But counter-love, original response.” Yet, “nothing

ever came of what he cried Unless it was the embodiment that crashed In

the cliff’s talus on the other side, And then in the far distant water

splashed...” But, “instead of proving human when it neared...As a great

buck it powerfully appeared” that shook the water off itself and

disappeared into the underbrush - “and that was all.”

The caring man remains alone, his expectations of sympathetic

recognition by his fellowmen are dashed, society is no better than an

unreasoning beast in its indifference to the initiatives of, in Henry

James’ phrase, its “vessels of consciousness”, those who represent the

potentialities of human experience.

MI Kuruvilla’s favourite poem, however, was Frost’s shortest,

“Devotion”: “The heart can think of no devotion Greater than being shore

to the ocean – Holding the curve of one position, Beating an endless

repetition.” Let his own comments conclude this article: “The calm

static lines and their flat recitation have created the stillness of the

‘position’ of the body and its ‘permanence’. The lines have the endless

monotony of waves along the shore and the simple loyal endurance of

love.” |