|

DAILY NEWS ONLINE |

|

|

|

OTHER EDITIONS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

OTHER LINKS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The spice of lifeFrom very ancient times spices have played an important role in promoting trade between the East and the West. In many civilized nations of the ancient world, spices such as aromatic fruits, flowers, bark or other plant parts of tropical origin, were in great demand in tickling the taste buds of gourmets.

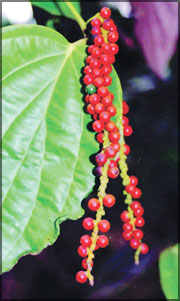

Egyptians used them in cooking, medicine, embalming, perfumes and as incense. Cinnamon and cassia (native to South East Asia and China) are mentioned in ancient Egyptian records, thus indicating the active spice trade that prevailed between ancient Egypt and the East. Ancient Greeks wanted cinnamon, cassia, black pepper and ginger from India and Sri Lanka. It was the lure of spice that brought the Arab traders in the 12th and 13th centuries; their descendants are the Muslim Moors in Sri Lanka. Portuguese, Dutch and finally British began arriving in the shores of Sri Lanka from the 16th century in search of the spice of life. Spices, such as cinnamon, black and white pepper, cloves, nutmegs, mace, ginger, turmeric, saffron, had a colourful history in Sri Lanka by opening up the trade routes to the west, and determining the dynamics of power in the Island nation.

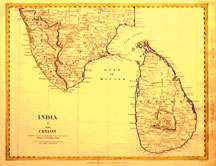

From the earliest days of navigation nomadic Arabs and ancient Phoenicians were trading with southwest India and Sri Lanka. During the early pre-Christian era, sea trade between the Middle East and Sri Lanka was in the hands of Arabs. They transported spices, incense and oils from the East by land as well as through the Persian Gulf to Arabia. Southern Arabia became the great spice emporium of the ancient world. The ports of ancient Sri Lanka played an important role both in the foreign trade of the island and in the inter-oceanic commerce between East and West. When ancient Sri Lanka's seat of power was located in the Raja Rata of the north central region, there were two major ports, named as Jambukola and Mahatittha, used in the trade of spice and other merchandise with the outside world.

The Mahavamsa mentions that those two ports were strategically vital for navigation in the earliest historical eras of the island. Jambukola now identified as Sambalthurai, in Kankesanthurai (Jaffna Peninsula) functioned as the port to North India especially to Tamralipti in Bengal, which in turn was the transit port to Sri Lanka. Pali chronicles, Sinhala literary works and inscriptions found in Sri Lanka shed light upon the antiquity of navigational importance of Sri Lanka ports. It is recorded that the seamen of Ptolemaic Egypt were terrified to risk a long voyage close to the Arab controlled shorelines of India and Sri Lanka. During the reign of Ptolemy II and Ptolemy III, seaports were built along the shores of the Red Sea. Around 116 BC, while Ptolemy VII was the king, a Greek sailor managed to sail with the winds and reach India's southwest coast, marking the beginnings of a thriving Egyptian, and later Roman, spice trade. Ptolemy XI bequeathed Alexandria to the Romans in 80 BC and by 40 AD it had become not only the greatest commercial centre in the world but also the pre-eminent emporium for spices. The rapid growth of Roman trade with southern India and Sri Lanka in the First, Second and Third centuries AD led to the introduction of a direct route from Red Sea ports to the ancient port of Muziris (Kodungalloor) in central Kerala. Roman ships left in July, at the height of the monsoon season and returned with the reverse northwest monsoons in November. They used the most southerly course even in the worst monsoons; especially as the sighting of the Lakshadweep Islands two hundred miles from the mainland gave them an excellent guide to their destination. The Roman trade began to weaken during the Third century AD. Arab and Ethiopian middlemen began to take control of the trade. After the fall of the Roman Empire, Arabs held the control of the spice trade for a long time. By this time Venice had become a great sea power and controlled the Adriatic Sea. Arab traders took their merchandise to Alexandria and the Venetians dominated in the distribution of pepper and other spices from the Middle East to Western Europe. Major Middle East market centres were Constantinople (now Istanbul) and Alexandria. With these virtual monopolies the spice prices skyrocketed and only the rich were able to afford it. The higher prices frustrated other European nations and the quest for a new source of spices fuelled the enthusiasm of the great explorers of the Renaissance. During the latter half of the Fifteenth century the Spanish and the Portuguese built stronger ships and ventured abroad in search of a new ocean route to the spice producing countries of the east. Portugal was convinced that India could be reached by sailing around the coast of Africa. The famous Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama arrived in Kerala in 1498. This voyage marked the beginning of the Portuguese dominance of the lucrative spice trade from India. The year 1506 ushered in a new era of bustling spice trade between Portugal and Sri Lanka, when the first Portuguese arrived in the island. The Portuguese foray into the spice trade with the East was a result of the conquest of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453, which marked the decline of Venice. The advent of the Portuguese through the newly discovered ocean route totally ended the Arab and Venetian monopoly of the spice trade. In the following years, Lisbon became one of the wealthiest cities in Europe. The Dutch, full of energy and zeal after gaining their freedom from Spain in the Sixteenth century, made their first voyages to the East Indies during 1595 through 1598. In 1602 the Dutch East India Company was founded. Then came the British East India Company in 1600 under the royal charter granted by the queen Elizabeth I. By 1663 the Dutch gained trade supremacy in the east by defeating the Portuguese. Conflict erupted between the Dutch and English in the following years and the English East India Company eventually broke a 200 year Dutch monopoly. Today the monopolies are long broken and black pepper is freely traded in world commodity markets. The consumption of spices grew astonishingly in the days of the Roman Empire and pepper became the most common spice in medieval Europe. Before the days of refrigeration and the invention of other methods of preservation, pepper and salt were the only preservatives available to man. It was a status symbol of fine cookery and a description of a lavish feast invariably mentioned pepper, if not other spices. The rise of French cuisine during the Seventeenth century put an end to over spicing of food and milder spices and herbs slowly replaced black pepper. The story of spice trade is not complete without reminding the reader that it was the lure of spices that saved Buddhism from totally vanishing in Sri Lanka. When the Portuguese occupied the island and had total control of her spice trade, the Portuguese had literally chased away the Arabs from the Indian Ocean monopoly of spice trade. If by chance the Arabs had continued in their spice trade in the Indian Ocean and Sri Lanka without the Portuguese coming into the scene, they would have converted entire Sri Lanka to Islam, similar to what the Arabs did in the Maldive Islands. According to archaeological and other evidence, the people of Maldive Islands were originally Buddhists and their ancients spoke and wrote a dialect very close to the Singhalese language. The Portuguese became the first mariners and traders in Europe to devise a plan for invading the Moslem-operated spice trade from Goa to Sri Lanka to the Indonesian "Spice Islands", from around 1505 AD. (This article is written by the author/publisher of two new books launched recently. They are: "Rituals, Folk Beliefs and Magical Arts of Sri Lanka, the New Version" and Alien Mysteries in Sri Lanka, the New Version". The two books are available at leading bookshops.) |

|||

|

|