The United Nations and perspectives on good governance

Dr. Ruwantissa ABEYRATNE

|

The United Nations: Empowered by the member States

|

Current political and diplomatic problems mostly emerge as a result

of the inability of the world to veer from its self serving

concentration on individual perspectives to collective societal focus.

This distorted approach gives rise to undue emphasis being placed on

rights rather than duties; on short-term benefits rather than long-term

progress and advantage and on purely mercantile perspectives and values

rather than higher human values.

At the heart of international politics in the United Nations. Often

one hears statements like “the United Nations failed”(for instance to

stop the genocide in Rwanda or ethnic cleansing in the Balkans) or “the

United Nations succeeded” (to stop the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait).

This misconception obfuscates the complex reality that the United

Nations is basically an intergovernmental organization in which the key

decisions are made by governments representing States.

In other words, the United Nations is empowered by the member States

to carry on its tasks and not the other way around.

Although the Charter of the United Nations initially provides

language starting with “we the peoples of the world” in effect the key

players who call the shots in the United Nations system are the

governments themselves. For instance, when it is said that the Security

Council took a decision, what is meant is that representatives of

fifteen States made that decision.

Councils

This is true also of the various specialized agencies such as the

World Meteorological Organization and the International Civil Aviation

Organization, both of which have Councils that take the decisions and

are representative of member States.

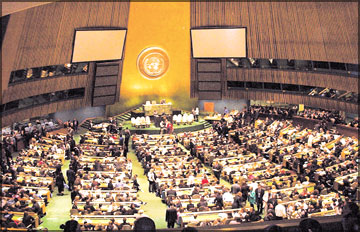

Over its sixty years of service to the international community, the

United Nations has, through its General Assembly and Security Council

adopted numerous resolutions.

This article will examine the extent to which the Member States of

The United Nations are bound by such pronouncements through a legal

analysis of how far the United Nations Organization is empowered by

States to adopt such resolutions and directives.

The first step toward such an examination would be inquire into the

nature of the United Nations. It is represented and directed by its

member States.

Therefore, it is incontrovertible that universal participation in the

United Nations is indispensable if The UN were to effectively implement

the provisions of the Charter of the United Nations. Sixty years of

symbiotic existence have shown that States need the UN needs their

membership.

An organization such as the UN is tasked primarily to provide a

certain predictability about its members by promulgating norms for the

conduct of its Contracting States. Of course not all those norms are

binding and not all of them are adopted with the same degree of

formality.

However, certainly all of them provide guidance to States. This

situation has to mesh with the basic inquiry as to whether the UN, as an

international organization, has been given direct authority over

individuals or States.

Powers

The question arises as to whether a contracting State is formally

bound by a Resolution of the United Nations, particularly when such a

State has no convincing argument that it is impracticable to implement

such a resolution. International organizations can generally only work

on the basis of legal powers that are attributed to them. Presumably,

these powers emanate from the sovereign States that form the membership

of such organizations.

Therefore, the logical conclusion is that if international

organizations were to act beyond the powers accorded to them, they would

be presumed to act ultra vires A seminal judicial decision relating to

the powers of international organizations was handed down by the

Permanent Court of International Justice in 1922 in a case relating to

the issue as to whether the International Labour Organization (set up to

regulate international labour relations) was competent to regulate

labour relations in the agricultural sector.

The court proceeded on the basis that the competence of an

international organization with regard to a particular function lay in

the treaty provisions applicable to the functions of that organization

and that the determination of such competence would be based on

interpretation.

In this instance the Court was of the view that, in its

interpretation of the ILO treaty, the organization had the power to

extend its scope of functions to the agricultural sector.

However, this principle of implied extension should be carefully

applied, along the fundamental principle enunciated by Judge Green

Hackworth in the 1949 Reparation for Injuries Case - that powers not

expressed cannot freely be implied and that implied powers flow from a

grant of express powers, and are limited to those that are necessary to

the exercise of powers expressly granted.

The universal solidarity of the United Nations member States that was

recognized from the outset at the establishment of the Organization

brings to bear the need for States to be united in recognizing the

effect of UN policy and decisions.

This principle was given legal legitimacy in the ERTA decision handed

down by the Court of Justice of the European Community in 1971.

The court held that the competence of the European Community to

conclude an agreement on road transport could not be impugned since the

member States had recognized Community solidarity and that the Treaty of

Rome which governed the Community admitted of a common policy on road

transport which the Community regulated.

It should be noted that the United Nations does not only derive

implied authority from its Contracting States based on universality but

it also has attribution from States to exercise certain powers.

The doctrine of attribution of powers comes directly from the will of

the founders, and in the United Nation’s case, powers were attributed to

the United Nations when it was established as an international

organization to administer the provisions of the UN Charter.

In addition, the United Nations could also lay claims to what are now

called “inherent powers” which give the Organization power to perform

all acts that the Organization needs to perform to attain its aims not

due to any specific source of organizational power but simply because

the United Nations inheres in organizationhood. Therefore, as long as

acts are not prohibited in The UN Charter, they must be considered

legally valid.

