|

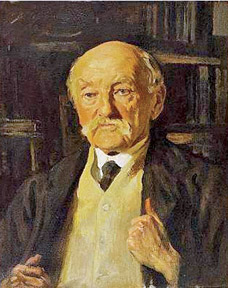

Thomas Hardy :

‘Love begotten by despair’

With Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) we are finally into the 20th century.

Although he was already 60 when it dawned, he only began to publish

poetry around the turn of the century, going on to do so at regular

intervals until the year of his death. It is as a novelist that Hardy

belongs to the 19th century, and we have to thank the unfavourable

reception of his last novel for his decision to return to his first

love, poetry. So the poet turned novelist went on to become a novelist

turned poet, and this reinvention, as we would call it today, of himself

was to have a marked influence on the content and style of his poetry.

In Hardy’s greatest novels, “Tess of the d’Ubervilles” and “Jude the

Obscure”, the struggles of the eponymous protagonists for

self-fulfilment end in tragedy. This is shown to be due to the

indifference of whatever higher powers there might be, allowing them to

fall victim to cruel twists of circumstance, hostile social forces and

their own “tragic flaws”.

This unrelievedly pessimistic view of life is reflected in Hardy’s

poetry, even though he argues that “what is alleged to be ‘pessimism’

is, in truth, only such ‘questionings’ in the exploration of reality”,

and again, in another poetic preface, that “a true philosophy of life

seems to lie in humbly regarding diverse readings of its phenomena as

they are forced upon us by chance or change.”

|

|

Thomas

Hardy |

Such questionings of what he calls “life’s little ironies” and

readings of its phenomena constitute much of the subject matter of his

poetry. As the first two lines of a poem of his puts it, “Any little old

song will do for me”, and “A Meeting with Despair” is a good example.

These are the first two verses:

“As evening shaped I found me on a moor Which sight could scace

sustain: The black lean land, of featureless contour, Was like a tract

in pain.

“This scene, like my own life,” I said, “is one Where many glooms

abide; Toned by its fortune to a deadly dun-Lightless on every side.”

This extract is revealing of the influence of the novelist on the

poet. The style is descriptively narrative, landscape plays a major role

in determining context and atmosphere, and the mood is joyless. The

versification is conventional, but the effective containment of the

prosaic phraseology imparts liveliness to the rhythm and the touches of

alliteration and assonance are effective. Yet we can see that the poem

might have benefited from more than the maximum of three or four drafts

that Hardy said he allowed himself to make of his poems so as to

maintain their freshness.

Despite the negative nature of his “philosophy of life”, Hardy has

definite positive centres that feature in, and heighten the appeal of,

his better verse. They are his love for the “Wessex” countryside of his

own naming, his affection for its simple inhabitants and his sympathy

for its animal and bird life.

These motivations enhance his powers of observation and description

and enable him to create some positive value for himself and his

readers. “The Darkling Thrush” begins desolately enough, detailing a

deathly bleak winter scene. All at once the poet hears a joyful

“full-hearted evensong” from “an aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume, (that) Had chosen thus to fling his soul Upon

the growing gloom.”

This is one of the special moments of poetry, reminiscent of Keats

hearing the nightingale and Hopkins sighting the windhover. What makes

it especially poignant is the frailty of the bird that produces “such

ecstatic sound” amid “so little cause for carollings”. The concluding

lines are heartrending on account not only of the bird but of the poet

whom the bird somewhat symbolises: “That I could think there trembled

through His happy good-night air Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew And

I was unaware.”

“Afterwards” is another moving poem. It is anchored midway in the

lines: “One may say, ‘He strove that such innocent creatures should come

to no harm, But he could do little for them; and now he is gone.’ ” The

poet’s (and every caring person’s) love for the natural world and its

creatures is seen to have an enduring value in spite of his transience

and his limited ability to act on their behalf...

Yet, the undoubtedly magnetic quality of such poems is primarily by

way of reflecting on experience from a given viewpoint or philosophy. We

sense that something is wanting that makes for the greatest poetry, and

this is the full emotional impact arising from a poet’s personal

involvement in his experience.

Something was needed to provide this and it came, like a bolt of

lightning, with the death of Hardy’s first wife (he remarried a couple

of years later) from whom he had long been estranged.

Hardy was powerfully affected by this. He revisited the scenes of

their courtship and early married life in Cornwall as if to recover what

had now for ever been lost. The result was some of the greatest love

poems ever written, a mere dozen or so, on which Hardy’s reputation as a

great poet chiefly rests.

“Woman much missed, how you call to me, call to me, Saying that now

you are not as you were When you had changed from the one who was all to

me, But as at first, when our day was fair.

“Can it be you that I hear? Let me view you, then, Standing as when I

drew near to the town Where you would wait for me: yes, as I knew you

then, Even to the original air-blue gown!

“Or is it only the breeze in its listlessness Travelling across the

wet mead to me here, You being ever dissolved to wan wistlessness, Heard

no more again far or near?

“Thus I; faltering forward, Leaves around me falling, Wind oozing

thin through the thorn from norward, And the woman calling.”

This one example, “The Voice” in its entirety, suffices to show the

transformation wrought in the poetic sensibility by intensely felt

experience and in poetic expression through its recreation. Bereavement

has touched off not the usual pain of separation, but the painful

realisation of what the failure of a relationship has cost over the

years. This is communicated through the skilful juxtaposition of a

vision of the past with a landscape of the present and verse that has

the clarity of good prose and the evocativeness of good poetry. Among

other poems in this key group are “The Self-Unseeing” and “After a

Journey”.

Thus the aged poet is finally swept off his feet by the rediscovery

of love. The tragedy of this love is that it has, in the words of

Marvell, “been begotten by despair upon impossibility.” It is impossible

of fulfilment even in the memory, unlike U Karunatilake’s Kundasale love

poems where the poet is able to come to terms with the desolation of

bereavement through the recollection of a joyful relationship.

In Hardy’s case, the experience of desolation is complete, the

pessimism finally has a genuinely personal reason for its being

unrelievable, and he can rightly be viewed, therefore, as a tragic poet. |