|

A compendium of village centred experiences

by Professor Sunanda Mahendra

When the great French writer Marcel Proust wrote his reminiscences

titled in English as 'remembrances of things past' one would not have

imagined that it would turn to be a great voluminous novel for they were

some of his personal experiences and observations of the childhood days.

It is recorded that he had so much of experience with his past that

they all tightened with the other fictitious experiences had gone into a

great memorable work.

For a moment I was reminded of this reading experience which I had

long time ago, when I read the latest book of the well-known translator,

broadcaster and administrator Amaradasa Gunawardhana titled 'Ma lama

kalaye mage gama' [my village in my childhood] a collection of

belles-lettres, consisting of 26 short and long essays.

The essays are quite readable and full of wit and wisdom linked to

the folk patterns of narration intermixed in dialogue, prose and verse

wherever necessary.

AG recollects how he had seen the change in the two worlds, in a very

detached form, the world of his past and the world of his present

existence. What is significant is that he had not meant to write a book,

but the bits and pieces he had been writing from time to time had

automatically transformed into a book.

In most of his expressions he is seen cathartic for the experiences

embedded are spontaneous overflows of emotions bordering on nostalgia.

In the first instance AG outlines the geographical borders of his

village Mullegama and remarks how it is different from those other

villages as described by many a Sri Lankan writer like Martin

Wickramasinghe or Leonard Woolf.

Sensitive snapshots

The memorable moments in the life of his childhood and the use of

such classroom material like the slate [gal lella], the leisure time

spent in the nearby wood, the games played with his friends, and the

imitative actions of the adults and the village folk players, the birds

and animals with whom they move about, all go to make short and

sensitive snapshots of life gone by.

He also makes it a point to jot down his personal and known folk

notes on household pets like dogs and cats and birds like sparrows and

parrots with whom the human beings from time immemorial had been

accustomed to live as relatives.

In these notes the folklore play a vital role as it had moulded the

wisdom and the outlook of the common man in the agrarian sector.

I was amused when I read with interest some of the folk games and

plays long forgotten by us is once again brought to the forefront

through these pages.

Even from a linguistic point of view the terms used in these games

become a study for the modern generation. For instance the terms like 'nocirial'

[for no clearance] 'istand'[for stand] 'cirialnoroad' [for clear no

road] have been used as an influence from an English game of a similar

type.

Number of events relating to the nature of the village school is

recorded with various anecdotes connected with teachers, parents,

students, school concerts, debates, inspectors, annual educational

trips, musical recitals and theatrical activities , and the advent of

well wishers who so wish to develop the village education.

In all these the underlying factor is the innocence. Then we

encounter the spiritual side of the village via the village temple which

is the abode to which most people go in search of a meaningful mission

the gathering of merits.

The writer AG records with a poetic sensibility the nature of the

simple villager in search of his own identity to be a good human being,

listening to the bana sermon of the priest, observing sil on poya days,

and bringing the dana or the alms to the monks from a long distance to

the temple.

The village temple is denoted as the central nervous system of the

village and the monks are treated as the opinion leaders from whom the

necessary advice is sought.

Village boutique

The village boutique and the village fair too take an interesting

turn of events to the villager. The nature of the traders [mudalali] is

outlined vividly portraying the crude and the sensitive nuances of

individuals in the buying and selling of commodities where some of the

urban systems are linked with those of the village giving way to a kind

of invisible exploitation.

How the villagers face various annual events such as the dawn of the

new year festive mood, the vesak celebration with children and adults

preparing for the making of pandals, lamps and lanterns and the advent

of the pilgrimage period [vandana samaya] of the poson are recorded.

How a marriage is arranged and takes place amidst a gathering is not

so easy as one would imagine in the village that AG cites in chapter

nine of his book for the reader is given the impression that it is a

yeoman task and a responsibility from the point of views of parents,

finding the suitable partners, sending match makers, scrutinizing

horoscopes, negotiations between families, finding auspicious times, the

decisive factors of the wedding ceremony, extending the invitations to

relatives and well-wishers and villagers which in turn becomes a

collective function with background preparation unfathomable.

Though we have observed all these factors, over a long period of

time, yet when they are recorded in this manner one would feel that the

interpretations matter. Some of the most exciting episodes pertaining to

the village rituals like exorcism inclusive of devil dances and magical

rites are recorded with personal comments in chapter ten.