Duties

Over the past two decades the inherent powers doctrine has been

attributed to the United Nations Organization and its specialized

agencies on the basis that such organizations could be stultified if

they were to be bogged down in a quagmire of interpretation and judicial

determination in the exercise of their duties.

The advantages of the inherent powers doctrine is twofold. Firstly,

inherent powers are functional and help the organization concerned to

reach its aims without being tied by legal niceties.

Secondly, it relieves the organization of legal controls that might

otherwise effectively preclude that organization from achieving its aims

and objectives. The ability to exercise its inherent powers has enabled

the United Nations to address issues that are not directly within its

mandate but directly or indirectly impact its core functions.

Classic approach

With regard to the conferral of powers by States to the United

Nations, States have followed the classic approach of doing so through

an international treaty. However, neither is there explicit mention of

such a conferral on the United Nations in the Charter of the UN, nor is

there any description of the United Nations’ powers.

Of course the Security Council can impose sanctions on States that

are deemed to act inconsistently with the principles oft the Charter

Therefore States have not followed the usual style of conferral of

powers in the case of the United Nations, which, along the lines of the

decision of the International Court of Justice in the 1996 WHO Advisory

Opinion case was that the powers conferred on international

organizations are normally the subject of express statement in their

constituent instruments.

This notwithstanding, it cannot be disputed that the United Nations

member States have conferred certain powers on the UN to perform its

functions independently. For example, the United Nations is a legal

entity having the power to enter into legal agreements with legal

entities including other international organizations with regard to the

performance of its functions.

Conversely, an international organization must accept conferred

powers on the basis of Article 34 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of

Treaties which stipulates that a treaty does not create rights or

obligations of a third State without its consent.

This principle can be applied mutatis mutandis to an international

organization such as the UN. The conferral of powers on an international

organization does not ipso facto curtail the powers of a State to act

outside the purview of that organization unless a State has willingly

limited its powers in that respect.

This principle was recognized in the Lotus Case where the Provisional

Court of International Justice held that a State can exercise powers on

a unilateral basis even while the conferral to the Organization remains

in force. The Court held that restrictions upon the independence of

States cannot be presumed.

The United Nations’ conferred powers enable the Organization to adopt

binding regulations by majority decision. However, States could opt out

of these policies or make reservations thereto, usually before such

policy enters into force.

This is because States have delegated power to the UN to make

decisions on the basis that they accept such decisions on the

international plane. In such cases States could contract out and enter

into binding agreements outside the purview of the United Nations even

on subjects on which the UN has adopted policy.

Given the United Nations’ profile as a self standing legal entity,

the Organization would be responsible for its internationally wrongful

acts.

As to the issue whether a State which has delegated powers to the

United Nations would be responsible for the wrongful acts of the

Organization, a State is not bound by the Organization’s exercise of

delegated powers and therefore it cannot be necessarily assumed that

such acts would be attributable to the States unless such acts were the

effect of the State’s own acts or omissions.

Article 1 of the Articles of Responsibility of the International Law

Commission (ILC) expressly stipulates that every internationally

wrongful act entails the international responsibility of a State.

The State cannot escape responsibility by seeking refuge behind the

non-binding decision of an Organization in the case of delegation of

powers. This is also the case where a State aids and abets an

Organization to perform an internationally wrongful act.

Activities

The General Assembly and the Security Council are composed of

Contracting States. The General Assembly has delegated activities

concerning matters of international security to the Security Council as

well as delegating other areas of work to other Councils of the UN such

as the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and the Trusteeship Council.

Therefore it would not be incorrect to assume that any resolution

adopted or decision taken by the UN Security Council can be imputed to

the member States of the UN which have delegated powers on these

Councils.

Not bound

However, States retain the powers to act unilaterally and they are

not bound to comply with obligations flowing from the Organization’s

exercise of conferred powers. States which have delegated powers on the

United Nations have the legal right under public international law to

take measures against a particular exercise by the UN of conferred

powers which is considered to be detournement de pouvoir, ultra vires or

an internationally wrongful act with which the objecting States do not

wish to be associated.

A State could also distance itself from the State practice of other

Contracting States within the UN if such activity is calculated to form

customary international law that could in turn bind the objecting State

if it does not persist in its objections.

As discussed earlier in this article, a significant issue in the

determination of The United Nations effectiveness as an international

organization is the overriding principle of universality and global

participation of all its member States in the implementation of UN

policy.

This principle, which has its genesis in the Charter of the United

Nations, has flowed on gaining express recognition by legal scholars.

This is what makes the United Nations unique and establishes without any

doubt that the UN is not just a tool of cooperation among States.

In the years to come, citizens of the world will scrutinize both

their governments and those of foreign nations whose responsibility it

is to ensure good governance and the continuity of the world

communications systems. The politician, diplomat and lawyer will

increasingly turn toward principles of international law to determine

the best course of action in crisis. |