The new poor

After training, still scrambling for employment:

Peter S. Goodman

In what was beginning to feel like a previous life, Israel Valle had

earned $18 an hour as an executive assistant to a designer at a

prominent fashion label. Now, he was jobless and struggling to find

work. He decided to invest in upgrading his skills.

The New Poor

It was February 2009, and the city work force center in Downtown

Brooklyn was jammed with hundreds of people hungry for paychecks. His

caseworker urged him to take advantage of classes financed by the

federal government, which had increased money for job training. Upgrade

your skills, she counseled. Then she could arrange job interviews.

|

Training to get to a higher position |

For six weeks, Valle, 49, absorbed instruction in spreadsheets and

word processing. He tinkered with his resume. But the interviews his

caseworker eventually arranged were for low-wage jobs, and they were

mobbed by desperate applicants. More than a year later, Valle remains

among the record 6.8 million Americans who have been officially jobless

for six months or longer. He recently applied for welfare benefits.

“Training was fruitless,” he said. “I’m not seeing the benefits.

Training for what? No one’s hiring.”

Hundreds of thousands of Americans have enrolled in federally

financed training programs in recent years, only to remain out of work.

That has intensified skepticism about training as a cure for

unemployment.

Even before the recession created the bleakest job market in more

than a quarter-century, job training was already producing disappointing

results. A study conducted for the Labour Department tracking the

experience of 160,000 laid-off workers in 12 states from mid-2003 to

mid-2005 -a time of economic expansion, found that those who went

through training wound up earning little more than those who did not,

even three and four years later.

“Over all, it appears possible that ultimate gains from participation

are small or nonexistent,” the study concluded. In the last 18 months,

the Obama administration has embraced more promising approaches to

training focused on faster-growing areas like renewable energy and

health care. But most money has been directed at the same sorts of

programs that in past years have largely failed to steer laid-off

workers toward new careers, say experts, and now the number of job

openings is vastly outnumbered by people out of work. “It’s such an ugly

situation that job training can’t solve it,” said Ross Eisenbrey, a job

training expert at the Economic Policy Institute, a labour-oriented

research institution in Washington, and a former commissioner of the

federal Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission.

“When you have five people unemployed for every vacancy, you can

train all the people you want and unfortunately only one-fifth of the

people will get hired. Training doesn’t create jobs.”

Labour economists and work force development experts say the

frustration that frequently results from job training reflects the

dubious quality of many programs. Most last only a few months, providing

general skills without conferring useful credentials in specialized

fields.

Programs rarely involve potential employers and are typically too

modest to enable cast-off workers to begin new careers. Most job

training is financed through the federal Workforce Investment Act, which

was written in 1998 - a time when hiring was extraordinarily robust.

Then, simply teaching jobless people how to use computers and write

resumes put them on a path to paychecks. Today, even highly skilled

people with job experience of two decades or more languish among the

unemployed. Whole industries are being scaled down by automation, the

shifting of work overseas and the recession.

|

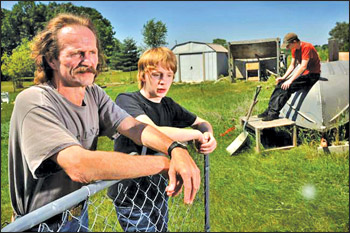

In Minnesota, David Gustafson was trained to program machinery:

Just as soon as I could say, “Yes, I can program,” I got a job.” |

“A lot of the training programs that we have in this country were

designed for a kind of quick turnaround economy, as opposed to the

entrenched structural challenges of today,” said Carl E. Van Horn, a

labour economist and director of the John J. Heldrich Center for

Workforce Development at Rutgers University.

“It’s like attacking a mountain with a toothpick. You take a policy

that was designed for the best economy that we had since World War II

and you lay it up against the economy that is the worst since World War

II. It can’t work.”

Claiming successes

The Obama administration argues that expanded job training has

already delivered success. As part of the nearly $800 billion stimulus

package begun last year, the administration increased grants sent to

states for training programs devoted to laid-off workers by $1.4 billion

for 2009 and 2010.

Those funds came on top of $2.9 billion allocated through normal

budget channels for grants in those two years. Last year, the number of

laid-off workers in job training reached 241,000, up from about 124,000

the year before, according to the Labour Department.

