Pathiraja falls flat on the propaganda road to Jaffna

H. L. D. Mahindapala

|

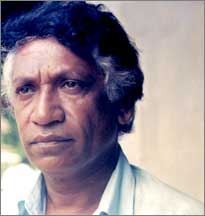

Dharmasena Pathiraja

|

Film Review: It is with great expectations that I went to see

Dharmasena Pathiraja's latest film, In search of a road, screened at the

Union Theatre, Monash University, Melbourne. Since there was hardly any

literature available about the film I gathered from what I heard that it

was a docu-drama about A-9 Road - the main road that links the North to

the South.

I have not had the opportunity of seeing any of his films before, but

I was buoyed by the pre-screening announcement which promised a moving

film by "one of South Asia's prominent film directors". A loyalist of

Pathiraja introducing the film gave the distinct impression that the

film was produced by a director comparable to that Satyajit Ray perhaps,

Satyajit Ray XVI!

The film opened with Tissa Abeysekera's sandpapered throat labouring

to voice a message of some messianic proportions, loaded ominously with

impending gloom and doom. It was a voice meant to sound heavy and

important but it didn't ring true because his running commentary came

across like Big Brother telling the audience what to think and how to

think.

The opening shots of the Fort Railway station, with the ubiquitous

crow feeding on whatever it had picked, signalled that it was not about

the A-9 road but about the railway line that linked the North to the

South in 1905 under the British colonial masters.

Pathiraja focuses on this road-rail link as the symbol of unity that

brought the North-South regions and cultures together in the good old

days of the British Raj when the son shone in Colombo while the father

gathered hay in Jaffna. As the credits rolled up the audience was told

that it was a concept developed by Pathiraja.

The concept in itself is good. It had a lot of potential. But as the

film unreeled it became clear that Pathiraja hadn't a clue as to how he

could develop or dramatise his theme to make it a cinematic experience.

From his point of view the journey he begins is undoubtedly of some

importance but he ends up going nowhere. The potential that was there in

the concept had evaporated by the time it was translated into a film. It

raises doubts as to whether he had the capacity to arrive at his

destination when he went in search of a road without a creative and

perceptive ability to find his way.

At best, the film is an attempt to go on a sentimental journey into a

lost past with episodic, disconnected stops at various railway stations,

between the North and South - a rather dreary presentation which had all

the hallmarks of a hired tour guide parroting place names without

informing anything other than the familiar rumours and usual propaganda.

I must confess that it did evoke some interest in my friend seated

next to me because he happened to be a former executive of Ceylon

Government Railways, as it was known in colonial times, who had some

nostalgic memories of these stations.

Other than that there was nothing dramatic to hold the theme together

as the various episodes, picked from various places and times, surfaced

erratically on the screen. The denouement was jumpy and sporadic with

the commentator trying to stitch the events together with his belly-deep

voice.

Pathiraja also shuttles between the present and the past. It is in

trying to weave the present into the past that he fails mostly. The

present is exploding with ethnic politics which has left Jaffna in a

heap of rubble and ruins. His camera lingers painstakingly over Jaffna.

He attempts bluntly to inject his version of politics into the Jaffna

landscape.

His passage to Jaffna is a journey into ethnic politics. Here he

exposes himself as a propagandist who had sacrificed his integrity as an

objective film maker. He has allowed his political biases to take over

the film which in turn has turned the film into a run-of-the-mill

political tract.

His tendency to lean heavily towards propaganda has stripped the film

of the essential quality and artistry expected of any credible film

maker. Not having seen any of his earlier films I am in no position to

comment on his previous films. But his railway journey indicates

unmistakeably that, at the age of 60, he has run out of steam, to use a

metaphor from his railways.

Even from his propagandistic point of view it lacked coherence to

give meaning to the North-South relations geographically. It would have

been quite appropriate and meaningful to the viewer - especially the

foreigners who are clueless about the geography of Sri Lanka to have

seen an animated shot of a train, or even a plain line, snaking and

plotting the railway track going up North on a map of Sri Lanka, making

the usual stops at Omanthai, Pallai, etc.

This would have given the viewers (including Sri Lankans who had

forgotten their topography) an overview of the route and railway

stations that linked the North to the South.

Pathiraja presents a drab shot of a news item of 1905 picked from the

archives which announced the opening of the railway line to Jaffna. The

visual impact of a train chugging up North on a map of Sri Lanka could

have been developed to convey the theme of the railways linking the

North and the South, the past and present, cutting across political and

racial divisions.

It would have visually described the symbolism more convincingly than

a shot of an unreadable newspaper clipping which in filmic terms was

redundant because the commentator was harping on it ad nauseam. In the

film Pathiraja stops at various stations up North but for the

uninitiated it could have been anywhere from nowhere.

Films are made to dramatise issues, themes, plots mainly with visual

aids. The audio tools are merely an adjunct to heighten the visual

impact. But in Pathiraja's film the audio takes over the role of visuals

obviously because he has lost the imagination to use the eyes of the

camera to develop his theme. Instead, he has passed the buck to the

voice of the commentator.