The average villager believes [I feel for the most part he still

believes] that most of his problems and illnesses are caused as a result

of misadventures with devils which lurk in the folklore.

AG in the mood of an investigator-cum-researcher tries to interpret

these mystical areas making us feel that he is somewhat above the plane

of his beloved villager, yet possesses a feeling of pathos towards him.

This chapter on exorcism could inspire the student of rituals and

theatrical activities. The villagers' attitude towards death, rain,

floods, droughts, climatic conditions, birth and rebirth, merit

gathering are recollected in certain sections in a narrative form.

The last few chapters [14, 15 and 16] are devoted to aspects of

gradual urbanisation, the catalyst of which is inevitably the coming of

a post office, the development of transport services, and other forms of

communication, together with entertainment factors with gambling at its

helm.

But the writer AG is more nostalgic when it comes to the areas of

agrarian culture in his village. This book from a synoptic view is a

mirror that reflects faces, gestures, manners, follies and foibles of

village folk who lived several decades ago.

[email protected]

A gentle reminder to all of us inequality

Author: Daya Dissanayake

Available at leading bookshops

Inequality comes in many forms. It is true of every race upon this

earth and is embedded in the life of all nations. There is this

continuous striving to be as equal as the other and this is where human

torment is best seen. In his latest collection of poems, inequality

(simple letters, please), Daya makes inequality his theme.

As you will recall, Daya took the 1998 State Literary Award for his

book kat bitha a story of Sigiriya and the mirror wall. He then broke

new ground with his first Asian e-novel, the saadhu testament that was

published as saadhu.com by Godage and Brothers in 1999.

After that he gave us the healer and the drug pusher in 2000 and

three more e-novels: the bastard goddess (2003); vessan novu vedun in

Sinhala in 2003; and thirst (2004).

In inequality and let me tell you that Daya deplores capital letters:

he is, one supposes neither capitalistic nor capitalised - he offers us

a collection he had written over 40 years, and, as he says, they arose

from an "insatiable itch for scribbling".

I suppose we writers do this all the time. Just yesterday, something

simply floated into my head and I scribbled it down. Then, looking at

it, I grinned, I had written: "If Martians are little green men, this

country seems to be full of them. "You see what I mean? Truly is

literature an all-sorts kind of thing and it is the mind that makes

things happen.

Daya's theme is inequality, and we, as a people, know so much about

it in this island we say is just 40 leagues from Paradise. Indeed, Daya

starts the ball rolling with his first three-liner, "inequality" (p 6)

inequality

breeds

inequality

Hungry villagers

And no, this is not what some may think is a pretty mundane

observation. What else can come out of inequality than greater

inequality? That first splintering leads to many more until, in the end

we have a land divided, communities divided, houses divided, families

divided, all hope strewn to the winds.

But what Daya has done is bring us close to the inequalities we seem

to accept or pass over as things of little consequence. This is starkly

presented in "food for thought" (p 12), where he tells us, remorselessly

enough, of the hungry villagers who live in pools of the sweat and blood

of their children in order to keep safe those who consider themselves

more equal that are:

the face of a starving child

stares at me from each grain of rice

on my plate all the food on my plate

grew on soil fertilized by the bodies

of those who sacrificed

their lives to keep us alive

The symbolism here is not that our farmers die of want. Instead they

waste away, moaning their sons plucked away from their homes, told by a

state to go out and die in battle; sons who are then brought back to lie

in their village graves, fertilize the soil.

Where is equality when one man can tell another to go out and die

that he might live? Today, certain politicians demand this sacrifice,

this massacre of the innocent, while their own sons haunt night clubs

like the arrogant monsters they are. Why were they not set to fight and

die? Ah, but you see, they are a breed more equal than that must become

T. 56 fodder, are they not?

There is so much inequality mirrored in this slim book. The village

boy in ragged shorts will call an old polythene bag his kite, and run

along the road, trying to get it to catch the breeze. But, as we know,

the children of the rich will descend on Galle Face Green with their

kites of many forms and colours, some brought in from Japan, Korea,

Thailand and Singapore.

There will be much fun and laughter, for this is a "Kite Festival".

Will there be a place on the green for the village boy and his rude

polythene bag? This poem kite (p. 14) is an eye opener and it was first

published in "Poetry International", Oregon State University, USA. What

makes the reader cringe is the gap - that huge gap that keeps widening

between the haves and have-nots. Who can ever claim equality?

