Expansion of university education and graduate unemployment

Prof. Gamini Samaranayake - Chairman University

Grants Commission

The paper is divided into five major sections. The first part

examines the origin, development and present status of university

education in Sri Lanka. The second part deals with the profile of

graduate unemployment, the third part examines the causes of graduate

unemployment, the fourth part examines graduate employability, and the

responses of the government to graduate unemployment, the fifth part

deals with the knowledge hub, advantages, opportunities and challenges,

while the final part of the paper deals with the observations and

suggestions. The paper is divided into five major sections. The first part

examines the origin, development and present status of university

education in Sri Lanka. The second part deals with the profile of

graduate unemployment, the third part examines the causes of graduate

unemployment, the fourth part examines graduate employability, and the

responses of the government to graduate unemployment, the fifth part

deals with the knowledge hub, advantages, opportunities and challenges,

while the final part of the paper deals with the observations and

suggestions.

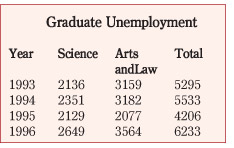

Source: University Grants Commission

It is generally assumed, that there were 25,000 unemployed graduates

in 1998.

It is evident that more arts graduates were unemployed than graduates

from other disciplines and this trend continues.

Gender disagregated information indicates that female graduates have

higher unemployment rates than their male counterparts.

In 1971, out of 3,898 unemployed graduates 2338 were females which

indicate that 60 percent of the unemployed graduates were females. In

1989/91 out of 4,798 unemployed graduates 3,069 were female while in

1985 and 86 out of 5420 unemployed graduates 3417 were female. This

shows a feminization of graduate unemployment.

In analyzing the perceptions and attitudes of male and female

graduates some significant variations were noted. In terms of job

preference unemployed female university graduates prefer school teaching

than government administrative jobs or private sector managerial jobs.

Male university graduates prefer government administrative jobs than

teaching or private sector managerial jobs. In analyzing the perceptions and attitudes of male and female

graduates some significant variations were noted. In terms of job

preference unemployed female university graduates prefer school teaching

than government administrative jobs or private sector managerial jobs.

Male university graduates prefer government administrative jobs than

teaching or private sector managerial jobs.

However, males and females prefer to work in the public sector than

in the private or NGO sector. Moreover, more female graduates are

reluctant to work in the private sector than their male counterparts.

Graduates on the whole are reluctant to set up self-employment schemes

and believed that the government should provide them with jobs.

The preference of female graduates for the teaching profession could

be based on the fact that it is a profession with five to six hours of

work coupled with three months of school holidays which permits women to

balance their productive and reproductive roles.

Underemployment is a significant aspect of graduate unemployment

which often remains unrecognized and is seldom analyzed as an issue.

Unlike unemployment, underemployment eludes definition and assessment.

It can be described generally as a situation in which a person is forced

to accept employment below his or her educational level. It

predominantly affects the social science graduates.

Definite statistics on underemployment are not available, but are

identified on the basis of low earnings. Around 14,000 graduates were

employed in the work force after 1970, but 80 percent of them received

salaries between Rs. 200 to 300 per month, which placed them below the

poverty line. Definite statistics on underemployment are not available, but are

identified on the basis of low earnings. Around 14,000 graduates were

employed in the work force after 1970, but 80 percent of them received

salaries between Rs. 200 to 300 per month, which placed them below the

poverty line.

Graduates who were employed under schemes on the eve of the General

Election in 1994 received a monthly salary of Rs. 2500. It is the salary

received by a worker in a garment factory. Due to limitations in job

opportunities, in the public as well as the private sector and

widespread underemployment the real value of university education has

eroded.

In this context, unemployment and underemployment is not the sole

problem: the means of securing employment is another aspect of the

problem of graduate unemployment in the country. There are three main

avenues used to obtain employment. The first is applications for jobs in

response to advertisements. The second is the assistance of family

members and/or friends and the last but not least the assistance of

politicians.

During the colonial period there was a trend towards white collar

employment on the basis of one’s family and personal contacts. This

system of obtaining employment enabled the students belonging to

families with influence to secure stable jobs, while the students in the

rural sector who invariably belonged to the peasant families were at a

grave disadvantage.