Besides this basic technical failure to present a visual overview, or

to use visuals to enhance his theme, the episodes he had put together in

a haphazard way to push the usual, threadbare Tamil propaganda did not

elevate him to the advertised level of "a leading South Asian director".

They were all contrived scenes skewered like roughly cut pieces of

tasteless meat on a satay stick. What is more, the film ran on fake

characters, unconvincing day-dreamers wandering among the deserted ruins

of Jaffna, and two-bit actors, stiff as bamboo, pretending to be Muslims

or Tamils.

While these characters were alighting from three-wheelers, cars,

buses or trains - a prominent feature in the film - the sawing voice of

Tissa Abeysekera was running in the background trying to connect all of

them into some apocalyptic drama which was not there on the screen.

The text of his commentary was overloaded with maudlin sentimentality

aimed at squeezing last drop from tear ducts. Pathiraja clearly has

borrowed his friend's voice to replace what he could not produce in

cinematic images.

Docu-drama is supposed to dramatize raw reality but Pathiraja is as

successful in this as a two-legged horse attempting to jump over a

six-foot wall. His ambitious attempt to translate his concept into a

credible reality should never have left his cranium.

The most authentic documentation and drama came from the archives of

the Tamil Tigers. The shots of the Tigers going on the offensive firing

on all cylinders, the flying explosives uprooting palmyrah trees were of

documentary quality that dramatised the Tigers as efficient and trained

cadres engaged in their usual killing spree.

Patently, Pathiraja has had access to the archives of the Tigers.

This may also explain the film's tilt towards the political line of the

Vanni. It was supposed to promote peace and unity but it was going in

the opposite direction of justifying the mono-ethnic politics of the

North that paved the path to violence. It is the lack of balance in the

footage that condemns the film as a poor propagandistic exercise.

For instance, in one episode a Jaffna Tamil public servant, boarded

in the front room of a Sinhala home, comes out, all packed and ready, to

leave the South and head North because, as he tells his Sinhala

landlady, he can't work in Sinhala. This is political propaganda of the

usual kind intended to demonise the Sinhalese.

In other words, Pathiraja confirms that the vast majority of the

Sinhala people must learn the language of the Tamil bureaucrat, as in

colonial times, without inconveniencing the bureaucrat to learn the

language of the people if he is to function effectively in serving the

public.

Like all other political pundits who had distorted the Sinhala Only

debate Pathiraja is highlighting this issue of a Tamil bureaucrat's

refusal to work in the language of the people to portray the Sinhalese

as the villains in his film.

The claim of a Tamil bureaucrat to work under the colonial rules is

recognised as an inviolable right whereas the inalienable right of a

citizen to be served in his/her mother tongue the only language he/she

knows is denied as racism, or majoritarianism.

An elected democracy in the post-independence era had a right to

serve its citizens in the languages of the majority (Sinhalese) and the

minority (Tamil). In the twisted political imagination of the

left-wingers and Western-oriented brown sahibs the natives particularly

the Sinhala majority (75%) had no right to upset the privileged colonial

way of life by demanding that they be given a place, particularly in

running an administration in their mother tongue.

In fact, S. J. V. Chelvanayakam, the father of Tamil separatism, went

from kachcheri to kachcheri urging the Tamil public servants not to

learn Sinhala. The logic of his linguistic politics was that the Sinhala

people must accept the claim of the Tamil public servant to administer

the nation either in English or Tamil.

This is typical of the Northern Tamils manoeuvring to impose their

minority rule on the majority. This is also contradictory to the

universal rule of public servants in any country acquiring competency in

the language/s of the public to deliver administrative services

effectively.

Except in countries run by colonial masters and dictators, all

nations function in the language of the majority with reasonable

concessions to the minorities. Australia, for instance, has roughly 152

communities (leaving aside the original Aboriginal inhabitants) and

there is only one language: English.

According to the current trend in Australia any Tamil who intends

migrating to Australia must pass a test in English. As far as I know, no

Tamil has protested, or taken his bags and gone back to Vanni on this

score. On the contrary, more Tamils (some of whom may not pass the test)

want to come over despite the language disability.

Furthermore, Tamils have migrated to all corners of the earth and

worked successfully, as they have done in Sri Lanka, without knowing a

word of French, Norwegian or even English. In Western countries Tamils

consider it a privilege to learn and function in non-Tamil languages. In

Sri Lanka, even after their language has been given its due place, they

take up arms.

In playing up the claim of his Tamil public servant leaving the

South, Pathiraja endorses his claim that the Sinhala public (75% of the

population) must learn the language of the Tamil public servant to give

him equality with the Sinhalese, not to mention his life-long pension,

free railway tickets for him and his family, and all the perks

(including thumping dowries) of the colonial clerkdom ruled by Jaffna

Tamils.

Pathiraja's blinkered view has brushed aside the plight of the

oppressed Sinhalese who were denied their right to use their language

under five centuries of colonialism.

He was conveying implicitly that the old colonial privileges given to

one section of the community in the North should have been continued

even though it dispossessed and disempowered the majority of Sri Lankans

who deserved their historical rights to be restored at the end of the

ordeals of colonialism.