In shelter (p. 17), we again see how well the inequality is marked -

the father, comforting his child, telling of a future dream-time that

can scarcely be imagined:

the tree canopy

is good enough shelter for us

from the sun and the rain

that's all I can give

yet I will send you to school

as long as I can someday

you too could build a mansion like that

for yourself and your children

Of course, this sense, this recognition of inequality is the kernel

of village grief as well, it is too bad that our rulers don't see this

as the sort of "gam peraliya" that brings all the old and serene ways

crashing down. The strong feeling of inequality pushes the young to

destroy the simple hopes and dreams of their parents.

This is a disquietude that takes hold of so many. In "inheritance"

(p. 23), we are told of the son who disowned his father, ashamed of the

loin cloth and the toiling in the rice fields. He wanted to equal the

city friends he had cultivated. Soon, he accumulates his own wealth,

immersed in the evil of the city ... but:

his elder son

disowned him

when he found

how his father had

amassed his filthy lucre

the younger son

threw his father out

once he took control

of the business

One son ashamed of his father, the other bursting with greed ... what

will the father now do? Return to the loin cloth and the rice fields?

His quest for equality ruined him and destroyed his dignity.

Again, sleep (p. 24) carries much of the same theme, but there lies a

world of difference. A villager will toil in the fields, return to his

hut to eat a plain rotti and drink a mug of tea; but he will sleep with

a faint smile on his face, his slumber deep and untroubled.

He has done his work for the day and the night holds no fears. But in

the cities are those who think themselves better, richer, more

worldly-wise; people he can never be. They exist in their status, their

money in the bank, in position and in power. Yet, the villager sleeps

and the inequality of it all does not really matter. Contentment is all:

he doesn't have

to worry

about

diet

cholesterol

blood sugar

ad doesn't need

sleeping pills

air-conditioning

and a featherbed

Daya also seems to tell us that inequality, although a dirty word to

some, can also be a blessing in disguise. This depends, of course, on

mental and spiritual attitude, and this is brought to our ken in

distance (p. 25), where the poor man, walking in the hot sun, knows all

the joys of nature that meet his steps; and not the rich man who flashes

by in his speeding car.

For the man in the car, the journey is marked by the time he takes to

travel a thousand metres ... but for the man who walks with his burden

on his back -

birds are singing

flowers are in bloom

children are playing

lovers are embracing

a cool breeze is

blowing

from the distant hills

over a blue stream and

a green earth

Sense of freedom

This sense of freedom cannot be denied. And yet, the poor man will

consider the car that flashes past him with some envy, won't he? In this

way, this sense of inequality becomes more convoluted. We see this is

health food (p. 25). A village woman will sell her land, her buffaloes,

to send her son to Italy.

Now she has nothing and is yet so proud to receive what her son send

her - food supplements, calcium, vitamin-enriched milk powder ... and

did she barter he healthy village life so that her son could send her

factory food from abroad? Is this how she could be regarded in her

village as a woman of quality?

In barefeet (p. 27), we meet the rural man who tried to bridge the

divide. But he had taken his feet away from the good earth. He must wear

cotton socks and leather-soled shoes, walk on rich carpets and smooth

tiling.

He can no longer walk barefooted on the gravel road to the temple The

same is true of the city diner in dining out (p. 27) who can sit at a

restaurant table and check the prices on the menu. His meal depends on

what he can afford. His taste buds are not activated, nor are his

digestive juices.

Does he eat well or does he eat to show others that he is their equal

who can order a meal as good as theirs? But there sits the unequal man

under a kumbuk tree by the edge of a rice field, eating his "embula" and

curries off a banana leaf and with a sigh of deep content. Who eats

better?

In book fair (pp. 28-29) the question again arises. The young man

will save his money to go to a book fair, buy the books he is proud to

collect. Oh, he has so many books but he never seems to be satisfied;

then, as he makes his way home in the rain, he sees the image of parched

village fields, a dried-up river, starving farming families, even hungry

beggars in the street. Can he give them books to eat? Is his life a

wasteland of books he could never live long enough to read?