Currently, the most prevailing avenue has been assistance of the

government in power either voluntarily or through pressure of agitation.

Causes of graduate unemployment

To a certain extent we should also recognize that employment

opportunities for graduates are highly dependent on the economic growth

of the country. The slow rate of economic growth and the allied problem

of providing increased economic opportunities for the growing numbers

entering the labour market led to a high level of unemployment among

graduates especially from the social sciences and humanities. Apart from

national economic issues, there are a number of causes which have been

identified as contributory factors to the origin and development of

graduate unemployment.

Of these an ad hoc expansion of the universities and student

population, the nature of the courses, and quality of the graduates is

noteworthy.

Since these factors are related to the expansion of higher education

in Sri Lanka, it is necessary to examine the context of the development

of university education. Since these factors are related to the expansion of higher education

in Sri Lanka, it is necessary to examine the context of the development

of university education.

The University College that was established in 1921 expanded to the

University of Ceylon by 1942. The university had only four faculties,

and a limited number of students offering for the degree of BA, BSc and

MBBS.

However, the entrance of students was limited compared to the

enrollment of students in primary and secondary education upto the early

1960s. There were 904 students in 1942, 1294, in 1947 and 48 and 2471 in

1956 and 7. The language of instruction was English and its students

were drawn from the English speaking urban middle class.

It was fashioned essentially on the Ox-Bridge model, and the

curriculum, the teaching learning process and examinations of the

university followed the pattern of British Universities. It was exactly

the model of elite education.

However, university education underwent many changes especially with

the granting of universal franchise in 1931, free education in 1945, the

political changes in 1956 and the introduction of university education

in Sinhala and Tamil Languages in 1959. It marked the beginning of the

inclusion of students from a wide ranging socio-economic background.

Consequently, the number of universities increased from one in 1942 to

three in 1960. Two of these new universities Vidyodaya (Kelaniya) and

Vidyalankaraya (Sri Jayewardenepura) were Buddhist pirivenas (monastic

institutions) which were elevated to the status of universities.

To accommodate an increased demand of university education ad hoc

measures were taken by the government such as elevating three affiliated

colleges as Universities namely Rajarata, Wayamba and Sabaragamuwa. By

1970 the number of universities increased to five and by 1978 there were

seven universities in the country. The rest were established after 1994.

The number of students entering higher education thus increased from

1612 in 1948, to 5000 in 1959, to about 14,000 in 1970 and 17,449

student enrolments in 1978. By 1988 and 89 there were 29,781 students

internally in university education.

At present, 80,000 students are in universities. Annually about

13,000 internal graduates pass out from universities and more than 50

percent of them are from the Arts and management streams. At present, 80,000 students are in universities. Annually about

13,000 internal graduates pass out from universities and more than 50

percent of them are from the Arts and management streams.

The output of external graduates is around 6,500 and the Open

University too has an output of about 500 per year. Thirty years ago 70

percent of the student population was admitted to the faculties of

Social Sciences and Humanities.

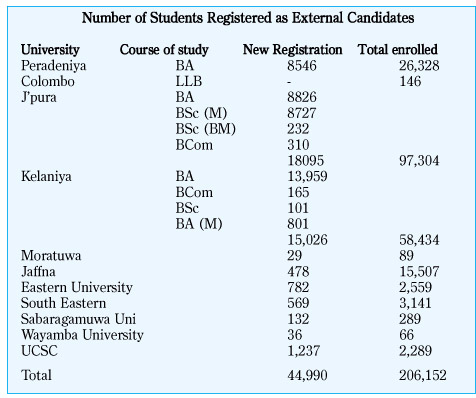

In addition, since 1962, there has been a system of external

examinations in university education and almost 200,000 students are

registered with the eleven universities in the country. Table 2 shows

the number of students and courses offered by the external students

registered with our universities.

Not only did the number of students and institutions dealing with

higher education expand but the socio-economic composition of the

student population and the quality of education, too changed over the

years.

The most significant feature of this rapid growth is the changing

socio-economic composition of the student population in the period 1959

up to date.

There are a few systematic studies on the socio-economic background

of the student population mainly by Murray A. Strauss in 1950, and J E

Jayasooriya in 1965.

