Polygamy and polyandry in Ceylon

S.Pathiravitana

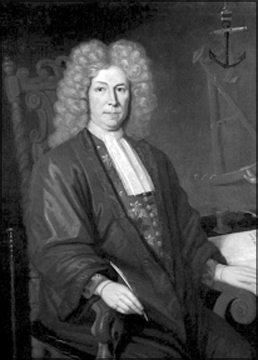

Just as Robert Knox read his Bible unfailingly during the time he was

a captive here, I never fail to dip into the book he wrote about Zeilone

whenever I have the time. He is, as we know, a cute observer using a

cuter language - English, based, according to Robert Boyle (Knox’s

Words), on the style of the Bible, the source that taught him, says

Boyle, how to write the English language. His cute observations were

generally right, but sometimes, of course, he went wrong and this

article is about a few such places.

|

|

Robert Knox

|

But first let me quote the opinions of two Englishmen with

contrasting views about the people whom they came to associate with as

their rulers. This is from Paul E Pieris, our late, great historian whom

no university in his country of birth has, as far as I am aware,

honoured him even posthumously.

In his book Sinhale and the Patriots he quotes the following

paragraphs. “The principal features of the Kandyans were merely human

imitations of their own indigenous leopard-treachery and ferocity, as

circumstances might give them an opportunity of profiting by the one or

gratifying their vengeance by the other.”

And this is the other. To the question, “Are they a docile or warlike

people?” this was the answer. “They are not warlike by any means.

They are an extremely timid race of people, very easily kept in order

by a very small party of military; particularly by the Malays.” A little

later he said, “I have seen a great deal of the world, and I have no

hesitation in saying they are the happiest race in the world.” “These,”

Pieris says, “are from the proceedings before the Special Committee of

Parliament in June 1850.”

The witness giving evidence in the first quote “with no personal

experience of Sinhale,” says Pieris and the second “Samuel Braybrooke,

who took part in the expedition and afterwards served in the Uva.” But

let’s turn to the more entertaining comments of Knox both right and

wrong.

He may have noticed that our women are more friendly, friendlier

perhaps than the women of neighbouring India, but being the Puritan that

he was he came to the conclusion that they were living in ‘whoredom.’ He

got close enough to them to ask even personal questions, like this, for

instance:

“To satisfy my owne curiosity I have often enquired of many women,

whether when they are with Child, they have the like infirmity or

desease as women here in England say they have, as to longe with such an

unsatiable desire after such things they have a mind to eate, that, if

they have it not, it will certainly produce some ill effect either one

themselves or the child they get with.”

And what do you think, the women whom he thought lived in ‘whoredom’

would have rushed to tell him that, that was so with them too? No, there

was no such haste to answer.

They neatly turned the question around and told him “...they knew

nothing of such matters and neither were they any more inclined to eate

any sort of thing when with child then not with child and lauht at me

for asking such a foolish question, saying it was more the fondness of

the husband that caused it then any necessity the woman had to longe.”.

I am inclined to think that the women were pulling Knox’s leg than

speaking the truth, for dola duka is such a common expression in the

idiom of Sinhala that we ask jokingly of even males, What is this dola

duka you have to be the President of this country? Paulusz the editor of

the second edition of Knox adds a footnote here and says that the women

seemed to have forgotten the dola duka Vihara Maha Devi had when she was

expecting Gamini.

It surely couldn’t be that the women had forgotten, for there is also

the Jataka story of the ploy a queen used her dola duka to trap a

Bodhisatva when he was born as the Vidura Panditha.

Then there is the other mix up Knox had about using the kotale - the

pot from which water is poured over some hands instead of the visitor

being allowed to handle the pot. Knox thought this was some special

honour reserved for the foreigner. But let him make the clarification:

“It is the Custom here always before and after they have eaten to wash

their mouths and Right hand with which they take up and put the rice

into their mouths, and to hold the water pot in their left hand and pore

the water out of a pipe which is Made in the pot themselves. But we

being beef eaters and lately come from eat(ing) there of, they would not

give us the pot into our owne hande boath befoe and after eating.”

This, he thought at first was a special favour being conferred on the

foreigners. That such was the custom in honouring them, was something

that he carried in his mind for a long time. But the longer he stayed in

Zeilone the wiser he grew. Had he left the country in a shorter period

he would have narrated in his book how the Chingulays conferred the

singular honour on the English people because they were English.

As he stayed on he realised what had happened, “...they poured the

water one our hands boath before and after eating, which we took as a

token of their servitude and respect they shewed, that some of the

saylours would say they never were so much Gentlemen in their lives to

have men to poure waters one their hands.”

When Knox discovered the truth he found it was not out of respect but

out of ‘disdain’ they were doing this, but once they had stopped eating

beef they ceased to be outcastes and they could now make use of the

kothale themselves.

Another instance where Knox gave the wrong message like he did about

the ‘whoredom’ of the women is in his writings about polyandry and

polygamy in Ceylon.

A man who eagerly read him was the Marquis de Sade who buttressed his

arguments for a ‘sexual Shangrila’ with instances of fathers sleeping

with daughters, or ‘treating their friends with their wives and

daughters’ and women having several husbands by referring to An

Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon. It is a difficult task to talk

to a world still dominated by Victorian morality and puritanism that

that was not a kind of ‘sexual liberation’ that prevailed in Ceylon.

As Paulusz points out in a footnote by quoting a comment by Ribeiro

who says, “...the woman who is married to a husband with a large number

of brothers is considered very fortunate, for all toil and cultivate for

her...and the children call all of the brothers their fathers.”And

Paulusz himself points out, “...under the land tenure system, the

husband could be called for active military service and fail to return

soon enough to tend his fields and crops.”

Among the other less controversial and more interesting observations

that Knox makes are on our foods and styles of cooking. He talks about

kavun which he spells as caown and tells us how it is made. But actually

what he is describing is the preparation of athiraha.

He doesn’t say whether it is tasty or not but relates how the Dutch

reacted to it and leaves it to the European reader to come to any

conclusion. “When the Dutch first came to Columba,” he begins, “the King

orders these caowns to be made and sent to them as a royal Treat. And

they say, the Dutch did so admire them and ask if they grew not on

Trees, supposing it past the Art of man to make such dainties.”

Knowing the Dutch and their very diplomatic ways only too well, one

doesn’t know how to react to this very flattering comment. But I must

say this for athiraha and mung kavun they are the tastier Sinhala

sweetmeats I enjoy if they are made with good kitul paeni and kitul

jaggery.

Robert Knox’s An Historical Relation of Ceilon is not a book that can

be taken in one gulp as it were. It has to be taken sip by sip and that

means a lifetime of reading, but reading always between its lines.

As an after thought here’s some more thinking about polyandry. While

reading Ian Goonetileke’s interesting collection of impressions made on

Americans visiting this country, I came across what Townsend Harris

observed when he was on his way to take up the position of being the

first Consul General to Japan.

When he touched down at Galle, he found he had to take a coach ride

to get to Colombo. When the coach stopped for breakfast at a rest house

on the way he describes what happened. The rest house was run, he says,

“...by three Cingalese brothers, who have one wife. On stopping there

the second time, I asked the woman which she would like the best; to be

one of many wives to one man, the sole wife of one man, or her present

situation.

She spat at the idea of polygamy, shook her head at a single union,

and was emphatic in praise of polyandry. After some pressing she said

the youngest of her husbands was her favourite, but that all were kind

to her.” |