Many of the poems resound with this curse of inequality. We see it in

the Four Noble Truths (p.30) and playtime (p. 33). This poem tells us of

the spoilt rich brat who can smash the TV monitor because she is bored

with her TV game. Here roomful of toys give her no pleasure either: ...

but:

Kumari was cooking

a meal

for her home-made

rag doll

outside their little hut

waiting for her

mother's return

from the tea estate

to bake a rotti

for her dinner

We see inequality in luxury (p. 36), and teachings (p. 38) as well;

and while the collection carries other poems as well, I find what I have

scrolled down of greatest significance.

As a finale, Daya has also given us his own 21st century Sigiri

graffiti, beautifully presented, as Malini Govinnage says, "A poem is a

part of the spiritual wealth of a person who creates it,," Daya is, to

all intents, a reformer of sorts.

He hangs his thoughts on seething crosses and asks that we regard

them with our conscience. This collection also reminds us, gently, that

we are unequal, one to another, in one way or another. It is only

contentment that dispels this mind-demon.

Carl Muller

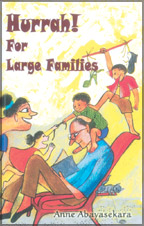

A book pulsating with vitality

Hurrah! For Large Families

Author: Anne Abayasekara

Vijitha Yapa Publications, 307 Pages, Price Rs.

499

In over six decades of avid reading I have rarely congratulated

myself so much on buying a book. The cover screamed temptation - Sybil

Wettasinghe's anarchic wit summarised everything about the carnival that

love and security can create in a blaze of colours; the trusting smile

of the bedazzled mother whose little savage surreptitiously plots her

downfall amidst the gang of tots, urchins and adolescents conveyed the

hilarious and occasionally horrific aspects of family togetherness.

It aptly mirrored the buoyancy and tough realism of the contents. To

lose yourself (or rather, find yourself) in the hook is not escapism.

"At a time of crisis in our country when nearly everyone is exclaiming

over the appalling escalation of crime and corruption" - is now

precisely the time for a saga as life-affirming, as sound, lively and

enjoyable as "hurrah for Large Families".

For the reflective, "Hurrah for Large Families by Anne Abayasekara

has a further dimension. The dates of each individual article coupled

with its contents are a piece of social history, revealing and thought

provoking.

As "a family counsellor over the past nearly 30 years", Anne is aware

of "scores of people who find little or no joy in marriage and family"

but she, like the majority of her readers, is more aware of their

rewarding aspects, and can indicate how these are increased and

safeguarded.

Sense, sanity, proportion, decency - who uses these words now? And

why not? "Hurrah for Large Families" makes us realise that despite all

that globalisation and our own politicians can do to us, there is still

areas where individuals can create an oasis for themselves.

How beautifully Anne writes! I find myself responding to a paragraph

on the noisiness of children as I might to opera - the orchestration is

so perfect. It is indeed, a mercy that such writing was not left as

silent newspaper articles, stacked up unread in the archives.

If, as Horace says, a writer is most successful who can give delight

while he instructs, Ms. Abayasekara is one such as she depicts seven

children and a delightful but not faultless husband: the portrayals

range from the richly funny when the lot are being fractious or

demanding to a touching appreciation of their thoughtfulness and

considerateness.

Every harassed mother of two or more can draw knowledge from her

experience. The book is particularly useful for young people bringing up

children now and fancying their woes are specific to this day and age to

discover that the very same problems confronted parents in what they

imagine were the serene 1960s.

Useful tips emerge: "A child who becomes stubborn when spoken to

angrily frequently responds to a kind but firm tone of voice. Requests

are generally complied with better than orders".

The book pulsates with a physical and mental vitality that

communicates itself to the reader and makes them alert to how intensely

pleasurable life is even without millions and how ecstasy is possible

without popping a pill. Family holidays and parties, nativity

performances at home with appealing or appalling performers,

mountaineering - it is a crowded and entertaining canvas.

And how many ideas are propagated! Planned child-free tete-a-tetes

for middle-aged couples., escapes from routine, even a rewarding tour

for senior citizens ("the children insisted we ask for wheelchairs".

The manner in which Anne Abayasekara's skilful communication of her

own response to the loveliness of landscape, the tug of responsibility,

the intimacy of a long marriage or interaction with the children mesh

with the readers concerns and feelings results in a very satisfying book

to read and to return to in the coming years.

Lakshmi de Silva

..................................

<< Artscope

Main Page |