These students mainly belong to the urban middle class social

background. Moreover, they had no anxiety about their own future

because, after graduation, they were assured of employment in the higher

echelons of government or the private sector.

This trend began to change in the mid 1960s. Since then a substantial

proportion of students tended to come from the lower middle class, the

working class and the peasant class.

The concentration of students from such social backgrounds is the

strongest in the faculties of Arts, Social Sciences, Humanities and

Commerce and Management.

Besides, a majority of the university students are by ethnicity

Sinhala, by religion Buddhist and are from the rural sector. This trend

further developed as a result of the “standardization”, and “district

quota system” introduced in 1973. Besides, a majority of the university students are by ethnicity

Sinhala, by religion Buddhist and are from the rural sector. This trend

further developed as a result of the “standardization”, and “district

quota system” introduced in 1973.

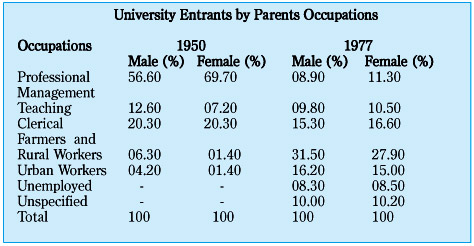

According to the University Grants Commission (UGC) Statistical Hand

Book of 1988/89, the occupational background of the parents of the

students admitted in the academic year belonged to the low-income

category.

Nearly 40 percent of the parents of the students earned a monthly

income of less than Rs. 1000. As given in Table 3 an analysis of the

University Entrants by parents Occupation for the Academic Year 1950 and

1977 shows the changing socio-economic background of the student

population.

According to this analysis there is a decline in the number of

students whose parents have a professional or managerial background

while there is an increase in the number of students whose parents are

small farmers or rural workers.

In spite of the increasing number of universities and the number of

students the curriculum, the teaching learning process, and the

relevance and quality of education remained unchanged.

A sample survey based on the student population at the University of

Peradeniya indicated that 62 percent of students are disappointed of the

highly theoretical lectures, lack of practical exposure to industry,

lack of industrial training, poor teaching techniques, lack of

application of education technology in teaching, and poor relations with

the private sector.

The expansion of the student population, the introduction of

Suwabasha education at university level and the changing socio-economic

composition of the student population changed the education system from

an elitist to a mass system.

An elitist system emulates the western model of education with a

strong western philosophical bias. The students who undergo the elitist

system of education expect to be assimilated to the elite circles and

are therefore guided to conform.

Students in the mass system are more prone to political activities,

and are less likely to align with the political elite. Thus, the

transition of university education from an elitist to a mass resulted in

a high level of political dynamism among the student population.

Source: G Samaranayake, 1992 p16

The universities in Sri Lanka depend solely on the state for funds.

However, the budgetary allocations for higher education over the years

failed to meet the demands of the expansion in the system leading to a

concomitant reduction in facilities.

The lack of qualitative improvement in university education has been

a major manifestation of the lack of financial resources made available

for tertiary education. From 1959 to 1966 and 67, the total real

expenditure on university education rose by only 27 percent while the

student enrolment had increased as much as 278 percent or tenfold.

The available statistics indicate that government expenditure on

university education is 1.4 percent of government expenses and 0.34

percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). One can conclude,

therefore, that university education has been provided for a

significantly larger number with very little increase in the total

resources diverted to it, thereby reducing its quality to a great

extent. The available statistics indicate that government expenditure on

university education is 1.4 percent of government expenses and 0.34

percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). One can conclude,

therefore, that university education has been provided for a

significantly larger number with very little increase in the total

resources diverted to it, thereby reducing its quality to a great

extent.

Furthermore, the problem of graduate unemployment has increased due

to limitations in the expansion of the State sector as a result of

economic liberalization, structural changes and privatization of

cooperation’s and other public ventures.

Graduates who have studied Commerce and Management Subjects are more

open to the prospects of working in the private sector than Social

Science graduates.

Graduates are unable to secure employment in the private sector

mainly due to the mismatch between the skills of the Social Science

graduates and the needs of the private sector which has expanded during

the past decades,

One of the main criticisms aimed at university education including

the Central Bank Report of Sri Lanka for 2009 is that higher education

is of “low quality and low standards and that 32 percent of students

admitted to national universities study social sciences and humanities

and a substantial proportion of these graduates find it difficult to

obtain productive employment.

