The English episode in Ceylon

An incomplete thought:

****

“Political disturbances

may arise out of small matters, but are not therefore about small

matters.”

- Aristotle

****

Sachitra MAHENDRA

|

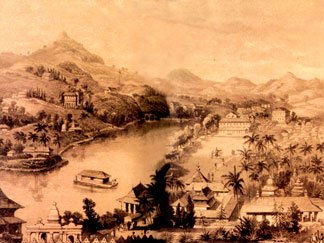

A sketchwork of ancient Ceylon taken from

‘The Last Kingdom of Sinhalay’.

|

Sri Lanka cannot speak high of a still and

smooth sovereignty before the European intrusion in 1505; the isle had

been fragile for many takeovers by its giant-built immediate neighbour,

India. However the European involvement was a turning point ushering in

a new terrain of culture. The most remarkable chapter in European

invasion is, out of the question, the English period told with a surge

of aesthetic complexity in politics and culture.

The English enjoy a well-reputed notoriety far more than their

predecessors, Portuguese and Dutch. The English was never happy with

their commercial empire set in the coastal area as predecessors, and

soldiered on inwards. But it was no cakewalk with geography, climate and

warfare beyond the ken. The English landed in 1798 but could not take up

the whole kingdom till 1815.

King Sri Wikrama Rajasinha’s rule was constantly scoffed at by his

own chieftains. The king descended from a Tamil ancestry and had issues

with his personality before the massive popularity the chiefs had. The

king cashed in on his power to trample down the rise of chieftains. A

complete English rule, however, was the last idea of the chieftains.

They had the wishful thinking of enthroning a Sinhala king with the

protectorate-model British contribution. The chieftains’ move - for some

it is a betrayal - thus drew a halt to the Sinhala royal lineage with

its last bastion Rajasinghe taken as a prisoner.

Colony management

The English had the premeditated benefit of colony management

practice which was obviously undersupplied in Sinhala rulers; this

outweighed the brilliant military techniques and offensives the

Sinhalese were equipped with. Forget about natural disadvantages, but

the British could make the best use of chieftains’ negative judgment in

outmaneuvering the Sinhalese military strategies. The 1815 achievement,

so to say, was naturally in spades for the English. Captain Elmo

Jayawardena offers a classic portrayal in his ‘The Last Kingdom of

Sinhalay’:

“This was the land, thought the Englishman, of temples and prayer, of

a religion that spoke of tolerance and harmony. People have lived here

so long, thousands of years. Simple tenants in the land of their

forefathers; civilized in culture and rich with tradition. That was

before the New World opened and the white men came. All this will soon

be finished.

Men will rise with the cry of freedom and they will be ruthlessly

crushed. When the guns become silent and the smoke clears, the land

would have been destroyed beyond recognition. That was inevitable. It

was the law of the empire, the way of the colonizer, to take what he

wanted, regardless of cost and totally oblivious to the devastating

consequences.”

With Ceylon being just one colony in the ‘infinite empire’, Britain

lived up the supremacy of global power. They held the control of

one-quarter of the world’s population by 1922; no wonder ‘the sun never

set on the British Empire’. This was the best territory for the British

to spread the influence of their political and cultural legacy.

The English, all the same, had many issues to handle with the Ceylon

rule. Many English Kalinga Maghas naturally did not wish the

preservation of Sinhala culture. However their attempts to crush down

the Sinhala culture was never to become a reality. Contrarily they had

to shake hands on preserving the Sinhala culture in Kandyan convention,

which had the backing of Kandyan chieftains as well.

The Sinhalese frustration

While some rulers were harsh destroying the Sinhalese culture, some

had other tactics. They built many Christian schools and made various

high-up positions available for local Christian converts. However the

British rule was not up to the satisfaction of the locals. A passage in

‘The Revolt in the Temple’ sketches out the frustration: “The Chiefs

were disappointed and discontented. The Sangha was even more

dissatisfied. The ascendancy of a Christian government in the Kandyan

provinces constituted a distinct menace to Buddhism. The projected

establishment of an English Seminary at Kandy for the Western education

of the children of the Chiefs further inculcated the fear of

proselytism.

The politic patronage of a Christian government was hardly a

satisfactory substitute for that of a Buddhist King, nor could the

former take the intimate part in Buddhist rites, ceremonies and

processions which the latter had naturally performed. It was with

difficulty that the Sangha was induced to bring back to Kandy that most

sacred symbol of Buddhism, the Tooth Relic. The Sangha was never fully

reconciled to the new regime….” 1817 rebellion is the upshot of

Sinhalese disappointment over the British governance. The British ruling

was forewarned on a rebellion against them towards the close of 1816.

One Duraisamy was gathering the support of masses for a rebellion that

showed signs of success.

Duraisamy’s claims to the throne had a royal weight as was exposed in

a trial later on. The British carried out the massacre of the 19th

century by wiping out the all able bodied Sinhalese men from the Kandy.

The English employed another shrewd technique of causing ethnic

uproar. A Malay appointed as a Muhandiram, a high Sinhalese rank, raked

in seeds of ethnic violence earning wrath on the British rule. The

Muslim Hadji governed the Badulla area with his army who razed villages

in numbers at their own will.

Sinhalese in the meantime had to worry about the Sacred Tooth Relic

too; whether invaders lay hands on the sacred object or not. In nature

the English had no reason to grab some locally-considered-sacred object,

though ironically they seem to have trusted royal claim possibility with

the possession of the Sacred Tooth Relic. As the rebellion marched on,

Ven. Wariyapola Sri Sumangala shifted the Sacred Tooth Relic from its

original place to Hanguranketha, a hard ground. Many rebellions were to

follow up in areas such as Matale, Dumbara, Denuwara, Walapane and

Hewaheta.

As mentioned elsewhere, the Sinhalese had the advantage of familiar

climate and geography over the rivals. Sinhalese found it easy to gun

down many soldiers in the British Forces. The British had to summon

troops from India to curb the rebellion. The English gazette

notification had offered a reward of 2000 Rix dollars to the head of

each rebel: Wilbawe, Kiulegedara Mohottala, Butawe Rate Rala and other

rebel leaders. The British, at last, could arrest most of the rebel

chiefs. Properties of 18 rebel leaders were taken away. Pilimatalawe was

exiled to Mauritius Islands.

Keppetipola and Madugalle were captured and beheaded before the

Dalada Maligawa. The British introduced this move to humiliate the

‘traitors’, but it turned out a moment of pride for the patriot to give

up life dedicated for a worthy cause in a well-revered place.

Ironical it may seem when we spot white scholars of oriental studies

in history. John d’Oyly, Lord Hamilton and a few others took to Sinhala

and Pali studies under Buddhist monks with due reverence. They in fact

persuaded the English government to have a soft attitude on Ceylon in

their capacity. Even today we see Southern hemisphere full of foreigners

despite whatever the fear bombs strewn all over cause.

Although the English went home officially in 1948, their style and

rhythm still haven’t gone out of fashion. The country remained a

dominion: from 1948 to 1972 Ceylon had a British monarch as its head of

state. Even the Bandaranaike revolution in 1956 could hardly rework the

social strata. English is considered far more superior in Sri Lanka.

Many English-speaking locals still sidestep the Sinhala-only crowd.

Aristotle plainly set the record straight with his statement; the

English episode was fuelled by a conflict that seemed small but it

spread far and wide with its own style, which is not a small matter. |