Counter terrorism

From a human rights perspective:

Lionel Wijesiri

Terrorism: frightening in its

unpredictability, unsettling by its seemingly random nature - its

capacity to strike apparently anywhere, anytime, anyone. We, in Sri

Lanka, had tragic experience with terrorism for 30 years, dating from

the 1980’s to 2010. Today, in the climate of democratic consolidation,

we have shown ourselves determined to protect our hard-won sovereignty

by opposing all forms of terrorism, wherever they may appear, and have

understood that this can only be done with the strong support of all our

people

All around us, from Africa to Asia, and from America’s 9/11 to

Spain’s and Europe’s 3/11, the price of terrorism has been abject and

unjustifiable suffering. Terrorism in all its forms and manifestations

constitutes one of the most serious threats to global peace and

stability. The UN Security Council in Resolution 1269 called upon all

states to cooperate with one another, to prevent and suppress terrorist

acts, to protect their nationals and other persons against terrorist

attacks, and to bring to justice the perpetrators of such acts. At the

same time, however, UNO also states that countries must ensure any

measures they take to combat terrorism comply with their obligations

under international law, in particular international human rights and

humanitarian law. In essence, the point is that the fight against

terrorism has to be fought within the boundaries of human rights.

|

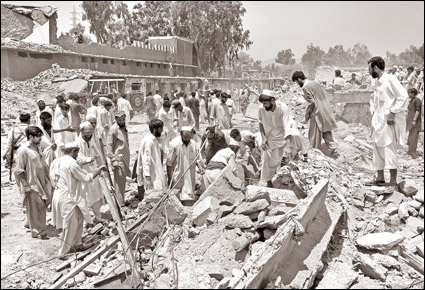

Residents search for blast victims in the rubble following a

suicide bomb attack in the district of Mohmand. AFP |

This theory leaves us with three important questions to explore.

First, to what extent can the fight against terrorism be considered a

fight for the full enjoyment of human rights? Second, do human rights

prevent us from countering terrorism effectively? How are we to strike

the right balance? Thirdly, to what extent does our strategy to counter

terrorism require us to actively promote human rights? These are

difficult questions to answer. There are no easy answers.

It is in this context the recent speech by Dr. Palitha Kohona, our

permanent representative in the UN, becomes relevant. Two paragraphs of

his speech are quoted: “The normative framework on civilian protection

cannot be applied in a theoretical manner regardless of the

circumstances.

Our own past experience in dealing with a terrorist group that used

the civilian population forcibly as a human shield to launch attacks on

the armed forces should remind all of us of the challenges. While

shielding behind innocent civilians they also succeeded in marshalling

the support of their sympathizers abroad to stage massive

demonstrations. Unfortunately, too many well meaning persons were taken

up by these cynical efforts to garner sympathy. Much of the rules of war

are based on the presumption that the parties to the conflict are

conventional armies of responsible States but terrorists totally

disregard these laws and principles”.

“The cost of armed conflict on civilians and the need for

accountability is a matter of concern to all democratic and elected

Governments including our Government. In this context, our Government.

established a Commission of Inquiry in May this year. Quite often and

quite naturally, the focus on civilian casualties is cantered on the

life and property damage caused in military operations while

insufficient consideration is given to the thousands of lives lost in

suicide attacks on civilian targets by non State actors.

Two Categories

We have to devise means to also hold non State actors accountable and

to recognize the asymmetrical nature of conflicts where democratic

states are confronted by ruthless terrorist groups who pay scant

attention to the rules of war and challenge conventional armies on how

best to protect vulnerable civilian population”.

In an age of easy international travel and advanced communications,

terrorist networks have also assumed cross-border dimensions. In many

instances, attacks are planned by individuals located in different

countries who use modern technology to collaborate for the transfer of

funds and procurement of advanced weapons. This clearly means that

terrorism is an international problem and requires effective

multilateral engagement between various nations.

For the international legal community, this poses a doctrinal as well

as practical challenge. It is because, from the prism of international

legal norms, prescriptions against violent attacks have traditionally

evolved under two categories - firstly, those related to armed conflict

between nations, and secondly, those pertaining to internal disturbances

within a nation.

While the conduct and consequences of armed conflicts between nations

- such as wars and border skirmishes - are regulated by international

criminal law and humanitarian law, the occurrence of internal

disturbances within a nation are largely considered to be the

subject-matter of that particular nation’s domestic criminal justice

system and constitutional principles.

It is often perceived that these doctrinal demarcations actually

hamper international cooperation for cracking down on terrorist cells

with cross-border networks. In the absence of bilateral treaties for

extradition or assistance in investigation, there is no clear legal

basis for international cooperation in investigating terrorist attacks -

which are usually classified as internal disturbances in the nation

where they took place.

Since there are no clear and consistent norms to guide collaboration

between nations in acting against terrorists, countries like the United

States have invented their own doctrines such as ‘pre-emptive action’ to

justify counter-terrorism operations in foreign nations.

Constraints

However, the pursuit of checking the alleged human rights violation

during a terrorist war period alone cannot be a justification for

arbitrarily breaching another nation’s sovereignty. In this scenario,

one strategy that has been suggested is that of treating terrorist

attacks as offences recognised under International Criminal Law, such as

‘crimes against humanity,’ which can then be tried before an

international tribunal such as the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The prosecutions before this Court need to be initiated by the United

Nations Security Council (UNSC).

Yet another practical constraint has been the question of holding

sovereign governments responsible for the actions of non-state actors.

While one can say that there is a moral duty on all governments to

prevent and restrain the activities of militant groups on their soil,

this is easier said than done. For example, terrorist groups are able to

organise financial support and procure weapons even in western nations

where the policing and criminal justice systems are perceived to be

relatively stronger than in the subcontinent.

Furthermore, the trauma resulting from the terrorist attacks may

justify curtailment of certain individual rights and liberties. Outside

the criminal justice system, the fear generated by terrorist attacks may

also be linked to increasing governmental surveillance over citizens and

stern restrictions on immigration. Such restrictions were not confined

to Sri Lanka and other terror-struck Asian countries.

In recent years, the most prominent example of this ‘slippery slope’

for the curtailment of individual rights is the treatment of the

detainees in Guantanamo Bay who were arrested by U.S. authorities in the

wake of the 9/11 attacks. It is alleged that they have detained hundreds

of suspects for long periods, often without the filing of charges or

access to independent judicial remedies. Stories of violent

interrogations and torture also came into light.

Even in the United Kingdom, the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security

Act, 2001, allowed the indefinite detention of foreign terror suspects.

However, due to a subsequent House of Lords decision the Government

enacted the Prevention of Terrorism Act; the British Parliament accepted

a 42-day period as the maximum permissible for detention without

charges.

The simple truth is that we cannot however impose international

conventions on terrorists who are largely unseen and unknown until they

strike and claim responsibility. It is also true that we cannot also

suspend human rights and the rule of law in our countries in the spirit

of combating terrorism. The rest of the civilians must continue to live

in reasonable peace despite the ravages of terrorism and other threats

to liberty.

But we must recognize that manmade and natural calamities occur which

at times threaten the very existence of the state and the enjoyment of

the same civil liberties. Threats to society such as terrorist war,

earthquakes and floods demand that governments should have the ability

to lawfully undertake extraordinary measures to protect citizens and the

very liberties that we so deeply cherish. |