The same report concludes that “the country has a supply driven

education system with little relevance to labour market conditions and

to entrepreneurial culture”.

However, graduate unemployment is not purely a university problem but

universities have a responsibility and accountability to extend all

their support to solve the problem.

Graduate employability

Currently at global level universities are very much concerned with

graduate employability as a means of overcoming the problem of graduate

employment. As an acceptable definition of employability, the best I

could find stated that “employability is a set of achievements,

understanding and personal attributes that make an individual more

likely to gain employment and be successful in their chosen occupations,

which benefit themselves, the workforce, the community and the economy”.

Employability thus defined has wider interpretations and connotation

especially for a developing country like Sri Lanka grappling with issues

of political violence, poverty and rehabilitation arising from manmade

and natural disasters.

A survey conducted by the Chamber of Commerce in Sri Lanka in 1999

has mentioned that the following attributes are expected by the private

sector employers from the graduates in addition to their academic

qualifications.

They are as follows: ability for effective communication skills along

with English; ability of interpersonal relationships, ability of leading

a team and getting the results within a short time; ability of

prioritization of work; initiation of work and intention of its

development; open, proactive and pragmatic mind; computer literacy,

ability of logical and rational thinking, general knowledge and personal

hygiene, office and social etiquette.

A similar study conducted by the Council for Industry and Higher

Education in the United Kingdom (UK) in 2008 found that employers rate

communication skills, team work, integrity and intellectual ability over

literacy and numeracy.

It is suggested that students are provided with opportunities to

access and develop everything on the lower tier of the model such as

career development learning; Experience (work and life); Degree subject

knowledge, understanding and skills; Generic skills and Emotional

Intelligence; and essentially opportunities to reflect and evaluate

these experiences, which will result in the development of higher levels

of self-efficacy, self-confidence and self-esteem- the crucial links to

graduate employability.

The above mentioned study and survey confirms that employers prefer

social skills and personality type as more important than the degree

qualifications to meet the demands of a market driven and knowledge

based economy. This study also found that the services delivered by the

university careers advisory services to be unsatisfactory.

In developing the strategic plan for the UGC for the years 2008-2012

we analyzed these issues in some depth. We were surprised to learn that

none of the donors, policy makers and planners had conducted a

comprehensive study of the needs of employers such as the study done in

the UK.

The universities in the UK are also striving to address issues of

employability as evidenced in their websites such as the University of

Hull and Wolverhamption.

This is a gap that we in Sri Lanka need to fill to fully understand

the employability of our graduates and the mismatch between the

requirements of the employers and the education provided by the higher

education system. The Ministry of Higher Education and the UGC has

expanded IT facilities at our universities, introduced a system of

lateral entry, revised the curricular and introduced new courses,

placement years in collaboration with the private and public sector and

established a system of career counselling in universities.

However, more in-depth analysis is needed on the current skills of

our students, the needs of employers both in the private and public

sector and the recruitment patterns and policies of employers for us to

fully understand the issue of employability.

However, it is my contention that we need to consider some critical

factors that are confined to our higher education system as well as our

country context.

One of the main factors is that the universities cannot impart

critical skills such as problem solving, analytical thinking and

interpersonal skills required for employability within the three or four

years that students spend at the university. Students need to acquire

these skills through a Good Early Childhood Care and Development

Programme that is regulated, has quality standards of reference and a

sound system of assessment.

The formal education system needs to follow up with a well

constructed curriculum that is implemented effectively across the

country. The component titled preparing for the “ world of work” was

introduced recently to secondary education but its implementation

remained varied and poor. Therefore, the education system from ECCD to

secondary education needs to be aligned to the basic objectives of

increasing the skills of children. The universities can assign higher

priority to imparting language and IT skills so that meaningful changes

can be made in the higher education system concomitantly.

The second factor derives from our country context. What is the

reality in our universities? Any form of change is resisted with

political overtones and the policy makers and administrators are

challenged every step of the way in bringing about changes in the

system.

This subculture is manifest in the high degree of politicization in

the universities which are currently the base for insurrectionary

politics as exemplified by the violence in universities whether it is

political factionalism or “violent ragging”. This subculture of violence

resists any form of change and the silent majority is penalized by a

violent few.