“These programs are really working,” said the assistant secretary of

labour, Jane Oates. “These are folks who clearly want to go back to work

and we’re able to help them get back to work. The investment in job

training is one that’s not only going to pay off in the short term, it’s

going to help us be more competitive in the long term.”

According to the Labour Department, 85 percent of laid-off workers

who received training in 2007 and 2008 gained jobs within a year of

completion. But the department does not track what percentage of them

gained jobs in their fields of study and so far lacks any data for 2009,

the first year of the Obama administration’s expansion.

In Minnesota, David Gustafson was trained to program machinery: “Just

as soon as I could say, ‘Yes, I can program,’ I got a job.”

Articles in this series are examining the struggle to recover from

the widespread strains of the Great Recession. Experts harbor doubts

about the reliability of Labour Department numbers, which are derived

from reports by state agencies that collect data from community colleges

and employment offices whose training funds are dependent upon reaching

benchmarks.

Twice the Labour Department had to correct the data it supplied for

this article. “The states play all sorts of games,” said Eisenbrey, from

the Economic Policy Institute.

Signs of Progress

But those who oversee job training say results have improved

significantly in recent years. “We’ve come a long way,” said Robert W.

Walsh, commissioner of the New York City Department of Small Business

Services, which oversees the Workforce1 career centers, including the

Brooklyn office where Valle enrolled. “We’re now focused on where the

jobs are and the track records of the providers.”

Those factors are crucial, say advocates for expanded training, who

point out that even with near double-digit unemployment, some jobs lie

vacant, awaiting workers with adequate skills.

“There’s plenty of jobs in health care, in technology,” said Fred

Dedrick, executive director of the National Fund for Workforce

Solutions, which advocates for increased and improved job training.

“Once people move up, that creates opportunities for other workers.”

There is some evidence that this approach works. Two years after

completing programs tied directly to the needs of local industries

suffering shortages of skilled workers in the South Bronx, Boston and

Milwaukee, graduates were earning 29 percent more than similar workers

who did not receive training, according to a new survey from

Public/Private Ventures, a nonprofit group that advocates for expanded

job training.

A widely admired program begun in Michigan in 2007, No Worker Left

Behind, provides up to $10,000 over two years for laid-off and

underemployed workers who pursue certificates and degrees in areas of

significant growth. The program has trained technicians to work on major

energy storage projects and aircraft mechanics to service engines at

commercial operations that have taken over former Air Force bases.

“We need to know that we’re training people in an in-demand growth

area today,” said Andrew S. Levin, who oversees the Michigan program.

But forecasting where jobs will be can be tricky. Among those completing

training by the end of 2009, 41 percent were still looking for work as

of June, according to Michigan data.

Nationally, prospective trainees are often steered into programs by

counselors at community colleges and employment centers who lack

awareness about which industries are hiring.

In the suburbs of Philadelphia, Eric Nelson left a job at a credit

union call center in late 2004 to enroll at a state college. There, the

career services department helped him choose a course of study by

consulting job growth projections. The result led to geographic

information systems -the mapping of data by place.

“It seemed like the thing to do,” Nelson recalled, adding that he was

assured he would easily land an entry-level job paying $35,000 a year.

But when Nelson, 42, graduated with his bachelor’s degree in May 2008,

facing nearly $50,000 in student loan debt, he was horrified to discover

that graduates greatly outnumbered jobs. Only people with six or seven

years’ experience were getting hired, he said.

“I’ve had no offers at all,” he said. He is now living off his wife’s

wages as a librarian and contributions from his parents. Even programs

with successful track records tend to be focused on people who are

easier to employ - those with substantial skills and experience. In late

2007, in the Minneapolis suburbs, Hennepin Technical College joined with

local employers to help workers laid off from area factories secure new

jobs.

More skills, better luck

The Minneapolis-St. Paul area exemplifies how unemployment reflects

not only a shortage of jobs but also a mismatch between jobs and skills.

A half-century ago, mainframe computers were assembled in the area,

before the business shifted to Silicon Valley. But large-scale

manufacturing remains, particularly in one fast-growing industry whose

jobs seem unlikely to be shifted overseas: medical devices.

The New York Times |