Pathiraja goes along blithely and blindly with the Orwellian concept

that guaranteed Only to the Tamils a right to be more equal than others.

If Pathiraja was committed to maintain some semblance of balance in

his politics he should have introduced a few counter-points asking, for

instance:

1. If it is good for iconic countries of democracies like France and

UK to run their nation exclusively in the language of the majority,

denying emphatically the linguistic claims of the minorities, what is

wrong with the Sinhala Only Act that was followed by granting Tamils the

reasonable use of Tamil - a recognition of a minority right non-existent

in France, Australia, UK or USA?

2. Even after the much-maligned Sinhala Only Act that forced

Pathiraja's Tamil public servant to go to Jaffna how did other Tamils in

the public service like Sharvananda achieve the status of the Chief

Justice, or Siva Pasupathy reach the top of the legal department to

become the Attorney General, or Admiral Rajan Kadiragamar get promoted

to head the Navy, or Rudra Rajasingham become the IGP and, above all,

Lakshmi Naganathan, daughter of a leading light of the Federal party,

Dr. E. M.V. Naganathan enter the Foreign Service without going through

the competitive process of selection through a public examination that

was compulsory for Sinhalese and Muslims?

3. Why didn't he focus on the English-educated Sinhalese who left the

public service taking the full pension with them like the Tamils to

enjoy their life in retirement or to be employed gainfully in other

lucrative jobs?

4. In presenting Tamil public servants as victims of Sinhala Only

Act, Pathiraja wittingly embraced the Tamil propaganda line which

ignored the fact that Sinhala and Burgher public servants too had to

learn Tamil if they were to fulfil their role as public servants serving

all communities.

So why present only the Tamil man as the victim of an act that was

meant to democratize a colonial administration giving rightful access to

the majority of the people who never knew English?

5. Every single Tamil doctor, lawyer, academic, accountant, engineer

and other professional who thrive in the Tamil diaspora came out of the

free education system that gave equal opportunities to Sri Lankans in

the post Sinhala Only act era.

Has he asked any one of them what discrimination they faced which the

Sinhalese had not faced? If it is language, did not the Sinhala youth

take up arms before the Tamil youth also on the language issue - the

English language that rules the nation to this day despite the Sinhala

Only act of 1956?

Pathriaja would have maintained a respectable balance if he gave due

weight to the multiple socio-political dimensions of his Jaffna man

carrying his bag and baggage to "Yal Devi". (Incidentally, there's not a

word about "Yal Devi" - one of Sri Lanka's famous train services).

The film confirms that Pathiraja has waded into politics with the

usual baggage of misplaced sympathies of the loony left without

examining the pros and cons of the distorted language issue exploited by

the mono-ethnic extremists of the North who were bent on severing the

connections with the south.

Incidentally, his politics is relevant for this review because it

runs as a central theme in his film. It is in presenting a one-sided

view of the politics that his film has degenerated into a crude exercise

in propaganda.

Besides, the dark, chubby man who introduced the film began by

politicizing it when he said that there should be no majorities or

minorities but there should be only equal people.

Translated, it means that the Sinhala majority has not given equality

to the minority Tamils. Obviously, he has not heard of the revised

thinking of Prof. S. J. Tambiah, Radhika Coomaraswamy and V.

Anandasangaree. Radhika Coomaraswamy told the BBC that according to

recent research there has been no economic discrimination against the

Tamils. Where does this leave Pathiraja's pro-Tamil propaganda?

The politics of this film is also stuck in the outdated Marxist

concepts which Pathiraja absorbed when he was a green horn at Peradeniya

University.

Their political fixations are incurable. That is acceptable because

some mental diseases are incurable.

But for Pathiraja to expect applause as a creative film director he

has to go beyond his narrow politics into universally acceptable values

and criteria. If he was producing a docu-drama, as he claims, then it

was his moral duty to conform at least to the realities experienced by

all communities. But in surrendering to Northern politics he has

abandoned the refinements of art to promote crude propaganda.

Neither the dramatisation nor the documentation has lifted him above

the level of a hyper-active kid with a home video, taking movies of

grandpa's birthday party in the backyard. Pathiraja has failed to

connect effectively either to his theme or to the realities of the

politics that have come in between the Northern and the Southern

communities. It is pretty clear that he has bitten more than what he can

chew.

The film ended with the trite motherhood statement that all

communities must get together. In short, Pathiraja's mountain has

laboured to produce a mouse. The polite clapping at the end of the

screening indicated the response of the audience. His propagandistic

bias was apparent even to some discerning Tamils. But I am told that

there were a couple of Tamils who shed a tear or two. Given the

pro-Tamil bias in the film that was predictable.

The converted always have ready-made stocks of tears for their cause.

His merit as a creative film director, who could cut across barriers of

prejudice, would have been confirmed if he won the accolades flowing

from Sinhala tears. It is difficult to move the hearts and minds of

non-partisan viewers with blatant political propaganda.

As a concluding footnote, it could be mentioned that the only things

that were visibly moving in the film were cars, buses, train and three

wheelers! |