The third factor is that employers in the private sector and employer

groups keep saying that universities need to do more to improve graduate

employability. But employers too need to contribute their share by

working more closely with the universities, the UGC and the Ministry of

Higher Education to develop a system of identifying the skills young

graduates need to prepare them for the world of work.

Currently, a few universities are trying to address the issue of

graduate employability strategically. However, these universities need

both financial and human resources to diversify and increase

employability.

We also need to train our academic staff, to invite professionals

from the private sector to teach at our universities and expand

opportunities for graduate students to acquire skills.

Government’s response

In this context, it is necessary to examine the measures taken by the

government to solve or contain the problem of graduate unemployment in

the country. Since 1970, governments have introduced a special

employment programme for graduates.

The government has recruited graduates as teachers, development

officers and trainees in the graduate scheme in order to ease the

problem of unemployment.

The government from 1970-77, found it necessary to address this

problem and as a result introduced the system of appointing a political

authority for each district. The political authority was a Member of

Parliament belonging to the political party in Office.

The system further stipulated that a person seeking a job had to

obtain a letter of recommendation from the political authority. This

represented a form of patron-client relationship and proved to be a

barrier hampering those supporting any Opposition political party from

securing employment.

The UNP government which came to power since 1977 introduced the

system of a “job bank”. This system also created ways and means of

practicing corrupt practices such as bribery. The lack of personal

contacts, political or bureaucratic patronage and corrupt practices in

securing employment has posed additional barriers to graduates seeking

employment.

However, the state has found it increasingly difficult to absorb

graduates into the shrinking ranks of the public sector. Successive

governments have been compelled to seek the assistance of the private

sector to solve the problem of unemployment among graduates. Since the

early 1990s, the government has set up a scheme for graduate trainees

within the private sector.

The Programme offers two-three years of training in private companies

at a monthly allowance of Rs. 1500. There is to be no guarantee of

placement at the end of the training.

However, nearly 9000 applications have been processed for this

programme.

Prior to the General Election of August 1994, the government opened a

trainee scheme for unemployed graduates, which absorbed a majority of

the unemployed graduates at that time.

In 1997, the government inaugurated a new scheme called the Tharuna

Aruna with the private sector to address the same issue. The main

objective of the programme was to develop the knowledge, skills and

attitudes of unemployed graduates in order to enable them to secure

employment in the private sector. Under this scheme placements have been

offered to 1130 graduate trainees in 345 companies during the period

1997-1998.

In 2004 about 42,000 graduates were absorbed as teachers and office

workers. However, a majority of them do not have any promotion scheme or

career path and are still underutilized.

The Higher Education Ministry has embarked on several programmes and

initiatives to mitigate the problems of unemployed graduates. These

initiatives among others are the introduction of skills modules to

increase communication skills, leadership and team building into the

students’ pre-orientation programme, basic entrepreneurship modules,

industrial training programmes, and collaborative programmes with

relevant professional bodies.

Various measures have been initiated by the UGC and universities to

enhance graduate employability over the last few years. Carrier Guidance

Units are established in each and every university under the supervision

of the Standing Committee of the UGC. While increasing the number of

university admissions into Science oriented faculties the intake to Arts

courses in Universities has remained relatively static at around 5,000

students.

Steps have been taken to improve the quality of the degree programme

on the basis of international bench marks. During the last few years,

the Higher Education Ministry together with the UGC worked on Improving

Relevance and Quality of Undergraduate Education (IRQUE) a project

designed from a loan given by the World Bank to improve the quality of

university education.

Furthermore, the medium of instruction has shifted from Sinhala and

Tamil to English. Universities need to do tracer studies before

convocations are held each year. The tracer study on graduate

employability has shown significant improvement on the marketability of

graduates in some universities.

A recent survey on Graduates of the University of Colombo has

revealed that more than 55 percent of Science and Management graduates

have found employment during three months after graduation while 12

percent and 16 percent of Arts and Education graduates respectively have

found employment. A similar study done by the Moratuwa University too

has revealed that more than 95 percent of the graduates of the Moratuwa

University that are qualified in the fields of Engineering and

Architecture have found employment within six months of their

graduation.

The prevailing idea is that it is the duty of the government to find

a solution to the problem of graduate unemployment. Although, the

government has emphasized the expansion of the private sector as a

solution to graduate unemployment, the graduates themselves are not

willing to join the private sector as it is a competitive field where

job security depends on performance.

The private sector on the other hand prefers proficiency in English,

personality and social standing. Although the Sri Lankan education

system produces a limited amount of human resources for Science and

Technology, the industrial sector is not capable of absorbing all of the

graduates from the disciplines of Science and Technology.

Many such graduates leave the country for foreign employment while

some are employed in non-technical disciplines indicating the lack of a

concomitant expansion in industry to absorb the Science and Technology

graduates. The private sector and the state sector needs to reconfigure

its recruitment, induction, training, mentoring and coaching system.

I have found that our graduates have the latent skills and capacity

to compete in the labour market but the employers themselves lack the

creativity, innovativeness, and capacity to develop a system of

recruitment, capacity building and coaching and mentoring young

graduates.

The solution can be found on a short-term as well as long-term basis.

The short-term strategies are for the government to invest in training

the unemployed graduates to acquire the competencies needed for the

modern work place and develop systems to link them to the world of work.

The long term solution lies with all of the stakeholders of higher

education: the government, private sector employers, universities and

university students.

The university educational system has to be re-oriented to meet the

challenges of graduate unemployment. The existing teaching and learning

process relies heavily on rote learning.

Traditionally, students are passive listeners, and they rarely

challenge each other or their professors in classes. Teaching focuses on

the mastery of content, not on the development of the capacity for

independent and critical thinking. Knowledge, skills and talent will be

crucial factors for growth in the future, while innovation and

willingness to change will be a driving force.

The university system needs to be re-structured, concerned with

quality and relevance, and introduce job-oriented programmes. Therefore,

the Ministry of Higher Education and the UGC plans to address issues

through long-term plans of change. Establishing Sri Lanka as a knowledge

hub in South Asia is one such option that is being explored.

Knowledge hub

A Knowledge Hub is broadly defined as a designated region intended to

attract foreign investment, retain local students, build a regional

reputation by providing access to high-quality education and training

for both international and domestic students, and create a

knowledge-based economy.

A knowledge hub is concerned with the process of building up a

country’s capacity to better integrate it with the world’s increasing

knowledge based economy, while simultaneously exploring policy options

that have the potential to enhance economic growth. An education hub can

include different combinations of domestic and international

institutions, branch campuses, and foreign partnership, within the

region. The main functions of hubs are to generate, apply, transfer, and

disseminate knowledge.

The concept of a knowledge hub for Sri Lanka was proposed by

President Mahinda Rajapaksa through his policy document during the

presidential election in 2009. It is stated that Sri Lanka will “develop

youth who can see the world over the horizon”. “We have the opportunity

to make this country a knowledge hub within the South Asia region. I

will develop and implement an operational plan to make this country a

local and international training centre for knowledge”.

The Higher Education Ministry is grappling with the empirical

implications of translating this promise into reality. The Ministry has

invited foreign universities to set up campuses to provide a more

diversified higher Education programme to increase access for local

students and to attract students from overseas to study in Sri Lanka.

Just as in Singapore Sri Lanka’s strategy is to piggy- back on

internationally renowned universities so that the process is cost

effective and mutually beneficial.

Furthermore, it is planned that 10 branch campuses of “world class”

universities would be established by 2013. The Knowledge Hub Agenda has

given greater prominence especially to the fields of Science and

Technology, Information and Communication Technology, Skills

Development, and Research and Development in Applied Sciences.

Advantages

Sri Lanka enjoys several advantages to develop into an education hub.

First, of all the ever increasing demand for higher education in the

country is an impetus for growth and advancement. Annually, well over

250,000 students sit for the Advanced Level Examination and half of them

are qualified for university education. However, only 22,000 are able to

enter university education in the country.

Of them, 9000 enroll in vocational training through 12 Advanced

Technological Institutes, 20,000 enroll at the Open University, 8000,

access overseas education, 20,000 register as external candidates while

9000 are studying for a foreign degree via cross border institutes.

Nearly, 60,000 students are looking for alternative higher education

locally.

To be continued |